Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder): Doctor Blass (Zalmen Pt. 5)

Doctor Blass (Doktor Bles)

from Zalmen the Cobbler: Chapters about his 70 years of Life in America (Zalmen der shuster: kapitlen vegn zayne zibtsik yor lebn in Amerike) by Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder). Los Angeles: Chaver-Paver Book Committee, 1955: 215-219.

Translated by Caroline Luce, edited by Hershl Hartman.

Recalling those years in Los Angeles, memory must turn to Doctor Blass, Chaim Shapiro, Peter Kahn. Each of them were renowned and were beloved by the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles for their care for the community, defense of the poor, spreading culture among the public, building important social institutions. These three: Doctor Blass, Pete Kahn, and, may he be granted still more years, Chaim Shapiro, can be called the oves [biblical forefathers], the fathers of the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles.

Recalling those years in Los Angeles, memory must turn to Doctor Blass, Chaim Shapiro, Peter Kahn. Each of them were renowned and were beloved by the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles for their care for the community, defense of the poor, spreading culture among the public, building important social institutions. These three: Doctor Blass, Pete Kahn, and, may he be granted still more years, Chaim Shapiro, can be called the oves [biblical forefathers], the fathers of the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles.

Blass was the doctor for those with meagre earnings. A new patient usually used to be afraid of him, because he would scream and curse and rage. But old patients knew that all his shouting and cursing was only posing and “bluff,” as is said in American, and that he was by nature an entirely good and warm mentsh.

His frequent lectures about Yiddish writers created in his audiences the desire to read Yiddish books. Many legends about his strange fondness for books, especially those in Yiddish, circulated among the “old-timers.”

One story they tell is that when a patient came to him and he asked him if he had read a certain Yiddish book, the patient answered self-importantly that he never reads “Jargonish” books, so he kicked him out of his office.

A second story they tell is that when he once called on a patient at his home and didn’t encounter any bookshelf, he began to shout at the people in the house that they were crude people and he didn’t want to have anything to do with them.

He himself bought any Yiddish book that was published. In his doctor’s office the shelves of books, mostly Yiddish, were more visible than the doctors’ instruments and little vials of medicine. He was constantly seen reading. Often his patients in the front room of his office waited, because inside in his office he could not tear himself away from a book that he was reading.

Once, it is told, someone had lent him a book, the first volume of Bergelson’s writings. At around three in the morning the doorbell rang loudly, so, of course the man ran downstairs in great fear — it was Dr. Blass. What was the matter? He had finished reading the first volume and now wanted the second volume!

And when a Yiddish writer, or a scholar, would come as a guest to Los Angeles, he would see to meeting with them right away, and often enticed them to his office, allegedly to examine them, and as the other sat half-naked on the exam table, would talk for hours and hours about Yiddish literature. When he died a couple of years ago, he left behind a rich Yiddish library with many rare books that were no longer in print.

And when a Yiddish writer, or a scholar, would come as a guest to Los Angeles, he would see to meeting with them right away, and often enticed them to his office, allegedly to examine them, and as the other sat half-naked on the exam table, would talk for hours and hours about Yiddish literature. When he died a couple of years ago, he left behind a rich Yiddish library with many rare books that were no longer in print.

When my eldest daughter was approaching childbirth, on whom would I call? Doctor Blass. It was to be her first child. Her birth pangs began at evening. Doctor Blass arrived with his satchel bag of instruments, examined her, and said to her gruffly:

“There, there, why are you making such a fuss? Do you really think that you are the only woman in the world that has had pain when she gave birth?”

So he declined and wouldn’t attend to her anymore, because according to him she was panicking prematurely, that the child would come a lot later. But he nevertheless stayed in the house to wait, in case something might happen. And meanwhile, as he did in each of his Jewish patients’ houses, he looked for the bookcase. He didn’t have to look long for it in my house, finding there many Yiddish books. In the bookcase, Dr. Blass discovered a very thick book of almost all of Y. L. Peretz’s essays, published in Tsukunft (Future). Naturally, he began to read them. Read them standing. Because of his nearsightedness his nose almost touched the page. I wanted to bring him a chair so he could sit down; he cursed me straight out because I was annoying him and interrupting his reading.

So I said nothing, since such an eccentric was a dangerous, irascible person! My daughter in the meantime was groaning in pain, but he was unconcerned. He stood and read Peretz and licked his lips, like a person with a sweet tooth who delighted in some candy. My daughter, like every first-time mother, would not keep silent; it seemed to her that at that moment she was dying, at that moment leaving the world, and every minute she let out a new mind-splitting scream.

So I said nothing, since such an eccentric was a dangerous, irascible person! My daughter in the meantime was groaning in pain, but he was unconcerned. He stood and read Peretz and licked his lips, like a person with a sweet tooth who delighted in some candy. My daughter, like every first-time mother, would not keep silent; it seemed to her that at that moment she was dying, at that moment leaving the world, and every minute she let out a new mind-splitting scream.

from Zalmen the Cobbler: Chapters about his 70 years of Life in America (Zalmen der shuster: kapitlen vegn zayne zibtsik yor lebn in Amerike) by Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder). Los Angeles: Chaver-Paver Book Committee, 1955: 215-219.

Translated by Caroline Luce, edited by Hershl Hartman.

Recalling those years in Los Angeles, memory must turn to Doctor Blass, Chaim Shapiro, Peter Kahn. Each of them were renowned and were beloved by the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles for their care for the community, defense of the poor, spreading culture among the public, building important social institutions. These three: Doctor Blass, Pete Kahn, and, may he be granted still more years, Chaim Shapiro, can be called the oves [biblical forefathers], the fathers of the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles.

Recalling those years in Los Angeles, memory must turn to Doctor Blass, Chaim Shapiro, Peter Kahn. Each of them were renowned and were beloved by the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles for their care for the community, defense of the poor, spreading culture among the public, building important social institutions. These three: Doctor Blass, Pete Kahn, and, may he be granted still more years, Chaim Shapiro, can be called the oves [biblical forefathers], the fathers of the Yiddish yishuv in Los Angeles.Blass was the doctor for those with meagre earnings. A new patient usually used to be afraid of him, because he would scream and curse and rage. But old patients knew that all his shouting and cursing was only posing and “bluff,” as is said in American, and that he was by nature an entirely good and warm mentsh.

His frequent lectures about Yiddish writers created in his audiences the desire to read Yiddish books. Many legends about his strange fondness for books, especially those in Yiddish, circulated among the “old-timers.”

One story they tell is that when a patient came to him and he asked him if he had read a certain Yiddish book, the patient answered self-importantly that he never reads “Jargonish” books, so he kicked him out of his office.

A second story they tell is that when he once called on a patient at his home and didn’t encounter any bookshelf, he began to shout at the people in the house that they were crude people and he didn’t want to have anything to do with them.

He himself bought any Yiddish book that was published. In his doctor’s office the shelves of books, mostly Yiddish, were more visible than the doctors’ instruments and little vials of medicine. He was constantly seen reading. Often his patients in the front room of his office waited, because inside in his office he could not tear himself away from a book that he was reading.

Once, it is told, someone had lent him a book, the first volume of Bergelson’s writings. At around three in the morning the doorbell rang loudly, so, of course the man ran downstairs in great fear — it was Dr. Blass. What was the matter? He had finished reading the first volume and now wanted the second volume!

And when a Yiddish writer, or a scholar, would come as a guest to Los Angeles, he would see to meeting with them right away, and often enticed them to his office, allegedly to examine them, and as the other sat half-naked on the exam table, would talk for hours and hours about Yiddish literature. When he died a couple of years ago, he left behind a rich Yiddish library with many rare books that were no longer in print.

And when a Yiddish writer, or a scholar, would come as a guest to Los Angeles, he would see to meeting with them right away, and often enticed them to his office, allegedly to examine them, and as the other sat half-naked on the exam table, would talk for hours and hours about Yiddish literature. When he died a couple of years ago, he left behind a rich Yiddish library with many rare books that were no longer in print.When my eldest daughter was approaching childbirth, on whom would I call? Doctor Blass. It was to be her first child. Her birth pangs began at evening. Doctor Blass arrived with his satchel bag of instruments, examined her, and said to her gruffly:

“There, there, why are you making such a fuss? Do you really think that you are the only woman in the world that has had pain when she gave birth?”

So he declined and wouldn’t attend to her anymore, because according to him she was panicking prematurely, that the child would come a lot later. But he nevertheless stayed in the house to wait, in case something might happen. And meanwhile, as he did in each of his Jewish patients’ houses, he looked for the bookcase. He didn’t have to look long for it in my house, finding there many Yiddish books. In the bookcase, Dr. Blass discovered a very thick book of almost all of Y. L. Peretz’s essays, published in Tsukunft (Future). Naturally, he began to read them. Read them standing. Because of his nearsightedness his nose almost touched the page. I wanted to bring him a chair so he could sit down; he cursed me straight out because I was annoying him and interrupting his reading.

So I said nothing, since such an eccentric was a dangerous, irascible person! My daughter in the meantime was groaning in pain, but he was unconcerned. He stood and read Peretz and licked his lips, like a person with a sweet tooth who delighted in some candy. My daughter, like every first-time mother, would not keep silent; it seemed to her that at that moment she was dying, at that moment leaving the world, and every minute she let out a new mind-splitting scream.

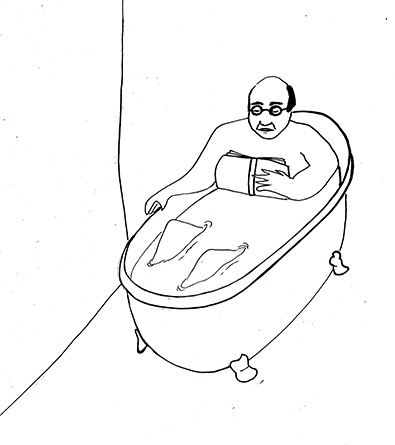

So I said nothing, since such an eccentric was a dangerous, irascible person! My daughter in the meantime was groaning in pain, but he was unconcerned. He stood and read Peretz and licked his lips, like a person with a sweet tooth who delighted in some candy. My daughter, like every first-time mother, would not keep silent; it seemed to her that at that moment she was dying, at that moment leaving the world, and every minute she let out a new mind-splitting scream. I looked and saw him taking Peretz with him into the bathroom and closing the door behind him. A little time passed — he didn’t come back out. And my daughter was screaming so loudly that my Goldie and I couldn’t endure it any more. My Goldie motioned to me to knock on the door of the bathroom. I said to her that we should be patient for a little while longer. We waited and waited — still he didn’t come out. Then I heard some water flowing there in the bathroom, as though someone were filling the bathtub. I didn’t understand: if Dr. Blass were to be taking a bath in my house, such a thing would have been entirely bizarre; a doctor coming to see a patient, and suddenly taking a bath.

Meanwhile my daughter became somewhat quieter, fell asleep, and we of course rejoiced, except that the fact that Doctor Blass was still in the bathroom would not let us rest. I stood at the door and listened — the water wasn’t running anymore, and it was as still as though no one was in there. Then I became frightened. Who knows what, God forbid, what could have befallen him in there? I finally slowly opened the door, and looked around: the honorable fellow was sitting Adam-naked in a bathtub of hot water, and in his hands the thick volume of Y. L. Peretz and his near-sighted eyes running across the lines, and his lips moving, as though licking his lips over some exquisite delicacy. So I let him sit in the tub and enjoy Peretz as long as my daughter slept. Later, however, when she began really screaming, he sprang right out with such youngster’s nimbleness, and in a minute or two had wiped off, dressed, and began to work on the new mom with very dexterous hands.

So I let him sit in the tub and enjoy Peretz as long as my daughter slept. Later, however, when she began really screaming, he sprang right out with such youngster’s nimbleness, and in a minute or two had wiped off, dressed, and began to work on the new mom with very dexterous hands.

After this story, it was a long time before I saw Dr. Blass again. But I heard about his lectures, and about his efforts on behalf of Yiddish books, drama societies and other cultural institutions.

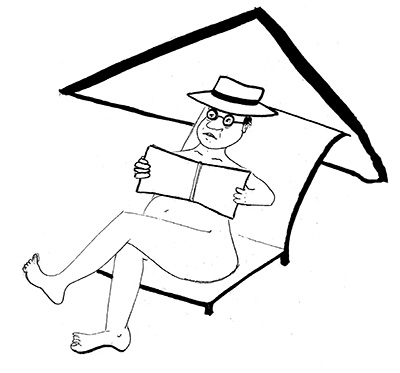

Once, after many, many years, I came as a guest to the Arbeter Ring summer camp. This was during the day. Whom did I meet first? Doctor Blass. And where? Sitting on the roof of a bungalow. And in what way? Adam-naked. And what was he doing there? Sun bathing and reading a book...

Meanwhile my daughter became somewhat quieter, fell asleep, and we of course rejoiced, except that the fact that Doctor Blass was still in the bathroom would not let us rest. I stood at the door and listened — the water wasn’t running anymore, and it was as still as though no one was in there. Then I became frightened. Who knows what, God forbid, what could have befallen him in there? I finally slowly opened the door, and looked around: the honorable fellow was sitting Adam-naked in a bathtub of hot water, and in his hands the thick volume of Y. L. Peretz and his near-sighted eyes running across the lines, and his lips moving, as though licking his lips over some exquisite delicacy.

So I let him sit in the tub and enjoy Peretz as long as my daughter slept. Later, however, when she began really screaming, he sprang right out with such youngster’s nimbleness, and in a minute or two had wiped off, dressed, and began to work on the new mom with very dexterous hands.

So I let him sit in the tub and enjoy Peretz as long as my daughter slept. Later, however, when she began really screaming, he sprang right out with such youngster’s nimbleness, and in a minute or two had wiped off, dressed, and began to work on the new mom with very dexterous hands.After this story, it was a long time before I saw Dr. Blass again. But I heard about his lectures, and about his efforts on behalf of Yiddish books, drama societies and other cultural institutions.

Once, after many, many years, I came as a guest to the Arbeter Ring summer camp. This was during the day. Whom did I meet first? Doctor Blass. And where? Sitting on the roof of a bungalow. And in what way? Adam-naked. And what was he doing there? Sun bathing and reading a book...

| Previous page on path | Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder), page 5 of 13 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder): Doctor Blass (Zalmen Pt. 5)"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...