Exploring the Human Body

Exploring the Human Body

Maya Caselnova, Ben Miller, and Kaeo Wongbusarakum

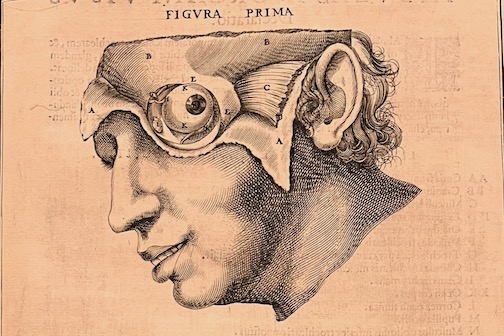

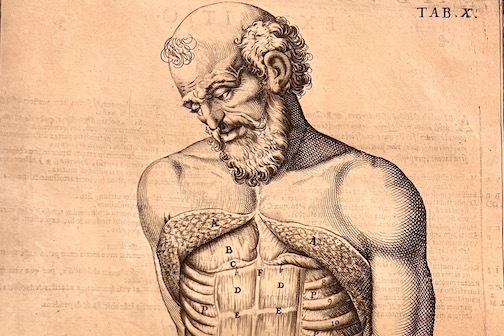

In order to understand the world around us, we must first understand ourselves. The discipline of anatomy represents the response to this innate human desire to understand and offers a glimpse into the fabric of our own biology. This broad field seeks to provide insight into the functions and organization of the human body. In the early stages of anatomical exploration, as with any scientific study, there was great discord surrounding the proper ways to conduct dissections and disseminate knowledge. Preliminary studies of human anatomy and surgery involved “the professor [reading] out the text of Galen while a barber-surgeon cut open the body.”[1] This style of dissection highlights early anatomical exploration as heavily reliant upon canonical texts and the use of intellect, rather than experience and understanding. Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) revolutionized this field when “he advocated firsthand dissections” and “ocular faith of witnesses in the dissection hall through pictures.”[2] These efforts aided the development of anatomy into a more objective and tangible area of study that led to an intimate understanding of ourselves and the fabric from which we are constructed. These books, while more scientifically focused than prior studies of anatomy, still included extravagant portraits of humanized skeletons and animated corpses — embellishments that are rarely found in the pages of modern anatomy textbooks. Vesalius’ insistence on including images in books and advocating that physicians personally complete dissections was met with great resistance, “and [the] use of pictures did not become the norm in anatomical works even in the eighteenth century.”[3] Vesalius’ work has been described by scholars as a “pictorial form of argument.”[4] Through this exhibit, you will gain an understanding and appreciation for the complex arguments made through pictures in not only Vesalius’ work but the work of a curated group of influential physicians.During the 1500s there were contentious debates among physicians about the proper methods for exploring and understanding human bodies. A new method based on dissections and experiential studies renewed the study of anatomy, providing glimpses into the normally unseen and intangible insides of the human body. For the first time, people were able to visualize and appreciate these hidden interior features. This case explores three examples showing the expansion of anatomical understanding and the methods by which these discoveries were made. (Maya Caselnova, Ben Miller, and Kaeo Wongbusarakum)

Since most people were not able to attend dissections, images played an instrumental role in allowing readers of anatomy books to interact with their contents and discoveries about the human form. This reliance on images meant that early modern authors took liberties in artistic representation and depicted canonical bodies in keeping with the idea of a perfect human form. Their pursuit of perfection was synonymous with portraying God’s creation in its ideal form. This case presents two works that present anatomical knowledge through stylized artistic images. (Maya Caselnova, Ben Miller, and Kaeo Wongbusarakum)

[1] Sachiko Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 202.

[2] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 248.

[3] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 233.

[4] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 227.

[5] Alan Branigan, “History of Medical Illustration” (Association of Medical Illustrators, Illuminating the Science of Life, 1995).

[6] Kris Newby, “Stanford art students get lesson on the evolution of anatomy illustration,” (Stanford Medicine, 2017).

[7] Fabio Zampieri et al., “Andreas Vesalius: Celebrating 500 years of dissecting nature” (Global Cardiology Science and Practice, 2015).

[8] Fabio Zampieri et al., “Andreas Vesalius: Celebrating 500 years of dissecting nature”.

[9] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 215.

[10] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 204.

[11] Dolores Mitchell, “Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp’: A Sinner among the Righteous,” Artibus et Historiae 15, no. 30 (1994): 147.

[12] Mitchell, “Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp,” 147.

[13] Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature, 221.