Keagan Brewer

1 2015-09-18T16:31:00-07:00 Christopher Taylor // christopher.eric.taylor@gmail.com 946e2cf6115688379f338b70e5b6f6c039f8ba6f 5281 1 plain 2015-09-18T16:31:00-07:00 Christopher Taylor // christopher.eric.taylor@gmail.com 946e2cf6115688379f338b70e5b6f6c039f8ba6fThis page is referenced by:

-

1

media/Map_of_Angelino_Dulcert_cropped.jpg

2015-06-12T10:41:39-07:00

On the Arrival of the Patriarch of the Indians to Rome under Pope Calixtus II

55

image_header

2024-01-29T14:05:28-08:00

De Adventu patriarchae Indorum ad Urbem sub Calixto papa secundo (1122)

Long considered to be an origin point for the legend of Prester John, the anonymous De Adventu appears to be a compilation of lore about India, most notably borrowed from Gregory of Tours. The connection to the Prester John legend involves an anecdote concerning a man called Patriarch John who traveled from India to Rome (by way of Byzantium) in 1122. Reportedly discovered by papal legates in Byzantium, and having arrived for diplomatic reasons, this John had allegedly visited the Byzantine church to be formally recognized as "Patriarch of the Indies" (his predecessor had died).

Upon arriving in Rome to an audience with Pope Calixtus II (r. 1119-1124), Patriarch John described the marvelous land over which he ruled, including India's capital city of Hulna (unknown to geographers), where he resided and was protected by the largest walls in the world.

In addition, this text discusses he reputed miracles performed by the Apostle Thomas, including his magical floating tomb.

Although De Adventu does not invoke the name "Prester John" directly, its linking of a rich Christian patriarch of India and the figure of St. Thomas allows scholars to see it as one of the early, potentially direct influences on the Letter of Prester John. Uebel argues that this text directly influenced the Elyseus Narrative.

The text features descriptions that the Letter of Prester John would later echo, including an emphasis on the magnificent size of the capital city, the realms inclusion of a biblical river (Physon) full of precious gems, the punishment for non-believers in his realm, and the resting place of the Apostle Thomas.

That this anonymous account is corroborated by Odo of Rheims' "Letter to Count Thomas" makes the de Adventu all the more compelling as a potential source text for the Prester John legend.

Michael Uebel provides an English translation of one of the more interesting moments in the text:A short distance outside the walls of the city [Hulna] is a mountain, surrounded everywhere by the waters of the deepest lake, which extends in height out of the water, at the top of which stands the mother church of St. Thomas the Apostle… During the year the aforementioned mountain, where the church of St. Thomas is located, is not accessible to anyone, nor would anyone without cause dare to approach, but the patriarch who must go there in order to celebrate the sacred mysteries, and in the church people from everywhere are allowed entrance only once a year. 29. For, eight days before and after the approaching feast day, the level of the water surrounding the mountain so greatly diminishes that it is hard to tell there was any water there at all; from this place there, people from everywhere came together [to visit the sanctuary of St Thomas]

Zarncke created his edition of the text from nine manuscripts, one printing, one fragment, and from two chronicles which contained the tale (Brewer, 5)More on St. Thomas and medieval Christianity in India.Slessarev provides a useful overview of the text (pp. 9-11):“The first Western sources to record the miracles performed by St. Thomas and to announce the victory of Prester John over a Moslem army had one common characteristic… Both accounts contain legendary elements, and while in the case of St. Thomas such a background was regarded as more or less natural, Prester John has been almost exclusively viewed in a historical setting. Yet he too was at least partially clothed in the garb of legend, and the connections between the two traditions want examination."

“The anonymous author called the Indian prelate Patriarch John and let him travel for a year from his home country to Constantinople where he was to be confirmed in his position and invested with a pallium. Here in the imperial city he became acquainted with papal envoys who had come from Rome to negotiate an end to the unfortunate split between the Greek and Roman churches… the Patriarch begged the papal emissaries to take him along on their return so that he might see Rome… and it was at a papal reception in the Lateran palace that the Indian dignitary told the story of St. Thomas’ miracle-working hand."

"The city over which he ruled… was the capital of India and its name was Hulna. In circumference it extended for four days’ journey and its walls were so thick that two Roman chariots set abreast could be driven on them. Through the middle of the city flowed the River Physon on its course from the earthly paradise. Its waters were crystal clear and they were full of gold and precious stones. Hulna’s population consisted exclusively of Christians among whom there were no heretics or unbelievers, because such persons either came to their senses or died."

Brewer's compilation of Prester John sources begins with de Adventu (pp. 30-38) and includes an English translation.

Read Latin text on Google Books (pp. 837-843) -

1

2015-06-12T10:55:17-07:00

The Two Cities, A Chronicle of Universal History

35

image_header

2024-01-17T11:37:51-08:00

De Duabus Civitatibus (1157-1158)

Inspired by civil unrest in Germany and written shortly after the fall of Edessa in 1143, Otto of Freising's Historia de duabus civitatibus has come to be known for providing an important early source on the figure of Prester John.

Oddly enough, this vital information is nothing more than an a recorded anecdote from 1145 that tells of a colleague of Otto's called Hugh of Jabala, a bishop from Lebanon, who was relaying news of a promising Nestorian Christian prince, Iohannes. This news as given in the presence of Pope Eugenius III at Viterbo.

According to Otto, widely reputed to be a trustworthy historian, this Iohannes, hailing from the distant East of the Magi, had recently conquered Persia and headed West to assist crusaders in their defense of the Holy Land. Unfortunately, Otto relates, a flooded Tigris River prevented him from aiding his Latin Christian brethren. As summarized by Slessarev (27-28):He [i.e. Hugh] related also that not many years before a certain John, a king and priest who dwells beyond Persia and Armenia in the uttermost East and, with all his people, is a Christian but a Nestorian, made war on the brother kings of Persians and Medes, called Samiardi, and stormed Ekbatana (the seat of their kingdom).

When the aforesaid kings met him with an army composed of Persians, Medes and Assyrians a battle ensued which lasted for three days, since both parties were willing to die rather than turn in flight. Prester John, for so they are accustomed to call him... emerged victorious.

He said that after this victory the aforesaid John moved his army to the aid of the Church in Jerusalem. But that when he had reached the river Tigris and was unable to transport his army across that river by any evidence he turned towards the north... tarried there for several years... [and] was forced to return home.”

In analyzing the anecdote that arguably sparked the Prester John fever across Europe, Niayesh (p. 157) notes the structural "ambivalence" of Hugh's account, noting that his story was "caught half-way between the pagan past of classical authorities and the present of Christian Crusaders" insofar as Prester John is "made to fight the long extinct nations of the Medes and Assyrians, rather than directly facing contemporary 'Saracens.'

Even the somewhat contemporaneous historical details do not, in actuality, herald a Christian savior of western Europe. Although this rumor spawned the centuries-long belief in an Eastern potentate capable of uniting Christendom, the initial account of an Eastern anti-Islamic leader was later understood to refer to the deeds of the Qara Khitai, a nomadic Chinese tribe descending from Manchuria. Significantly, this battle took place in Samarkand, not Ecbatana, as Hugh reports.

Nevertheless, despite historical mistranslation and Iohannes's failure to reach even Byzantium, this rumor helped set in motion, for many Europeans, a belated recognition of the world beyond the Tigris.

Brewer edits and translates the relevant passages of the chronicle (pp. 43-45). -

1

media/Map_of_Angelino_Dulcert_cropped.jpg

media/Screen Shot 2021-07-25 at 5.11.20 PM.png

2015-06-12T10:50:54-07:00

Letter to "Count Thomas" on a certain Miracle of St. Thomas the Apostle

26

image_header

2023-12-01T09:32:55-08:00

Domni Oddonis Abbatis S. Remigii Epistola ad Thomam comitem de quodam miraculo S. Thomae Apostoli (1122)

This letter, penned by Odo of Rheims, describes the arrival to Rome of a Byzantine retinue escorting a nameless Indian Archbishop who described to an audience including Pope Calixtus II the marvels that occur in his country through the ghostly power of St. Thomas. Odo claims to have witnessed this meeting.

From Silverberg (p. 32):

The events in this text largely mirror those described in the de Adventu, with some key differences. For one, Odo claims that Patriarch John arrived with a Byzantine retinue while the de Adventu asserts that John arrived with a group of returning papal legates. In another example, Odo records that it is a river that prevents access to the mountain that houses the magical shrine of St. Thomas, rather than the lake de Adventu suggests. Though a minor discrepancy, the motif of rivers is bountiful in Prester John lore.“Odo, who lived from 1118 and 1151, probably wrote the letter between 1126 and 1135. In it he tells of being present at the court of the Pope when a delegation of ambassadors form Byzantium arrived, bringing with them a certain Archbishop of India, whom Odo does not name… He declares that the ruler of the archbishop’s country had died, leaving no heir, and the archbishop had gone to Byzantium to obtain a new prince for his land from among the Byzantine emperor’s entourage. Twice the monarch had received the archbishop graciously and had nominated one of his courtiers to the Indian throne, but each time the designated candidate had perished en route to India. The emperor had declined to select a third; but instead of setting out immediately for his homeland, the archbishop had gained permission to visit Rome in the company of the Byzantine ambassadors… Odo relates that the Pope and his cardinals refused to believe these tales until the archbishop swore an oath that convinced them”

From Slessarev (p. 12):“The greatest deviation from De adventu occurs, however, in the explanation of the causes of the Patriarch’s trip to Constantinople. According to Odo, the prince of the country, friendly helper of the archbishop, had suddenly died. This misfortune compelled the prelate to go to the emperor at Byzantium and beg him for another prince. The Greek monarch received him graciously and provided him twice with a suitable candidate from his immediate entourage, but in both cases, for no reason stated, the courtiers died while en route to India.”For original Latin text, see Zarncke's edition. Read Latin text on Google Books (pp. 843-845)

For an English translation, see Brewer (pp. 41-42).More on St. Thomas and medieval Christianity in India. -

1

media/parzival.png

2015-06-12T11:01:35-07:00

Parzival

25

image_header

2024-01-08T14:56:59-08:00

Parzival (1197-1215)

Written in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival offers readers the most elaborate medieval presentation of the Grail legend of the time. Framed as something of a rejoinder to Chrétien de Troyes’s incomplete Perceval, Wolfram’s narrative follows an enigmatic (likely invented) source, Kyot, through whom the reader is granted access to the “heathen” Arabic material essential to the story of the Grail that was absent in Chrétien's tale.

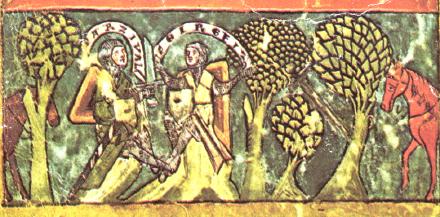

Among Wolfram’s inventions to the narrative is the inclusion of Feirefiz the pagan half-brother to Parzival, an equal in knightly virtue and ability and distinguished primarily by his mottled black and white skin. Feirefiz, who falls in love with the Grail’s maiden, Repanse de Schoye, decides to accept baptism in order to be closer to his love, an act that also allows him to see the Grail. Soon after, Parzival decides to pass the Grail onto Feirefiz, who marries the Grail maiden, returns to the East to preach Christianity, and gives birth to a son, the future keeper of the Grail. That son is Prester John, whose name thereafter becomes the official title of Indian kings. The story of this Prester John is continued in Albrecht von Scharfenberg's sequel/prequel Der jüngere Titurel. Parzival and Feirefiz (MS Cgm 19, folio 49v, State Library, Munich)Wolfram writes (pp. 344-45):

Parzival and Feirefiz (MS Cgm 19, folio 49v, State Library, Munich)Wolfram writes (pp. 344-45):[Repanse de Schoye] gave birth… in India, to a son, who was called Johan. Prester John they called him; forever they retained that name for the kings there. Feirefiz had letters sent all over the land of India, telling them about the Christian way of life.

In Parzival, Wolfram not only incorporates Prester John into Arthurian lore, he consequently builds John into English history. Prester John becomes a distant descendent of Parzival, himself a distant descendent of Arthur, and yet Wolfram also maintains John’s uncanny, hybrid status in the minds of his readers. As the son of the mottled Feirefiz, Wolfram’s Prester John is himself marked, genealogically and physically, as simultaneously European and Other. Yet while the text integrates John into the Matter of England, Parzival makes no explicit reference to the legend of Prester John. Rather than accrete onto what is already a dense historical tradition, Wolfram connects the two worlds, un-knowing the Prester John legend in order to begin a tradition that might better amplify John’s relevance to Wolfram’s audience.

Brewer sees Parzival as a transition point for the legend (p.22):Prester John plays a minor role in the story, appearing as a man, the son of the grail maiden Repanse and the half-Saracen Feirefiz, but a man whose name subsequently became the title for a line of kings descended from the original man named Prester John. Although Parzival is a fictional text, this remark represents a conceptual transition in the understanding of 'Prester John.' While earlier writers thought of Prester John as a single man and later writers thought of Prester John as a title, Wolfram von Eschenbach saw him as encapsulating both.Read Jessie L. Wetson’s 1912 English translation of Parzival: -

1

media/H1042-L71503402.jpg

media/new_presterjohnlogo.jpg

2015-07-28T18:55:42-07:00

Path Five: 1521-1699 AD

25

image_header

879654

2023-12-17T10:10:59-08:00

Prester John and European Modernity

This period of the legend begins with the earnest (and arguably successful) search by a Portuguese Embassy in 1520 to locate Prester John in Ethiopia, features minor appearances in literary texts (many of which reflect the neo-Chivalric revival of the late 1580s through the 1590s), and terminates in an age of skepticism about the legend that closes the 18th century.

During this era, Prester John was mainly identified with Africa-- particularly Ethiopia. Through the sixteenth century, this identification became common for most European world maps. On a 1540 map by Munster, for example, the capital city of the kingdom of Prester John is situated in "Hamarich" (may be present day Hamar).

As Niayesh argues (p. 164), here we see a transformation of the figure of Prester John from belated European savior "into the prototype of the eastern ruler who is to be overcome and no longer sought after as an ally." While Niayesh's comment accurately describes the developments of some of the writing on Prester John (especially in fiction), his kingdom remained for others still a real physical target (or at least a useful rhetorical ally).

Given Portugal's aggressive missions to Africa in general and Ethiopia in particular, the era is dominated by Portuguese thought and writing, but other European countries were still using the figure of Prester John as a means of negotiating their own power and understanding of the world. Several English writers, including George Abbot, found a spiritual ally in Prester John by emphasizing the imaginary rulers resistance to Catholicism. Others, such as Edward Webbe, continued to promote the same story that had been told since Mandeville.

It can be argued that this era ended in the year 1633, when Ethiopia closes its borders to Europeans after the expulsions of the Jesuits by Emperor Fasilides, yet, as Brewer (p. 273) points out, there are hundreds (if not thousands) of texts from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries that contain some comment associating Prester John with Ethiopia.

While European travel to Ethiopia may have ended in the first half of the seventeenth century, the texts and tales that circulated for the rest of the century almost entirely reflect the narratives that first established this era, most due to Portuguese travel. -

1

media/Map_of_Angelino_Dulcert_cropped.jpg

2015-06-12T11:03:40-07:00

History of the Deeds of David, King of the Indies

23

image_header

2023-12-31T09:44:37-08:00

Historia Gestorum David regis Indorum // Relatio de Davide (1220)

Brewer (p. 107) usefully describes the muddled story behind this text supposedly derived from an Arabic source, but popularized in the West by Jacques de Vitry:

The text itself attests to how this King David had attacked the King of Persia and conquered several cities along the Asian Steppe, including Bukhara, Samarkand, Khurasan, and Ghazna.This confused text is a Latin translation of what is thought to be a tract originally written in Arabic by a Christian in Baghdad in 1220-21, but some of the material here was certainly added by its Latin translators. It describes in essence the conquests of Chingis Khan, but instead he is presented as a Christian king named David, great grandson of Prester John, a figure who becomes from this point on a regular feature of the Prester John legend... [A]lthough the text does display some intimate knowledge of the initial movements of the Mongols, the details became so distorted by the time they reached the crusaders that those initial facts became grossly misunderstood.

In the first version of the text, King David is identified as "the son of King Israel, the son of King Sarkis, the son of King John, the son of Bulgaboga" (qtd. in Brewer, p. 107). Importantly, King David is not linked to Prester John until the third and final version of the Relatio de Davide begins to circulate.

Silverberg (p. 71) summarizes:This King David was a Christian, the bishop reported, and was either the son or the grandson of Prester John—although, Bishop Jacques pointed out, “King David was himself commonly called Prester John.” His kingdom was deep in Asia. His involvement in the affair of the Near East had come about because the Caliph of Baghdad had been threatened with war by a fellow Moslem prince, the Shah of Khwarizm; seeing no other ally at hand, the caliph had requested the Nestorian Catholicos—or Patriarch—of Baghdad to summon King David to his aid, and the king had agreed to defend the caliph against the Khwarizmians” (71).

In addition to fueling belief in the kingdom of Prester John, this text had a huge impact on the outcome of the Fifth Crusade. Jacques de Vitry, preacher and crusade propagandist, reaches shared the information contained within the text with crusaders in Damietta. The text promises the dissolution of Islam at a time when King David joins forces with a king in the west. Jacques has the report translated immediately. He then sends letters containing parts of this text to Pope Honorius, King Henry III of England, Duke Leopold of Austria, and to several academics at the University of Paris. Spirits lift within and without the crusader camp, essentially renewing the hope for a Christian recovery of Jerusalem. Buoyed by prophecy and heedless of local conditions, the crusaders at Damietta decide to invade Cairo immediately to fulfill the prophecy, rejecting an agreement with the Sultan Al-Kamil that would have given Jerusalem back to the crusaders in exchange for Damietta. The Nile rises, turning the invasion of Cairo into defeat. The armies of the Fifth Crusade surrender to the Sultan of Egypt, Al-Kamil, Saladin’s nephew, a few weeks later.

Brewer (101-125) collects three versions of this text, all of which tell of a King David prophecied to help the west defeat Islam.For more on the historical reality animating the Relatio, see Richard.

For a close account of the entire Fifth Crusade, see Powell. -

1

media/Screen Shot 2015-12-12 at 6.41.57 PM.png

2015-07-30T04:00:08-07:00

Trauailes of Edward Webbe

19

image_header

2023-12-20T19:31:56-08:00

Edward Webbe, Chief Master Gunner, His Trauailes (1590)

Original Title: The Rare & most wonderful thinges which Edward Webbe an Englishman borne hath seene & passed in his troublesome travailes in the Citties of Jerusalem, Dammasko, Bethelem & Gallely; and in the Landes of Jewrie, Egipt, Grecia, Russia, & in the Land of Prester John. Wherein is set foorth his extreame slaverie sustained many yeres togither, in the Gallies & wars of the great Turk against the Landes of Persia, Tartaria, Spaine, and Portugall, with the manner of his releasement, and comming into Englande in May last. London. Printed by Ralph Blower, for Thomas Pavier

In this embellished travel account Edward Webbe describes, among other eastern sights, the Christian land of Prester John. Webbe's account bears a close resemblance to that of Mandeville. It was so popular that in its first year (1590) it went through three separate publications in England.

Even as Portuguese missionaries had repeatedly visited Ethiopia and claimed to meet with Prester John, now the mortal king of that land, writers such as Webbe was delighting readers simply by revisiting the tropes of the Letter of Prester John.

Even as late as 1590, the popularity of the original Prester John myth seemed to enduring, even considering the dozens of circulating texts that identified Prester John as the fallible monarch of Ethiopia. Webbe's book found three publishers in 1590 alone.

Still, as Silverberg (p. 316) points out, the book had its detractors. Richard Hakluyt leaves Webbe's story conspicuously absent in his three-volume collection of significant European voyages in 1598, and Samuel Purchas castigates Webbe as "a mere fabler" in 1625.

In terms of the book's relation to the Prester John legend, Edel Sample relates,[I]t is clear that Webbe relishes the task of describing the magnificence of Prester John’s court and the strange sights in his country. Webbe writes of the customs, political relations, and strange creatures that he witnessed. Three woodcuts are included; the first depicts a bearded “wilde man”, and we learn that one of these men can be found in Prester John’s court and another can be found in Constantinople. The text explains that this savage man is a public spectacle; chained by the neck, he is covered in hair, wears a mantle, and eats the flesh of condemned criminals. The other two woodcuts show a unicorn rampant and an elephant (“three score and seventeen Unicornes and Oliphants” live as tame pets in a park of Prester John’s.) Other texts on Asia and the Middle East may have influenced Webbe’s account of this ruler and his exotic land. For instance, his account of the sixty kings that daily serve Prester John is reminiscent of the multiple tributary kings that serve Bajazeth and Tamburlaine in Marlowe’s play (c.1587); the use of skulls as culinary utensils appears in Solinus’s Polyhistor (1584); while accounts of strange beasts, ‘wild men’, and cannibals were not uncommon and appear in Solinus and in Pliny (1585).

Webbe identifies Prester John’s kingdom with the traditional worldly Paradise, following Mandeville almost completely. However, it can also be surmised that theTravels bears some relation to the Russian theories about Prester John that circulated among the Old Believers, who claimed that Prester John's land was a haven for religious dissenters.

Brewer (pp. 230-31) excerpts the relevant section on the land of Prester John.

Read the full Travailes online.

Read more about Webbe and his Travels. -

1

2015-05-21T11:48:30-07:00

Early Literary and Political Reverberations

16

Wolfram through the Fifth Crusade

plain

2021-09-08T10:47:57-07:00

In the half-century that followed the appearance of the letter, interest in Prester John increased steadily, most visibly through the transmission and translation of the Letter, which was translated into the vernacular by the end of the twelfth century.

Several chronicles composed before 1200, including Geoffrey of Breuil's Chronica, Roger of Howden's Gesta Regis Henrici II et Ricardi I, and Annales Colonienses Maximi, along with other "historical" texts such as Gerald of Wales' De Vita Galfridi contain some mention of either the figure or letter of Prester John, suggesting that this text was quickly transmitted and taken literally.

This is not the say that the Letter's early readers understood the figure of Prester John the same way. While Geoffrey of Breuil comments that Prester John was given his name due to his humility, Gerald of Wales relates an argument in which one party was accused of being "so prideful and arrogant he was like Prester John" (Brewer, 274). Even from its beginnings, it seems, this legend meant everything to everyone.

This first wave of popularity evidently reached Pope Alexander III, who crafted a reply to the eastern priest-king. Evidently, Pope Alexander sent his personal physician, Master Phillip, as envoy to seek Prester John's kingdom and to deliver this reply, which urged John's instruction in Catholicism. We never hear back from Master Phillip.While Alexander’s letter is typically read at face-value, it also has the effect of re-inscribing ecclesiastical power, in the form of doctrinal Catholicism, as the most important feature of any imperial project. Hamilton reads the letter as a kind of public rhetorical performance, a stance he supports by noting that Alexander made several copies of his letter.

This rhetorical reflexivity became a trademark feature found in a number of adaptations of the legend Wolfram von Eschenbach provides the first fully literary account of Prester John when he integrates the legendary ruler into the genealogy of Arthurian romance.Among the early adaptations of the legend, the most impactful was John's role as prophesied savior for the Fifth Crusade. Although the legend was birthed through a letter addressed to Western rulers written between the Second and Third Crusades, there were no attempts to invoke John during the third or fourth crusades.

During the Fifth Crusade, Prester John returns. The figure of Prester John becomes entangled with that of a figure called "King David" and the epistolary genre that birthed the legend gives way to the genre of prophecy. Leaders of the crusade, including Jacques of Vitry, predict the arrival of a Prester John figure who would help defeat Islam once and for all. These prophecies found their way into several chronicles before and after the Crusade, the pertinent details of which are recorded on the following pages.

Of course, Prester John did not arrive, and the Europeans ceded their advantage and were summarily defeated. The disastrous end to the Fifth Crusade illustrates the imprint the legend of Prester John had made on Europe, even within the first fifty years of the letter's circulation.

The following two pages provide a visualization of this early spread of the legend. -

1

2015-06-18T14:51:23-07:00

History of the Three Kings

16

image_header

2024-01-12T18:11:52-08:00

Historia Trium Regum (b. 1375)

John of Hildesheim's Historia Trium Regum links Prester John, St. Thomas, and the Three Magi in a single text for the first time. It was originally written in Latin– though no extant copies survive. There exists an early English translation from which Brewer excerpts the relevant Prester John material

As Hamilton (p. 181, n. 63) notes, Hildesheim "claimed to have based his work on French translations made at Acre of 'caldayce et hebrayce scriptos' brought there from India." Hamilton also mentions that Hildesheim likely consulted the collected writings concerning the Magi housed in Cologne's cathedral. Numerous manuscripts containing the English translation survive, the earliest which date to the first half of the fifteenth century.

The dating of the original text is difficult, especially because its authorship was ascribed to John of Hildesheim a century after his death by Johannes Trithemius (1462-1516). Hamilton refers to the text as an early thirteenth century text, but it seems safer to date the text as written before the death of John of Hildesheim, which occurred in 1375.

The Historia Trium Regum provides a cohesive story that links the historical Magi with the current political reality in Europe, which includes the legend of Prester John. Hildesheim based his story on the Gospel accounts of the three kings as well as the apocryphal commentary on Matthew known as the Opus Imperfectum (5th century).

Some time after returning to the East after visiting the infant Christ, these kings (Melchior, Balthasar, and 'Jasper') are converted to Christianity by the Apostle Thomas, who served as the. When Thomas died, these Magi then selected an heir to serve as spiritual Patriarch of the Indies. They also elect a secular ruler to act as rex et sacerdos, and they call this leader "Priest John," so-called in reverence to John the Evangelist. In the narrative, Prester John, here called "Preter Johan" the secular ruler of India, rules in tandem with a “Patriarch Thomas":Than these thre kynges archebysshoppes and other bysshoppes of comyn [common] assent of all the people chose an other man that was dyscrete to be lord and gouerner of all the people in temporalte. And for this cause that yf ony [any] man wolde ryse or tempte agaynst the patryarke Thomas or agaynst that lawe of god yf so were that the patryarke myght not rule hym by the spyrytuall lawe, than sholde this lorde of temporall lawe chastyse hym by his power. So this lorde sholde not be called a kynge or emperour, but he sholde be called Preter Johan. And the cause is this. For the thre kynges were preestes and of theyr possessyons they made hym lorde. For there is no degree so hygh as preesthode is in all the worlde, nor so worthy. Also he is called Preter Johan in worshyp of saynt Johan the euangelyst [the evangelist] that was a preest the moost specyall chosen and loued of god almyghty. Whan all this was done these thre kynges assygned the patryarke Thomas and Preter Johan, that one to be chefe gouernour in spyrytualte, and that other to be chefe lorde in temporalte for euemlore. And so these same lordes and gouemours of Inde ben [are] called unto these dayes. (qtd. in Brewer, p. 209)

Thus Prester John becomes a title, an idea echoed in Parzival and Younger Titurel, and an idea that anticpates the Prester John as Dalai Lama narrative path.

The narrative also extrapolates on the Magi legends, which had circulated around Germany since the time of the original Prester John Letter.

It is also notable that Hildesheim refers to Prester John's son, King David, as an enemy to the Mongols.For more on the connection between the Prester John and Magi traditions, see Hamilton.

Read an early English translation online.

-

1

media/Map_of_Angelino_Dulcert_cropped.jpg

2015-06-12T11:00:17-07:00

Letter to Prester John

15

image_header

2024-01-27T19:32:59-08:00

Letter To Prester John (1177)

In 1177, Pope Alexander composed a letter to Prester John, "the illustrious and magnificent John King of the Indies," and sent Master Phillip, his personal physician, as envoy to petition for John’s instruction in Catholicism. We never hear back from Master Phillip. While Alexander’s letter is typically read at face-value as a genuine attempt to reach out to an eastern Christian priest-king, it also has the effect of re-inscribing ecclesiastical power, in that Alexander establishes himself as the custodian of doctrinal Catholicism, the adherence to which should be considered the most important feature of any imperial project.Brewer (pp. 94-6) provides an English translation of Alexander's letter. Although most critics understand this letter as a response to the Letter of Prester John, Brewer maintains "that is emphatically not the case." He sees the letter instead as a "curious anomaly."For the Latin text of the letter, see Zarncke. Read Latin version online at Google Books (pp. 935-946).Bernard Hamilton reads the letter as a kind of public rhetorical performance, a stance he supports by noting that Alexander made several copies of his letter (184). Although scholars, including Hamilton, have tried to explain the legend as a hoax perpetuated by Frederick’s inner circle that spiraled out of control, this explanation fails to account for the survival of the legend beyond the political intrigues of the twelfth century.From Hamilton, "Prester John and the Three Kings of Cologne":“[T]he aim of the author of this letter is to show that Frederick’s concept of church-state relations, unlike that of Alexander III, produced harmony in the Christian world, and enabled Christians to unite against the enemies of the faith” (180).

“That Alexander III took the letter seriously is evident from the reply which he wrote to it from Venice on 27 September 1177. Significantly he omits the title ‘Priest’ and addresses John as ‘illustrious and magnificent king of the Indies.’ Alexander states uncompromisingly that he is the head of the church on earth, and then explains his reasons for writing. Philip, his physician, had been sent on a mission to John and had met some of his subjects who, he discovered, held heretical opinions about some points of doctrine. They had asked to be given a church in Rome and an altar at the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, to which their clergy might come to be instructed in the Catholic faith. The pope is therefore sending Philip back to John to give him Catholic instruction and to discover what his true wishes are” (183).

“It is often supposed that this letter gives a factual account of Alexander III’s attempts to make contact with Prester John… It is, however, possible that the pope’s letter was written for a quite different reason. When Prester John’s letter began to circulate Alexander III was on excellent terms with Manuel Comnenus and would have been able to verify that he had not sent the letter to Frederick I. He may therefore have inferred, just as modern scholars have done, that it was a western forgery. It clearly originated in Barbarossa’s circle and implicitly defended the kind of Christian society which the emperor was trying to implement. The timing of the pope’s reply is significant: he waited for twelve years after the publication of the letter until the Peace of Venice had been concluded… On 27 September, after the practical details of the Peace had been arranged, Alexander wrote to Prester John, emphasizing that the emperor of the Indies… had now agreed to be instructed in the truths of the Catholic religion by the only competent authority, St. Peter’s vicar. Arguably this letter was not written to an eastern Christian prince whom the pope had wrongly identified as Prester John, but to the faithful west who had read and been misled by Prester John’s letter” (183).Nicholas Jubber, eight hundred years later, attempts to re-trace the emissary’s route and deliver Alexander’s reply (despite the obvious facts standing in the way of this feat). -

1

2015-06-15T15:09:17-07:00

The Travels of Marco Polo

15

image_header

2023-12-29T16:38:32-08:00

Devisement du monde (c. 1298)

The Devisement (or Livres des merveilles du monde) remains one of the most well-known narratives to survive the Middle Ages. Dictated by an imprisoned Marco Polo to fellow inmate and veteran romancer Rustichello da Pisa, the book records– and sometimes embellishes– the travels of Polo (along with his father and uncle) to the court of Kublai Khan in the late-thirteenth century.

Although written in French, the text was quickly translated into Italian and Latin. More than one hundred manuscripts survive, each slightly different from the others. The Travels became a medieval best seller, even though the imaginative flourishes of copyists makes it difficult to determine what the original text might have looked like.

Marco Polo's Travels features the figure of Prester John in a number of chapters (64-68, 74, 109-110, 139, 200). Polo, following the Dominican missionaries that visited the Mongol Empire before him, relates a tale of Prester John that demystifies the legendary qualities of the letter all the while testifying to the historical existence of an eastern Christian prince.

For Marco Polo, Prester John (or Un-khan) was a powerful prince who ruled over the Tartars (Mongols), but was overthrown, in a battle Polo himself describes, by Genghis/Chinggis Khan. Later, in the mid-14th century, the imaginary travels of Sir John Mandeville will crib from Polo's now-canonical observations about the east.

Silverberg (p. 132) puts Marco Polo's reduction of the Prester John legend succinctly:For Marco, Prester John was a khan of the steppes, and he was dead, and his descendent of the sixth generation, King George, ruled the insignificant principality of Tenduc as Kublai Khan's vassal.

Even if Polo's narrative demystified the legend of Prester John, its romance narrative style, combined with its fascinating insights, some of which related tangentially to the Prester John legend (including visiting the shrine of St. Thomas), did not ultimately do much to diminish European interest in Prester John.

Background on Polo’s expedition.See Polo’s route.

Brewer edits and translates the Prester John portions of Polo's travels (pp. 171-188).

Silverberg excerpts the three mentions of Prester John in the Travels.

More on the travels and their veracity. -

1

media/cron1.jpg

2015-06-15T15:09:07-07:00

Chronicon Syriacum

15

image_header

2021-07-17T14:30:40-07:00

Makhtbhanuth Zabhne (c. 1258-1286)

Bar-Hebraeus's Chronicle, written in Syriac, aspires to narrate world history from Creation until the current day, in two books (concerning secular and sacred history, respectively).

In the Chronicon Syriacum, which concerns civil and political history, Bar-Hebraeus records an occurrence in the early eleventh century that connects to the legend of Prester John. According to the Chronicon the Mongol Keraits of the East Steppe adopted Nestorian Christianity in 1007. This is significant insofar as the early European legends speaking of a powerful Indian prince John cast this figure too as Nestorian and it was not known at that time whether or not Nestorian Christianity had spread that far east.

Bar-Hebraeus then goes on to mention that it was a King David who, as chief of these same Keraits, was defeated in 1202 by Genghis Khan, who was once King John's vassal. The Syriac documentation of this events matches those of western authors, including the narrative of Marco Polo's journey. There, however, King David/Prester John is known as Ong Khan.From Silverberg:

How are we to account for William’s [of Rubruck] linking of Togrul and Kuchluk the Naiman (‘King or Presbyter John’)? They were in fact not brothers, nor of the same tribe, nor of the same generation, nor could Togril, who died in 1203, possibly have succeeded to the throne of Kuchluk, who outlived him by sixteen years. A clue to the source of his error can be found in the Chronicon Syriacum of the Syrian cleric Gregory Abulfaraj Bar-Hebraeus, who lived from 1226 to 1286: speaking of the conversion of the Keraits to Christianity, he notes that in the time of the Mongol dominion they were ruled by an ‘Ung Khan who is called Malik Yuhanna,’ that is, ‘King John.’

See Brewer (pp. 169-170) for the English translation of the account of Prester John in the Chronicon. -

1

media/Nuernberg_schedel.jpeg

2015-07-29T17:17:19-07:00

Nuremberg Chronicle

13

image_header

2024-01-14T10:55:12-08:00

Published in Nuremberg in 1493, composed in Latin, and later translated into German, Hartmann Schedel's Chronicle (sometimes known in English as Schedel's World Chronicle) was commissioned by Sebald Schreyer (1446–1520) and Sebastian Kammermeister (1446–1503). The text is an illustrated universal chronicle that reflects Europe's understanding of the wider fifteenth century world. It remains untranslated into English.

Schedel touches briefly on Prester John, locating the legend's beginnings in the Letter of Prester John and, as Brewer (p. 286) suggests, the De Adventu as well. Following earlier Portuguese material related to the myth of Dom Pedro (notably the anonymous Travels of Infante Dom Pedro of Portugal and Santisteban's Book of Dom Pedro), Schedel locates Prester John in Cathay (China).

The text also contains a woodcut of a very European Prester John.

-

1

2015-07-22T17:11:42-07:00

Travels of William of Rubruck

13

image_header

2023-12-31T13:00:53-08:00

Itinerarium fratris Willielmi de Rubruquis de ordine fratrum Minorum, Galli, Anno gratia 1253 ad partes Orientales (c. 1253-1255)

William of Rubruck's Itinerarium records the Franciscan missionary's quest, ordered by King Louis IX, to convert the Tatars to Christianity and to gauge their potential as crusading allies.

Like John of Plano Carpini's Ystoria Mongalorum, William's Itinerarium records basic observations about the geography, culture, religion, and daily life of the Mongols. William's account has been more historically useful due to his incisive observations and his clear writing style. As Brewer (p. 162) notes, William was the first European to cast doubt on the veracity of the Prester John legends, though he does buy into Prester John's historical reality.

In Chapter 17 William writes of a powerful Naiman (Nestorian) shepherd who rose to power as King John at the beginning of the twelfth century during the power vacuum created by the death of the "Gürkhan." William is careful to note that the rumors that began to spread about this King John are exaggerations.

From Dawson’s English translation (122-23):

[...]In a certain plain among these pasture lands [of the Carcathayans] was a Nestorian, a mighty shepherd and lord of all the people called Naimans, who were Nestorian Christians. On the death of Coir Chan, this Nestorian set himself as king and the Nestorians called him King John, and they used to tell of him ten times more than the truth. For the Nestorians coming from these parts do this kind of thing-- out of nothing they make a great rumour… I passed through his pasture lands and nobody knew anything about him with the exception of a few Nestorians.

This John had a brother by the name of Unc, like him a mighty shepard, and he was beyond the pastures of these Carcathayans, separated from his brother by a distance of three weeks’ journey, and he was lord of a little town called Caracorum,... King John died without an heir and his brother Unc grew rich and had himself called Chan and used to send his herds and flocks as far as the Mongol boundaries… And the Tartars and Mongols made him their leader and captain.”

See also this useful online article on William and his travels.More on William of Rubruck.

-

1

media/Screen Shot 2021-05-31 at 12.50.22 PM.png

2021-05-31T11:45:42-07:00

Tom a Lincoln

13

image_header

2022-03-01T13:46:19-08:00

Two texts from the early seventeenth century use the title and figure called Tom a Lincoln. The first, The Most Pleasant History of Tom a Lincoln, an unremarkable chivalric romance written by Richard Johnson around 1607, relates the adventures of Tom and his fellow Knights of the Round Table. The second, a shorter dramatized version tentatively attributed to Thomas Heywood and written somewhat later than the prose romance is simply called Tom a Lincoln and follows much of the same basic romance plot. Interestingly, both texts feature a scene with Prester John. In the play, Tom and his fellow knights reach the realm of Prester John. After Tom defeats a dragon, Prester John refuses to allow his daughter Anglitora to marry Tom, and the two abscond together, leaving John and his grieving queen Bellamy to commit suicide.

A Niayesh (p. 55) points out, in the play Prester John has become emptied of any of the significations that marked his identity for the previous five centuries:

Brewer (p. 233) includes an excerpt from a 1631 prose edition of Tom a Lincoln, published in London.Nothing in the play lends any specificity to his realm, where the character and his daughter simply appear as types of the angry father and disobedient daughter. No reference is made here to Prester John's being a Christian; in fact, he actually swears by 'the gods' (l. 2529) like a true pagan. The geographical whereabouts of his land are in no way detailed, leaving us only to infer that he is neither Indian... nor Ethiopian.

Read the full prose version at the Camelot Project. -

1

media/Map_of_Angelino_Dulcert_cropped.jpg

2018-01-08T11:34:36-08:00

Jacques de Vitry's Letter from Acre (Letter Two)

12

image_header

2024-01-08T15:21:48-08:00

In March of 1217, Jacques de Vitry writes from Acre back west in order to garner more support for what would eventually become the Fifth Crusade.

In his letter, he writes of the "Prester John Christians" of the east as likely allies in the fight against Islam. Specifically Jacques refers to a figure called King David— either the son or grandson of Prester John— a figure who was himself "commonly called Prester John." This is perhaps the first moment of Prester John as a title observed within the legend's lore.

Brewer edits and translates the letter (pp. 98-100):But now in the city of Acre, I... await the arrival of pilgrims with great longing. Indeed, I believe that if we had 4,000 men of arms, through God's favour we would not be able to find anyone strong enough to resist us. Indeed, there is a great discord amongst the Saracens, and many of them, knowing their error for certain, if they dared to and had the help of Christians, they would be converted to the Lord. I also believe that the Christians living amongst the Saracens are greater in number than the Saracens [themselves]. Also, many Christian kings living in the Easter regions up to the land of Prester John, hearing of the arrival of the crusaders, would come to their help and go to war with the Saracens.

Later in the letter, Jacques explains that these "Prester John Christians" are Jacobites, or monophysites, an interesting contrast to the general trend of identify Prester John's people as Nestorians, who practice a dyophysite belief about Christ.

A few years later, Jacques expands on this faith by integrating the figure of King David, borrowed from a report called the Relatio de Davide that Jacques assimilated into the framework of the Prester John legend, as demonstrated in this so-called "Letter VII." -

1

2015-07-30T04:06:39-07:00

Peter Heylyn's Cosmographie

12

image_header

2024-01-24T18:54:56-08:00

Cosmographie in foure Bookes Contayning the Chrographie & Historie of the whole World and all the Principall Kingdomes, Provinces, Seas, and Isles, Thereof (1652)

Published in 1652, Peter Heylyn's Cosmographie presents readers with a universal geography in four books, one of which touches on the Prester John legend. His work was based on classical authors like Ptolemy and Pliny but also more contemporary English geographical work like that of George Abbot. The text went through several editions, with the sixth edition (1682) considered, according to Brooks (p. 205) as "highly regarded." The Cosmography was considered a standard work of European geogaphy into the eighteenth century.

Heylyn's text contains maps, including one of Prester John's empire by Dutch cartogropher Nicolas Visscher.

Most significantly, Cosmographie doubts Prester John's dual function as priest and king, which may not be surprising given the anti-Catholic sentiments of its author. Brewer (p. 239) also notes that Heylyn dismisses a circulating notion (proposed by Joseph Scaliger) that Ethiopians originally descended from Asia. Heylyn instead offers an account of an Asian Prester John and reasons that the Portuguese identification of John with Ethiopia resulted merely from linguistic misunderstanding.

Brooks (p. 167-8) excerpts Heylyn's description of the nature of Prester John's name and title:And yet I more incline to those, who finding that the word Prestegan signifieth an Apostle, in the Persian tongue, and Prestigani, and Apostolical man: do thereupon inferr that the title of Padescha Prestigiani, and Apostolick King, was given unto him for the Orthodoxie of his belief, which not being understood by some, instead of Preste-gian, they have made Priest-John, in Latine Presbyter Johannes; as by a like mistake, one Pregent (or Prægian as the French pronounce it) commander of some Gallies under Lewis the 12, was by the English of those times called Prior John.

-

1

2015-07-30T04:05:22-07:00

Purchas His Pilgrimes

11

image_header

2023-12-09T08:50:13-08:00

Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and others (1613)

Published in four volumes, Samuel Purchas' Purchas His Pilgrimes attempted to provide a full, Anglican overview of the world as it was known at the time. In it, he retells many of the most famous European travel narratives that highlight the diversity of Earth's inhabitants.

Although Purchas never traveled himself, he certainly familiarized himself with the theories about Prester John. He identified Prester John with the Ethiopian monarch, averring that this figure "was called Priest John, by error of Covilhā, follwed by other Portugals in the first discoverie, applying by mis-coinceit through some like occurrents in the Relations in M. Polo and others touching Presbyter John, in the North-east parts of Asia" (qtd. in Silverberg, p. 317).

As Brewer writes,

In discussing the Prester John legend, Purchas argues that his kingdom stretched from Nubia in the north to “that part where the Kingdome and Land of Manicongo lyeth,” cutting across the African continent “behind the Springs and Lakes of Nilus, going through the fierie and unknowne Countries.” He includes a detailed map of these boundaries, which encompass nearly a third of the African continent.Purchas, with scholarly acuity...reviews the various hypotheses as to the location of Prester John and the origin of his name, eventually concluding that he was once an Asian monarch whose name was mistakenly applied to the emperor of Ethiopia. (236)

Purchas' synthesis of contemporaneous travel lore recalls Mandeville. Like its predecessor, Purchas His Pilgrimes was well-received in its time and remained influential for another century, most famously inspiring the landscape and opening lines of Coleridge's "Kubla Khan." As he mentions in the well-known preface to Sybilline Leaves (1816), he fell asleep while reading Purchas, though the phrase ‘In Xanadu did Cublai Can build a stately palace" remained in his mind.

-

1

2023-11-25T12:44:02-08:00

Chronicon Anglicanum

10

plain

2023-12-03T10:58:06-08:00

According to Brewer (p. 276), this chronicle contains a "short notice in a chronicle regarding the rumours spread about Prester John at the time of the Fifth Crusade. Ralph claimed that Prester John told the Caliph of Baghdad that he would vanquish him and his realm unless the Muslims converted to Christianity.

Ralph also claimed that Prester John promised to come to the aid of the crusaders in Damietta and Jerusalem.

The Latin text can be found in Joseph S.evenson (ed.) (London, RS, 1875), p. 190. There is no known English translation. -

1

media/mini_magick20220404-4-vxi22p.jpg

2015-07-30T04:26:23-07:00

Edward Webbe

10

image_header

2023-12-11T15:53:00-08:00

Edward Webbe (1554-?) was, reputedly, an English soldier and adventurer who served in Moscow during the Russo-Crimean War. As Brewer explains in his introduction to Webbe's Travels (p. 230), Webbe was something of a latter-day Mandeville:

Edward Webbe was Chief Master Gunner of England, and during the latter half of the sixteenth century, he and his army embarked upon a journey throughout the Holy Land, Egypt, Greece, Russia and 'the land of Prester John.' Like Mandeville and other travel writers before him, Webbe extended his own travels with embellishment.

It does not seem certain that Webbe was a real person and, like Mandeville, could have been a fictional personage.

-

1

media/008695_1.jpeg

2021-07-14T07:49:32-07:00

Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile

10

image_header

2024-01-02T21:32:52-08:00

James Bruce's Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, published in six volumes, relates Bruce's travels throughout the horn of Africa to become (what he considered) the first European to discover the source of the Blue Nile River. He recorded his travels in five quarto volumes.

In discussing Ethiopia's legal system, Bruce adds another interpretation of the linguistic history of the association between Prester John and the Ethiopian negus: "These complaints [to the emperor], whether real or feigned, have always for their burden Rete O Jan hoi!, which, repeated quick, very much resembes Prete Jianni, the name that was given to this prince, of which we never knew the derivation" (qtd. in Brewer, p. 298).

-

1

2015-06-18T14:51:46-07:00

Catalan Atlas

10

image_header

2024-02-19T19:24:46-08:00

Atles català (1375)

Cresques’ “Catalan” atlas was commissioned by Prince John of Aragon so that the crown might possess a master set of nautical charts that covers both East and West. The atlas consists of twelve leaves that are mounted on folding boards.

Named after the school that Abraham resided at in Majorca, the atlas was largely influenced by the geography of Marco Polo's Il Milione; however, the map does not position Prester John anywhere near China. The atlas does contain a large illustration of Prester John, but locates him in Nubia, accompanied with the text (qtd. in Brewer, p. 322):A quest rey de Nubia esta en guerra e armes [ab los] chrestians de Nubia qui son so[ts] la senyoria del enperador de Etiopia e de la terra de Preste Johan

Though Prester John features prominently on the map, Cresques clearly positions Mansa Musa to command the most attention among the depicted African figures.

For more on the map, see Grosjean's edition.

Translation of legend on map of Cresques by G.R. Crone. -

1

media/Screen Shot 2018-01-09 at 9.11.43 PM.png

2015-06-15T15:07:44-07:00

History of the Tartars

9

image_header

2023-12-31T10:55:51-08:00

Historia Tartarum (c. 1246)

Most of Ascelin’s journey to the land of the Tartars is lost, but that which remains, recorded by Simon of Saint-Quentin, was kept alive by Vincent of Beauvais in his Speculum Historiale.

As Morgan (p. 164) relates, "Simon had evidently picked up the story of Toghril's defeat at the hands of Chinggis Khan, and his subsequent death. For him, though, Chinggis's defeated enemy remains King David, son of Prester John, king of India."

In the portion of the narrative that survives (that which was transcribed by Vincent of Beauvais), Ascelin also reports that Prester John has integrated his family into the Mongol royal family by betrothing Prester John’s granddaughter to Chinggis Khan.

For more on Simon’s text and journey, see Guzman and Brewer (pp. 155-159). -

1

2015-06-15T11:04:47-07:00

Albéric of Trois-Fontaines

9

image_header

2024-01-18T20:20:30-08:00

A Cistercian chronicler of the Trois-Fontaines abbey in eastern France, Albéric (d. c.a. 1252) records the Prester John letter as first appearing in 1165 in his chronicle.

Brewer (p. 146) introduces Albéric:"Alberic's chronicle, penned progressively from 1232 to 1241, discusses various aspects of the Prester John legend, providing accounts of the Prester John Letter, Alexander Ill 's letter, the Fifth Crusade, and giving in particular further details of the conquests of the Mongols in Russia and Eastern Europe. Alberic was the first Christian outhor who acknowledged the Mongols might be 'neither Christians nor Saracens.' At the end of this excerpt, Alberic changed his mind about associating Prester John with the Mongols, and put forward the idea that the Mongols killed Prester John and took over his domain, an idea that became increasingly popular as an explanation for why the belligerent Mongols were initially thought to be a benevolent Christian kingdom." -

1

media/Screen Shot 2023-12-13 at 10.07.06 PM.png

2023-11-22T14:52:21-08:00

De Emendatione Temporum

7

image_header

2024-01-05T17:29:11-08:00

Written by Joseph Scaliger (1540-1609) and published in 1583, De Emendatione Temporum ("Of the Correction of Times") is described by Elizabeth Ott of the Chapel Hill Rare Book Blog as an attempt to "formalize the science of chronology," drawing on "Persian, Arab, Greek, Roman, and other ancient traditions, identifying and correcting the errors of his predecessors to synchronize various cultures’ accounts of history."

Under these ambitious auspices, Scaliger authors an influential account of the Prester John legend. Attempting to reconcile the earlier theories of an Asian Prester John with the more contemporary theories of Prester John as Ethiopian negus, Scaliger proposes that Prester John led an exiled group of Mongols in Ethiopia. This group, Scaliger proposes, were sent to Africa in defeat at the hands of Ghengis Khan.

As edited in Brewer (p. 225):In our recollection, there were in Italy certain churches of the Christian Ethiopians, who they call Abassins or Abissins... Indeed, by the navigations of the Portuguese, and by the splendid book of the journey of the Portuguese priest Francisco Alvarez, who penetrated into the inmost Ethiopia, one may learn many things about those men and their rites. Once, all Africa from the Nile's final mouth, to the Gaditan straits [i.e. the Straits of Gibraltar], and likewise from the Tyrrhenian Sea to beyond the Equinox towards the south, was full of Christian churches and cities, and this great tract of lands was obedient to the one Bishop of Alexandria. But if there are any churches remaining today in those parts, they recognise that patriarch alone, like these Ethiopians, being discussed now, and whom the lonely deserts and difficult routes defend from the general wasteland of Africa... Before the arrival of the Portuguese in Ethiopia, the name of the Ethiopian Christians alone was scarcely known to us, and their falsely named emperor Prestegiani; since that name does not belong to he who reigned in Ethiopia, but he who reigned in Asia three hundred years previously, a long way distant... they falsely call him Prestegiani, and [to say] that this Ethiopian is the same as that Asian man out of the itinerary of Paul the Venetian [i.e. Marco Polo] because they are both Christian is utter nonsense. It is indeed correct that three hundred years previously, certain Ethiopian kings ruled far and wide in Asia, especially in Drangiana, at the ends of Susa, and in India, until the emperors of the Tartars expelled them from all of Asia, and they were the first ones defeated, so they say, by Chingis, King of the Tartars, having killed their emperor Uncam... all those Ethiopians who had been thrown out of the kingdom of the Mongols and Chinese and were driven all the way to furthest Africa.

As Brewer (p. 225) mentions, Scaliger's theory was challenged by Peter Heylyn, who, in his Cosmographie (1652), writes that such a theory was "found in no record but in Scaliger's head." Others texts, such as Samuel Purchas' Purchas His Pilgrimes (1613) and Athanasius Kircher's China Illustrata (1667). -

1

media/Screen Shot 2021-07-07 at 8.39.26 PM.png

2021-07-07T14:16:35-07:00

Historia Tartarorum Ecclesiastica

6

image_header

2023-12-13T16:24:03-08:00

Published in Germany in 1741, Johann Lorenz von Mosheim's Historia Tartarorum Ecclesiastica is very much similar to Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia before him and Patrick Nisbet in his An Abridgment of Ecclesiastical History (1776) after.

Von Mosheim describes the emergence of Prester John in the Mongol era, following the death of "Coiremchan, otherwise called Kencham":it was invaded, with such uncommon valour and success, by a Nestorian priest, whose name was John, that it fell before his victorious arms, and acknowledged this warlike and enterprising presbyter, as its monarch. This was the famous Prester John, whose territory was, for a long time, considered by the Europeans as a second paradise, as the seat of opulence and complete felicity. As he was a presbyter before his elevation to the royal dignity, many continued to call him presbyter John, even when he was seated on the throne but his kingly name was Ungchan (qtd. in Brewer, p. 261)

He then retells the oft-repeated story of King David, Prester John's son, and the former's defeat at the hands of Genghis Khan.

-

1

media/Screen Shot 2023-12-04 at 10.05.02 PM.png

media/Screen Shot 2023-12-04 at 10.05.02 PM.png

2023-12-04T12:50:52-08:00

Russia

6

image_header

2023-12-08T18:33:26-08:00

German scientist and geographer Johann Gottlieb Georgi (1729-1802) discusses earlier failed theories as to the identity of Prester John and offers his own argument: that Prester John and the Dalai Lama are the same person. He documents these ideas in his 1780 Russia, or, a Complete Historical Account of all the Nations which Compose that Empire.

Georgi begins his passage by citing earlier accounts of Prester John that proved incorrect, including those of John of Plano Carpini, William of Rubruck, and Marco Polo. After discussing the failures of the Portuguese to correctly identify Prester John, Georgi offers his theory (qtd. in Brewer, pp. 267-279):But we must first proceed to give some accounts of Dalai Lama. He lives in a pagoda on the mountain Potala, which, according to the Jesuit Gaubil, is under 290 6' northern latitude, and 250 58' western longitude from Pekin [i.e. Beijing].

His followers explain the nature of his immortality in the following manner: that his soul, afier the death of his body, passes into another human body which is born exactly at that time, and this man is the new Dalai Lama. (Others relate that they keep a young man in the pagoda during the life of the Dalai Lama, who is to succeed him).

Almost all the nations of the East, except the Mohammedans, believe the metempsychosis as the most important article of their faith; especially the Indians, the inhabitants of Tibet, and Ava [?], the Perguans [?], Siamese, Mongouls, all the Kalmucs [Kalmyks], and the greatest part of the Chinese and Japanese. According to the doctrine of the metempsychosis, the soul is always in action, and never at rest· for no soonef does she leave her old habitation but she enters a new one. The Dal~i Lama being a divine person, he can find no bener lodging than the body of his successor; or, properly not the 50u l1 but the Fo residing in the Dalai Lama which passes into his successor...

...The name Pretre Jean, or Juan, was mistakenly heard by the first Europeans that visited tbese regions. And their fancy working upon it, formed many extravagant ideas which were received and cherished in Europe. These travellers perceived a certain resemblance between the sound of a word in the Mongolian and Tibetan languages with that of a French, Italian, and Portuguese word. Unused to the study of languages, they imagined that such words as had a similar sound must have likewise the same signification in the language of Tibet and of the Mongouls which they bore in some of the European. This idea being once received, many fantastical etymologIes and fables naturally arose, as that about a certain Indian Johannes Presbyter, etc.

Now, if we can admit that the missionaries of the Nestorians came into these countries (which almost every competent judge in such matters will allow) then the Nestorian patriarch and Prester John are one person; at least according to the rules of etymology. And this Prester John being a Christian, he must have been the Catholicus of the Nestorians; or perhaps only a bishop sent by the Catholicus, who in these distant regions assumed a greater title than was strictly due to him. In the pursuit of these enquiries we shall find this Prester Jobn, or this Nestorian Catholicus, to be likewise one and the same with the Dalai Lama...

...All these circumstances seem sufficiently to prove that the Catholicus, Preste Gehan, and Dalai, are only one person.

-

1

media/Map_of_Angelino_Dulcert_cropped.jpg

media/fifth-crusade-siege-of-damietta-1218-photo-researchers.jpg

2018-01-08T15:03:27-08:00

History of Damietta

6

image_header

2022-09-02T09:37:49-07:00

Oliver of Paderborn was in attendance of and wrote a theologically-tinged chronicle of the Fifth Crusade sometime in the late 1220s. Like Jacques of Vitry, he tells of the mysterious King David, here the son of Prester John, prophesied to help the West vanquish Islam. Brewer (pp. 135-39) edits and translates the portion of the chronicle concerned with Prester John:

Before the capture of Damietta, a book written in Arabic became known to us... It also added that Damietta would be captured by the Christians... In addition, it foretold that a certain king of the Nubian Christians would destroy the city of Mecca and cast out the scattered bones of Muhammad the false prophet...

I have found David, My servant; with My holy oil have I anointed him King of the Indians, whom I have ordered to avenge My wrongs, to rise up agains the many-headed beast. To him I have brought victory against the King of the Persians... King David, who they call the son of Prester John, won the first fruits against him [King of the Persians] then he subjugated to himself other kings and kingdoms, and as we have learned from a report that has reached far and wide, there is no power on earth strong enough to resist him. He is believed to be the executor of divine vengeance, the hammer of Asia. -

1

2023-11-22T15:37:42-08:00

Liber de Rebus Memorabilibus

5

plain

2023-11-26T22:03:01-08:00

Written by Henry of Herford

Brewer (p. 283) describes the text:A derivate account of Prester John, which borrowed from the tmdition of King David being killed in 1202 by the Tartars (the earliest surviving exemplar of which is in the Annates Pegavienses... Another source which the author calls 'Egkardus' (?) repeating the familiar story of Prester John and his family being killed and maimed by the Mongols before they emerged from Asia, as well as excerpts from Otto of Freising and the Prester John Letter: Augustus Potthast (ed.), Liber de Rebus Memorabilioribus sive Chronicon Henrici de Hervordia (Goningen, 1859), pp. 175-6. No translation known.

-

1

2015-06-15T15:08:35-07:00

Chronica Albrici Monachi Trium Fontium

5

image_header

2023-12-31T11:11:25-08:00

Chronica Albrici Monachi Trium Fontium (1232-1253)

Written over ten years in his home monastery of Trois-Fontaines, Alberic of Trois-Fontaines' Chronicle treats world events up to the current time.

The conventional dating of the Letter of Prester John to 1165 derives from Alberic, who explains that the letter was initially sent out to several European kings, but most especially to Frederick Barbarossa and Emperor Manuel.

As Brewer (p. 11) explains, Alberic's Chronicle, along with scribal addition, dated to 1170, in one thirteenth-century copy of the Letter, comprise the only extant evidence regarding the original date of composition of the letter of Prester John.

Alberic's chronicle also contains summaries of the mid-thirteenth century Dominican missions to the Mongols, and he was the first author to point out that the Mongols might be "neither Christians nor Saracens" (qtd. in Brewer, p. 146).

Alberic narrates the death of Prester John as follows (qtd. in Brewer, p. 149):Indeed, at that time there arose the Tartars, a certain barbarian people under Ihe power of Prester John. When Prester John was in battle against the Medes and Persians, he called them to his aid, and placed them in forts and fortifications; they, seeing they were stronger [than him], killed him and occupied his land for the most part, setting a king above them, as though he was Prester John; and from that time on they did many evils in the land, such that this year they killed 42 bishops in Greater Armenia.

- 1 media/Screen Shot 2023-12-13 at 6.58.48 PM.png media/Screen Shot 2023-12-13 at 11.33.05 PM.png 2023-12-13T21:52:18-08:00 Atlas Chinesis 5 image_header 2023-12-13T22:40:55-08:00 Dutch minister and headmaster Arnold Montanus wrote Atlas Chinesis (1671) as a compendium of previously reported information about China. As Brewer notes (p. 248), he relied principally on members of the Dutch East India company, and his account of the geography of Prester John's kingdom resembles that of Johannes Nieuhof's Embassy from the East-India Company, published two years later. Montanus places Prester John's kingdom west of Sichuan, putting him in Tibet (here called Sifan).

-

1

2021-09-08T09:30:46-07:00

The Elyseus Narrative

5

plain

2024-01-08T18:00:39-08:00

Composed anonymously in the late twelfth century, this short text describes the legend of an Indian-born priest who travels to the court of Prester John. Some of the material appears to be borrowed from the de Adventu (or at least suggests its influence).

Both texts share a preoccupation with the Apostle Thomas, though the Elyseus narrative places the miracles associated with this figure in a curious (and highly relevant) locale: Edessa.

The Elyseus narrative situates the miracles of St. Thomas on a mountain just outside of this recently lost Crusader county. Edessa was regarded as an important locale, both for its Christian population and for its strategic location as a Christian gateway to the East. Edessa had also been historically considered a hotbed of Nestorianism, Prester John’s reputed faith, ever since the School of Edessa’s support of Nestorius in the fifth century. While Jerusalem might be the center of the Christian world, Edessa, the first crusader state to be established and also the first to be lost, figures as the first success in the expansion of the boundaries of a Latin Christian empire. Whatever inspired the timely conjunction that brought Edessa and Prester John’s India together suggests that reports of the events within these locales might have been circulating more closely than their geographies might otherwise indicate.

The account of Elyseus is notable also for its depiction of the Earthly Paradise, which is said here to exist on top of four mountains in India, suggesting a possible source for those who sought Prester John in Tibet.

As Brewer (p. 274) notes, the text is known in only one manuscript, edited by Zarncke (p. 122-27). There is no known English translation. -

1

2023-11-25T12:38:22-08:00

Continuatio Admontensis

5

plain

2023-12-03T11:03:36-08:00

According to Brewer (p. 275), the late 12th century Continuatio Admontensis includes "a short notice of Prester John seemingly sources from Otto of Freising," noting that, in 1141, "Prester John, King of India and Armenia, fought with the two brother kings of the Persians and the Medes, and defeated them" in the year 1141, the same as the Battle of Qatwan.

-

1

media/Screen Shot 2018-01-09 at 9.11.43 PM.png

media/Screenshot 2023-11-24 at 4.14.30 PM.png

2023-11-24T15:07:41-08:00

Riccoldo da Monte di Croce's Itinerarius

5

image_header

2023-11-24T15:53:13-08:00

Composed by Riccoldo da Monte di Croce

From Brewer (p. 281):This text repeats the familiar story of the Mongols killing Prester John... 'Then the Tartars made three squadrons. One squadron, with the Great Khan, occupied Cathay, a most wide province, all the way to the farthest India, and there they killed Prester John and occupied his kingdom, and the son of the Great Khan took the daughter of Prester John as wife'

-

1

media/Screen Shot 2021-06-10 at 1.33.54 PM.png

2015-12-12T10:29:01-08:00

English Prester John Texts

5

image_header

2021-06-11T09:47:02-07:00

Although the legend of Prester John made it to the British Isles as early as the 13th century, there are remarkably few copies of the Letter composed in English.

For the first twenty-five years of its circulation, the Letter of Prester John, so far as we know, was copied exclusively in Latin. At least 5 of the 25 extant twelfth-century Latin manuscripts were copied in England. The specific version of the Letter found in each of these English manuscripts (Redaction B) represents just one of the seventeen distinct Latin versions of the Letter. However, it is this Redaction B, found in England, which forms the basis for the majority of the vernacular copies, including French, Anglo-Norman, Occitan, Italian, Spanish, German, Welsh, Danish, Swedish, Old Church Slavonic, Russian, and Serbian Letters of Prester John. In other words, England appears to be one of the first important footholds for the legend.

Notably, the British Prester John Letters stand out for their linguistic diversity. Yet, despite the importance of the British tradition of the Letter, it is difficult to not notice a rather conspicuous absence: the lack of a Middle English version. This absence accounts, in part, for the relative marginality of this text in English-language medieval scholarship (compared to French and German traditions, for example). While the Letter found its way to the other major European medieval vernaculars by the fourteenth century, it is not until 1520 that an English-language printed version that the Letter appears, and even that was printed in Antwerp.

Despite what some might consider a crucial lack, Prester John’s British popularity continues to increase during the Early Modern and Enlightenment periods. The European production of the Letter peaked in the fifteenth century, but as it trailed off elsewhere, it continued to soar in England. Of the 48 seventeenth-century texts Brewer lists in his annotated appendix on Prester John primary sources, a whopping 22 of them —nearly half— were composed in England.

See below for other texts written in English that discuss Prester John or the legend. -

1

media/PJ OG.jpg

2023-11-22T15:24:06-08:00

Der Niederrheinischer Orientbericht

5

plain

2023-11-26T22:00:16-08:00

Brewer (p. 283) briefly discusses this text in his end-of-book chronological table of Prester John texts:

A legendary tract which intertwines various stories about India, Prester John, the three Magi, and St. Thomas the Apostle: Röhricht and Meisner (ed.), In Zeitschrift deutsche Philologie, vol. 19 (1887), pp. 1-86. No translation known.

-

1

media/Screen Shot 2023-12-13 at 6.58.48 PM.png

2023-12-13T16:08:40-08:00

Embassy from the East-India Company

5

plain

2024-01-12T19:01:40-08:00

An embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China deliver'd by their excellencies, Peter de Goyer and Jacob de Keyzer, at his imperial city of Peking : wherein the cities, towns, villages, ports, rivers, &c. in their passages from Canton to Peking are ingeniously describ'd

Dutch traveler and member of the East India Company Johannes Nieuhof (1618-1672) wrote an account of his travels to China in his Embassy from the East-India Company (1673). He places the roots of the Prester John story in that country, at what amounts to the Tibetan plateau, according to Brewer (p. 250). In other words, Nieuhof plants the seeds for the Prester John as Dalai Lama narrative path.

Nieuhof's text includes other accounts which themselves mention Prester John, including Michael Boim's Letter (1653) and Athanasius Kircher's China Illustrata (1667).