European Explorations of the Natural World

European Explorations of the Natural World

Michael Gribbon, Avery Longdon, and Shruti Shakthivel

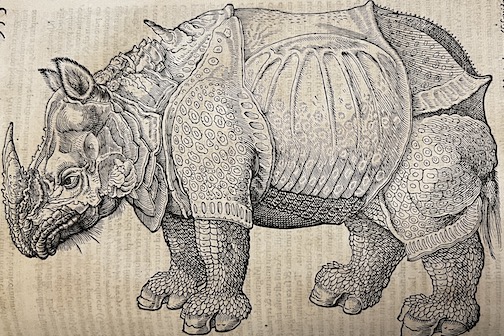

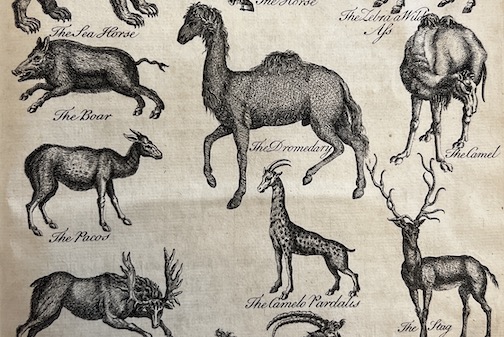

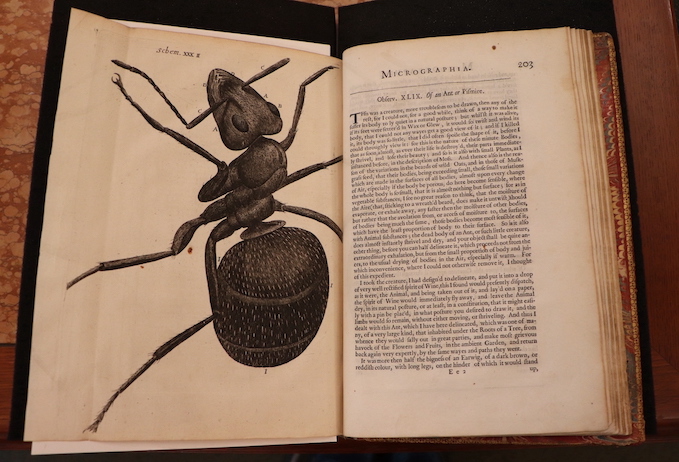

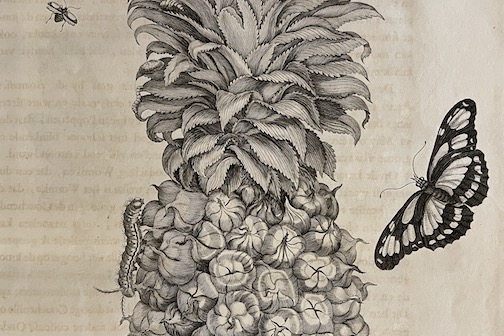

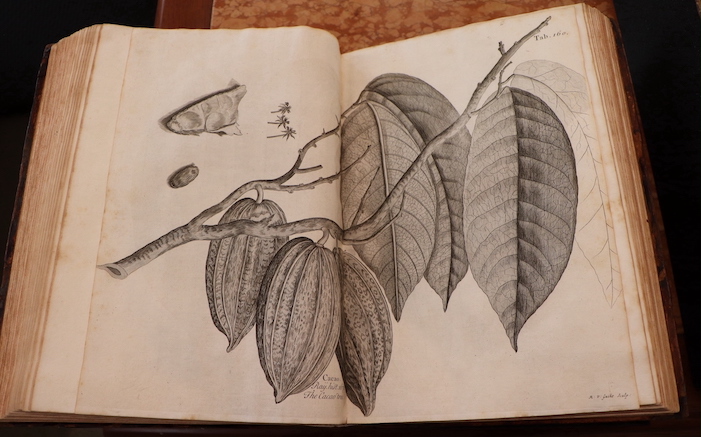

Knowledge about the natural world was especially important for scholars and learned people in the early days of printed books. Images were a way to understand what could not be seen in normal life and share specific knowledge that could not be garnered from printed text alone. The fifteenth and later centuries were periods of immense exploration outside of Europe, and as scholars left their countries to chart new lands and bring back novelties, information spread about these natural curiosities that were not native to Europe. Sketches of plants and animals new to Europe were reproduced by artists using wood blocks and later copper plate engravings, allowing them to be inserted as images in books. Often accompanied by informational text, scholars debated for decades the idea of learning about plants and animals through the use of images. Some argued that one must learn by seeing and examining the specimens firsthand. At the same time, other scholars noted the breadth of knowledge that could be gained from books in the comfort of one's own home. For example, historian Sachiko Kusukawa discusses how in the sixteenth century authors, such as Janus Cornarius, did not think images were essential to learning about plants, while authors like Leonhart Fuchs used images to visually express the details described in their texts, and further, to represent ancient knowledge about the plants they depicted.[1] As further technological and scientific advancements were made, books eventually included images of more than just novel animals and plants from faraway places but also things that were difficult to see with the naked eye. Ultimately, images related to natural history in early modern books allowed readers to visualize and experience plants, animals, or objects with which they were not familiar.Images of animals in early printed books made the unfamiliar familiar by allowing Europeans to see and learn about animals from faraway lands. The animals were illustrated based on sketches and information from other books; many if not most of the images were therefore not entirely accurate or realistic. Technological advances like the microscope also played an important part in efforts to understand and perceive previously

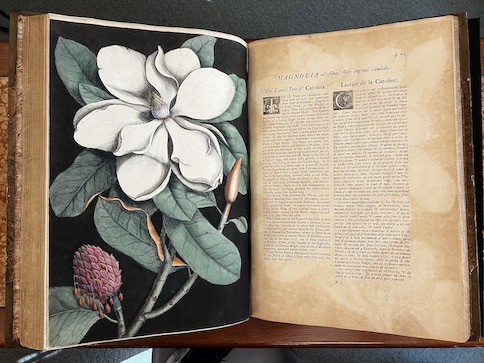

The images of plants in early modern books allowed authors to make botanical knowledge more widely accessible to readers. Naturalists sometimes voyaged to non-European regions with unfamiliar plant species, other times they studied plants in their own gardens or conducted research using botanical books. By the 1700s, authors used images to provide a detailed visual record of the plants they discovered and also to offer contextual information about the uses and cultural meanings of plants. (Michael Gribbon, Avery Longdon, and Shruti Shakthivel)

[1] Sachiko Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 111–28.

[2] William B. Ashworth, “Emblematic Natural History of the Renaissance,” in Nicholas Jardine and James Secord (eds.), Cultures of Natural History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 17–37.