Science on the Page

Science on the Page

Jessica Fan, Charlotte Fowler, Sabrina Niu, and Dominic Pak

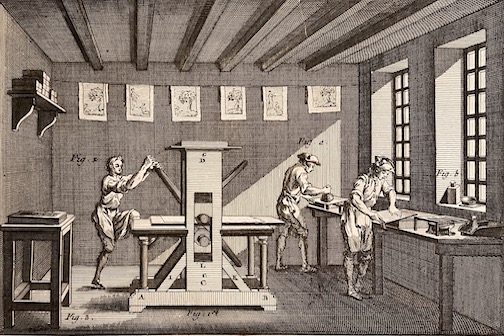

Visual aids in written materials have a long history of supplementing written text to convey more comprehensive ideas to the minds of readers. The production methods for these images, however, have gone through several iterations over the centuries. Before the digital image there was the printed image, first created using woodcuts and later using engravings. Before the printed image, there were hand-drawn and hand-illustrated images in manuscripts. Each process reflects not only the evolution of printing technology over time, but also the evolution of the role of the image in books. The ornate hand-illustrated images of the manuscript era before print reflect the role of illustrated books as valuable status symbols. Each book had to be created individually, making it less easily acquired than later mass printed books. The price of books was further increased by their intricate designs, vibrant colors, and fine gold detailing. Illustrated books of this period were limited in both audience and topic. Most people would not have had the funds to pay for these skill-intensive manuscripts. Similarly, only individuals or institutions with considerable wealth could afford to commission or purchase multiple copies of books. After the introduction of the printing press in Europe ca. 1450, books—with and without printed images—became cheaper and easier to produce. Thanks to the printing methods outlined below, books with images and figures could be mass produced, and these images became tools that scholars used to produce and communicate knowledge.The advent of the printing press (ca. 1450) allowed for books with images to be produced much faster and more cheaply than was previously possible. Before the printing press, images in manuscript books were painted by hand, requiring considerable time and cost. Early printed images were produced using two different techniques: woodcuts and copperplate engravings. With these cheaper options available, books with images became more available to the public and covered a wider range of topics. (Charlotte Fowler)

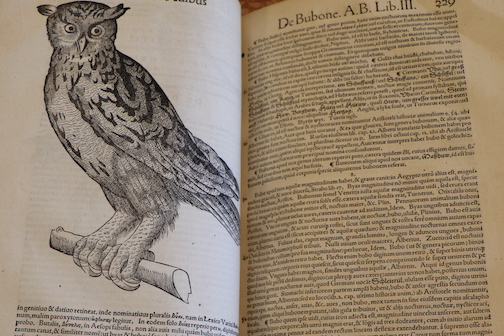

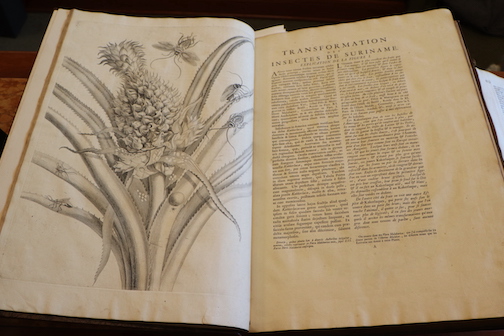

Even though these new image-printing technologies could reveal the intricate details of objects and facilitate the dissemination of knowledge, the main approach to understanding the surrounding world was not through images for scholars in the sixteenth century. At the time, European natural historians widely adopted the humanistic approach to knowledge through philology, or the study of language and its historical development. They emphasized the analysis of ancient classical (Greek and Roman) texts to make sense of the world and humanity’s place in it. During the time, some scholars in the field, such as German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs, advocated for the idea of autopsia—seeing for oneself—to attain precise knowledge about nature.[4] This emphasis on observation, nevertheless, did not mean that books were to be disregarded altogether. Fuchs himself published a profusely illustrated book on plants, De Historia Stirpium (Basel, 1542), and natural history was still a discipline largely built upon bibliographical resources rather than physical observation. For example, in his study of animals, the Swiss scholar Conrad Gessner focused on philology and privileged ancient writings about animals in his Historiae animalium (Zurich, 1551–87). Gessner claimed there was a close interconnection between human culture and nature. He dedicated the largest section of his book to associations—ways in which animals and their attributes were interpreted and related to human language, literature, and art.[5] People’s interest in animals’ symbolic meanings was also evident in emblems, a popular genre at the time that combined a symbolic image, a motto, and a poem. When scholars explored insects in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many works focused on insects with rich cultural and symbolic meanings such as bees and butterflies. Nonetheless, these works on natural history, unlike earlier works, were not solely comprised of textual descriptions but rather a combination of text and images. This change gained momentum as image-printing technology advanced and an increasing number of scholars recognized the ability of images to enhance knowledge and add authority to printed texts.

In the 1500s and 1600s, it became increasingly common for scientific books to include images. Scholars used pictures to share information, communicate their observations, and to add authority and credibility to their arguments. The visual culture of early modern science emphasized observation involved not only print technologies but also new instruments such as the telescope and the microscope. Scientific books from this period show the various approaches that scholars took, among them analysis of ancient classical texts, first-hand experience, and the interpretation of human cultures’ relationships to nature and the divine. (Sabrina Niu)

[1] Sachiko Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 29–30.

[2] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 29.

[3] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 32.

[4] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 107.

[5] William B. Ashworth, “Emblematic Natural History of the Renaissance,” in Nicholas Jardine and James Secord (eds.), Cultures of Natural History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 17–37.

[6] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 127–129.

[7] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 119.