Mapping Places, Mapping People

Mapping Places, Mapping People

Claire Fausett, Azriel Czerniak Linder, Hudi Potash, and Eileen Zong

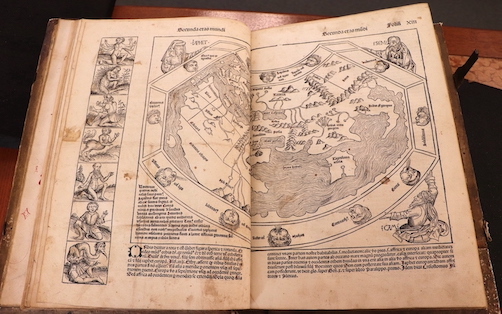

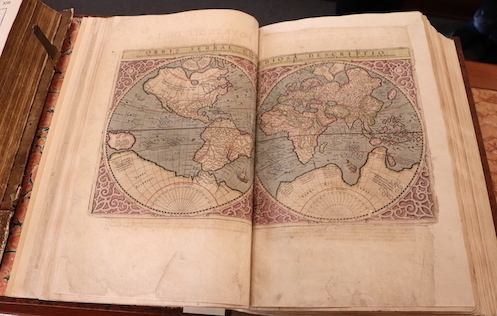

Today, we take maps for granted as factual representations of the world. Yet the very lines delegating borders and names designating places are emblematic of an ongoing process—of political, ethnic, and cultural arguments and changing identities. Maps, like any other source of media, are carefully crafted claims that advance one opinion over another. Where objective geographic measurements and subjective ideological assertions intersect is a gray area—especially when European colonial powers first began charting voyages across the world. As Surekha Davies writes in Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human, maps were “key artefacts in the fluctuating shape of the human in the European imaginary in an era of transformative, often catastrophic, cultural contacts.”[1] As European explorers encountered new peoples in their voyages, they construed these ethnographic encounters through a framework built on geographic knowledge dating from ancient antiquity. Renaissance books describing Indigenous peoples presented them through subjective, denigrating language that provided justifications for colonial projects. Similarly, our conceptions of race and ethnicity have changed drastically throughout history as a result of European colonization. Race as we understand it today is a human-made social construct for categorizing different social groups according to physical characteristics—it is not a biological fact.[2] Ancient Greek philosophers and Renaissance naturalists believed that human beings were governed by natural laws, and that human bodies varied with climate and geography. More extreme environments were thought to impair peoples’ higher mental faculties and deform their souls. This argument provided the theoretical basis for the expectations of Europeans to encounter monstrous or sub-human peoples during voyages to the Americas.[3] Indeed, the concept of “white people” did not exist until English explorers encountered people of the East Indies. Over time, the concept of whiteness evolved to encompass anyone who looked “European” and contrast against groups that Europeans deemed “savage” or “subhuman”—especially Indigenous and African peoples. By examining Renaissance images portraying voyages and encounters with Indigenous peoples, it becomes clear that we must challenge modern notions of objectivity, whether those are in relation to maps or people.Beginning in 1492, European voyages to the Americas completely upended conceptions of geography and space. Over the following centuries, European maps began to feature larger land areas and regions they had not previously depicted in order to educate and instill wonder among the public. World maps expanded to depict both larger and more finely detailed geographic spaces, and books represented specific locations or regions within the Americas from a Eurocentric viewpoint. Maps and geographic treatises were closely intertwined with the political goals and aims of European empires. (Azriel Czerniak Linder)

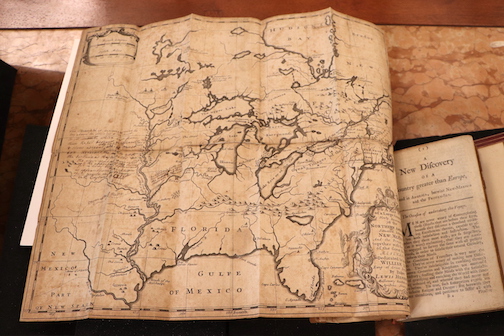

As Europeans explored the Americas, the authority of maps came from travelers’ firsthand observations. In turn, this meant that new maps were highly specific to the contexts and goals of new colonies and settlement efforts. One explorer, Louis Hennepin, traveled to North America with the intention of converting Indigenous people to Christianity. He drew a map of areas he visited with forts, settlements, ports, and other key locations and indicated the navigation routes linking these sites. Later observers noted that the Mississippi River was misrepresented in Hennepin’s map, showing that the act of mapping was a continuous and iterative project for cartographers. (Hudi Potash)

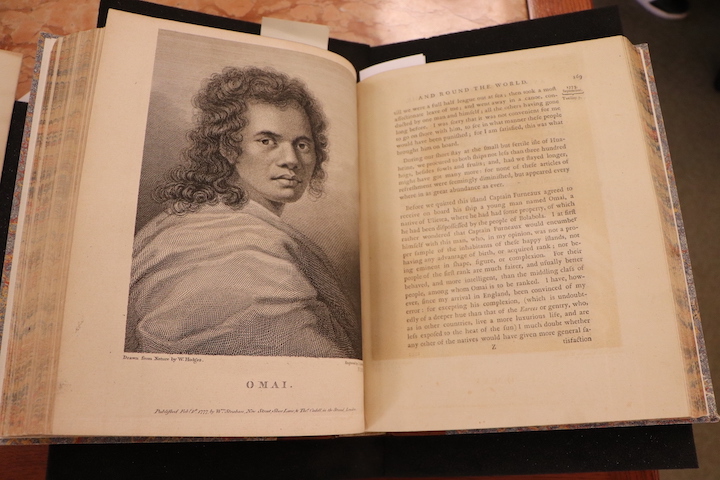

English colonial voyages to Australia, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas set in motion impactful and culturally destructive encounters that contributed to the development of the British Empire. Captain James Cook’s published account of his voyages urged Britain to reap “the full advantages of her own discoveries.” The maritime charts included in Cook’s publications would later become essential for British settlement of Australia and New Zealand. Similarly, James Adair wrote in the dedication to his book that he hoped to “promote an accurate investigation and knowledge of the American Indians . . . and the happy settlement of the fertile lands around them.” (Claire Fausett and Eileen Zong)

[1] Surekha Davies, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps, and Monsters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 2.

[2] "Historical Foundations of Race." National Museum of African American History and Culture. Accessed October 30, 2022. https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/historical-foundations-race

[3] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 2.

[4] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 1–2.

[5] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 47.

[6] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography,60.

[7] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 88.

[8] J.B. Harley, "Maps, Knowledge, and Power," in Paul Laxter (ed.), The New Nature of Maps: Essays on the History of Cartography (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 67.

[9] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 115.

[10] "World map," woodcut, in Hartmann Schedel, Liber Cronicarum [Nuremberg Chronicle] (Nuremberg, 1492)

[11] David Turnbull, "Cartography and Science in Early Modern Europe: Mapping the Construction of Knowledge Spaces," Imago Mundi 48, no. 1 (1996): 5-24.

[12] Keith Hodgkinson, "Standing the World on its Head: A Review of Eurocentrism in Humanities Maps and Atlases," Teaching History 62, (1991): 19.

[13] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 4.

[14] “Mercator’s Atlas of Europe,” The British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/mercator-atlas-of-europe, accessed November 2, 2022 .

[15] “A Map of a Large Country Newly Discovered," copperplate engraving, in Louis Hennepin, A new discovery of a vast country in America…,(London, 1699)

[16] Graham Huggan, “Decolonizing the Map: Postcolonialism, Poststructuralism and the Cartographic Connection,” in Graham Huggan (ed. ), Interdisciplinary Measures: Literature and the Future of Postcolonial Studies (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008), 67.

[17] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 2.

[18] Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 10.

[19] James Adair, The History of the American Indians;: Particularly Those Nations Adjoining to the Mississippi, East and West Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, and Virginia:... (London, 1775).

[20] James Cook, A Voyage towards the South Pole and Round the World (London, 1777).