Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder): California, Here We Come! (Zalmen, Pt. 1)

California, Here We Come! (Forn mir, heyst es, keyn kalifornie)

from Zalmen the Cobbler: Chapters about his 70 years of Life in America (Zalmen der shuster: kapitlen vegn zayne zibtsik yor lebn in Amerike) by Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder). Los Angeles: Chaver-Paver Book Committee, 1955: 199-202.*

Translated by Caroline Luce, edited by Hershl Hartman.

I got Goldie to agree that if I established myself in California and if I were not snatched up by a rich widow there, I would send for her and for the children. Goldie laughed and cried and baked and cooked and filled perhaps a whole sack of food for my journey. She did not forget to include two little bottles of her good home-made wine. And when I took a sip of that wine I felt a tug at my heart for her as though she had purposefully mixed a magic potion in it to make me long for her even more.

The truth is that I had carried about with me the dream of California for four years, since comrade B. [Baruch Charney] Vladeck had come to Nashville four years earlier. He was a splendid speaker, with a moving voice, and in Twin Hall on Church Street where he spoke then, among those who came to hear him were not only our folks, but even religious Jews and Zionists. His words were like poetry and he painted a picture for us of two Americas — the America of the rich and the America of the poor. He pointed to Los Angeles as an illustration. There was no place, he said, where these two Americas were more blatantly visible than in Los Angeles.

The rich, the one-time owners of small garment shops, had saved enough money in the East and had come to the mild climate to live in luxury, while their victims, who worked in their shops, having long accumulated lung-disease, heart-disease, asthma, and rheumatism, had come to the mild climate to cure themselves. The rich buy themselves palaces at the seashore and in the hills while their victims struggle to survive day by day.

But despite that, however, he said, the wonderful California sky shines for all, poor and rich. And he began to describe California’s blessed nature, the tall palm trees, the golden-hued oranges, the sunny days, fragrant nights, so that I and probably everyone in the hall was taken with the desire to spend at least one day in America’s Garden of Eden, as Vladeck called California.

So here I am, it seems, on the way to America’s Garden of Eden, but I am somehow not too joyful at heart. It was the end of March and should have been somewhat mild, almost Spring-like, but in Chicago a snow-storm was raging and when we left Chicago the snow turned to cold angry rain that beat on the windows of the train all the way to Kansas City. That rain was fitting accompaniment to my sad thoughts. The unknown waiting for me in that distant land frightened me. On top of that, a strange woman scolded me without reason or justification. She was skinny and

She was skinny and

small, with black, angry eyes like those of an angry puppy.

“Are you a Jew?” she asked as she approached me.

“I certainly am a Jew,” I answered, smiling broadly.

“And where might you be traveling to?” she asked, somewhat acidly. “Where might a Jew be traveling to, perhaps?” I replied good-naturedly. “It’s California that a Jew is traveling to.”

“So! To California?” she cried as if she had caught me in some evil act. “And where is your wife?” She pierced me with her sinister eyes. “Next thing you’ll say you’re single” — she would not give me a chance to utter a word — “that you have no wife and you are still a bachelor.”

“Wait now, perhaps you have a good match for me,” I said to her, making a joke. “A good match for you?” she replied, bitterly. “I have a good plague for you.”

I learned later that she was, sadly, very embittered toward all men. Her husband deserted her in New York six years ago and she had had no word from him in all that time. A landsman told her he had seen her husband in Los Angeles where he was living with another woman. She was now on her way to Los Angeles in search of her husband. She had his photograph and a clipping from “Bintl Brif” [Letter Bundle, an advice column] from the Forverts. I read the clipping and looked at the picture and took pity on him. He looked frightened and timid. As I learned from her, he had worked in a shop sewing petticoats and had earned little. I gathered she had nagged him quite a bit.

She also showed me a picture of herself when she was still unmarried. It made me realize how greatly the hardships of life can transform a human being. The picture showed a charming, lively young woman with genuine feminine attraction, and now she was shrunken, haggard and embittered.

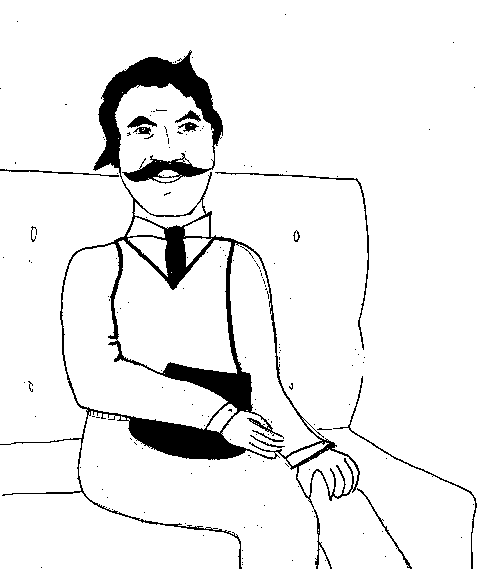

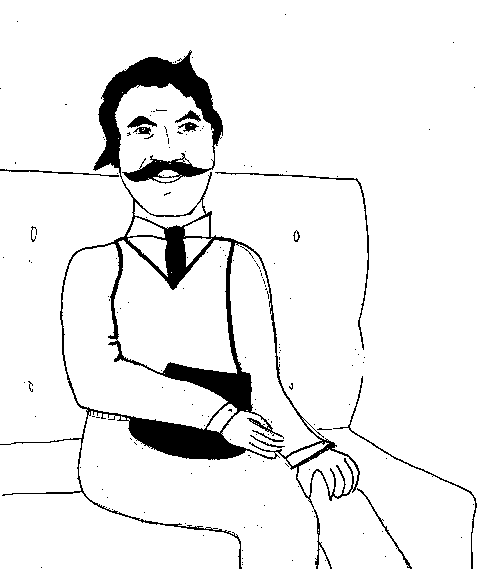

She somehow could not rest. She went from coach to coach, seeking out young Jewish men on their way to California without their wives and cursed each of them. Later I met a Mr. Nadison who was also bound for California and he told me, laughing, that he had also received a fine howdy-do from the aforementioned woman. This Mr. Nadison was a Jew from Elisavetgrad (Ukraine). He was short, but with broad shoulders, with a thick mane of black hair and an even thicker mustache. Looking at his round face, red cheeks, and laughing brown eyes, you would have supposed he lacked for nothing. But he lacked a great deal. All he needed was a pair of healthy lungs. He had been a cigar-maker in New York and had acquired a pair of truly ‘fine’ lungs. Nevertheless, quips and jokes never left his lips nor laughter his eyes. He had a very fine tenor voice and kept singing all the time. He was traveling with great faith to the golden land. He would become a farmer, he told me.

This Mr. Nadison was a Jew from Elisavetgrad (Ukraine). He was short, but with broad shoulders, with a thick mane of black hair and an even thicker mustache. Looking at his round face, red cheeks, and laughing brown eyes, you would have supposed he lacked for nothing. But he lacked a great deal. All he needed was a pair of healthy lungs. He had been a cigar-maker in New York and had acquired a pair of truly ‘fine’ lungs. Nevertheless, quips and jokes never left his lips nor laughter his eyes. He had a very fine tenor voice and kept singing all the time. He was traveling with great faith to the golden land. He would become a farmer, he told me.

Thus, we journeyed together until we arrived at the large station in Ogden, Utah, where a mountain cast a spell over me. From the railroad station the mountain was clearly visible. White at the peak and pink and blue at the foot, it appeared be at hand’s reach. I was strongly drawn to it. Nadison did not want to leave the train with me. It was early morning, the sun was shining, with the air cool and bracing like strong drink. From the station the mountain looked so near, but the more I walked the more distant it kept getting from me. I went on and on and on and on. And then it dawned on me that I had only an hour’s time and the train might play a trick on me and leave without me. So I turned back. But before I made any progress back, I saw in the distance that the train was already in motion and soon it took on more spirit and was going off quickly, quickly.

But somehow it didn’t matter to me. On the contrary, a sense of joy descended upon me. The reason was that my nose, like those of all cobblers exposed constantly to the strong odors of leather and chemical stains, had been stopped up for years and now, suddenly, it was clear, entirely open, and breathed freely the lovely fresh air of Utah.

It was the first time in many years that I felt I had a nose...Ah, ah, ah, after so many years suffocating in my cobbler’s shop, here was such beauty...it was as if I had just begun to realize what America is...

* This translation, including the title, has been adapted from Henry Goodman's translation that appeared in Clinton Street and Other Stories (New York: YKUF Publishers, 1974): 125-128, in order to make the translation more complete and accurate.

from Zalmen the Cobbler: Chapters about his 70 years of Life in America (Zalmen der shuster: kapitlen vegn zayne zibtsik yor lebn in Amerike) by Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder). Los Angeles: Chaver-Paver Book Committee, 1955: 199-202.*

Translated by Caroline Luce, edited by Hershl Hartman.

I got Goldie to agree that if I established myself in California and if I were not snatched up by a rich widow there, I would send for her and for the children. Goldie laughed and cried and baked and cooked and filled perhaps a whole sack of food for my journey. She did not forget to include two little bottles of her good home-made wine. And when I took a sip of that wine I felt a tug at my heart for her as though she had purposefully mixed a magic potion in it to make me long for her even more.

The truth is that I had carried about with me the dream of California for four years, since comrade B. [Baruch Charney] Vladeck had come to Nashville four years earlier. He was a splendid speaker, with a moving voice, and in Twin Hall on Church Street where he spoke then, among those who came to hear him were not only our folks, but even religious Jews and Zionists. His words were like poetry and he painted a picture for us of two Americas — the America of the rich and the America of the poor. He pointed to Los Angeles as an illustration. There was no place, he said, where these two Americas were more blatantly visible than in Los Angeles.

The rich, the one-time owners of small garment shops, had saved enough money in the East and had come to the mild climate to live in luxury, while their victims, who worked in their shops, having long accumulated lung-disease, heart-disease, asthma, and rheumatism, had come to the mild climate to cure themselves. The rich buy themselves palaces at the seashore and in the hills while their victims struggle to survive day by day.

But despite that, however, he said, the wonderful California sky shines for all, poor and rich. And he began to describe California’s blessed nature, the tall palm trees, the golden-hued oranges, the sunny days, fragrant nights, so that I and probably everyone in the hall was taken with the desire to spend at least one day in America’s Garden of Eden, as Vladeck called California.

So here I am, it seems, on the way to America’s Garden of Eden, but I am somehow not too joyful at heart. It was the end of March and should have been somewhat mild, almost Spring-like, but in Chicago a snow-storm was raging and when we left Chicago the snow turned to cold angry rain that beat on the windows of the train all the way to Kansas City. That rain was fitting accompaniment to my sad thoughts. The unknown waiting for me in that distant land frightened me. On top of that, a strange woman scolded me without reason or justification.

She was skinny and

She was skinny andsmall, with black, angry eyes like those of an angry puppy.

“Are you a Jew?” she asked as she approached me.

“I certainly am a Jew,” I answered, smiling broadly.

“And where might you be traveling to?” she asked, somewhat acidly. “Where might a Jew be traveling to, perhaps?” I replied good-naturedly. “It’s California that a Jew is traveling to.”

“So! To California?” she cried as if she had caught me in some evil act. “And where is your wife?” She pierced me with her sinister eyes. “Next thing you’ll say you’re single” — she would not give me a chance to utter a word — “that you have no wife and you are still a bachelor.”

“Wait now, perhaps you have a good match for me,” I said to her, making a joke. “A good match for you?” she replied, bitterly. “I have a good plague for you.”

I learned later that she was, sadly, very embittered toward all men. Her husband deserted her in New York six years ago and she had had no word from him in all that time. A landsman told her he had seen her husband in Los Angeles where he was living with another woman. She was now on her way to Los Angeles in search of her husband. She had his photograph and a clipping from “Bintl Brif” [Letter Bundle, an advice column] from the Forverts. I read the clipping and looked at the picture and took pity on him. He looked frightened and timid. As I learned from her, he had worked in a shop sewing petticoats and had earned little. I gathered she had nagged him quite a bit.

She also showed me a picture of herself when she was still unmarried. It made me realize how greatly the hardships of life can transform a human being. The picture showed a charming, lively young woman with genuine feminine attraction, and now she was shrunken, haggard and embittered.

She somehow could not rest. She went from coach to coach, seeking out young Jewish men on their way to California without their wives and cursed each of them. Later I met a Mr. Nadison who was also bound for California and he told me, laughing, that he had also received a fine howdy-do from the aforementioned woman.

This Mr. Nadison was a Jew from Elisavetgrad (Ukraine). He was short, but with broad shoulders, with a thick mane of black hair and an even thicker mustache. Looking at his round face, red cheeks, and laughing brown eyes, you would have supposed he lacked for nothing. But he lacked a great deal. All he needed was a pair of healthy lungs. He had been a cigar-maker in New York and had acquired a pair of truly ‘fine’ lungs. Nevertheless, quips and jokes never left his lips nor laughter his eyes. He had a very fine tenor voice and kept singing all the time. He was traveling with great faith to the golden land. He would become a farmer, he told me.

This Mr. Nadison was a Jew from Elisavetgrad (Ukraine). He was short, but with broad shoulders, with a thick mane of black hair and an even thicker mustache. Looking at his round face, red cheeks, and laughing brown eyes, you would have supposed he lacked for nothing. But he lacked a great deal. All he needed was a pair of healthy lungs. He had been a cigar-maker in New York and had acquired a pair of truly ‘fine’ lungs. Nevertheless, quips and jokes never left his lips nor laughter his eyes. He had a very fine tenor voice and kept singing all the time. He was traveling with great faith to the golden land. He would become a farmer, he told me.Thus, we journeyed together until we arrived at the large station in Ogden, Utah, where a mountain cast a spell over me. From the railroad station the mountain was clearly visible. White at the peak and pink and blue at the foot, it appeared be at hand’s reach. I was strongly drawn to it. Nadison did not want to leave the train with me. It was early morning, the sun was shining, with the air cool and bracing like strong drink. From the station the mountain looked so near, but the more I walked the more distant it kept getting from me. I went on and on and on and on. And then it dawned on me that I had only an hour’s time and the train might play a trick on me and leave without me. So I turned back. But before I made any progress back, I saw in the distance that the train was already in motion and soon it took on more spirit and was going off quickly, quickly.

But somehow it didn’t matter to me. On the contrary, a sense of joy descended upon me. The reason was that my nose, like those of all cobblers exposed constantly to the strong odors of leather and chemical stains, had been stopped up for years and now, suddenly, it was clear, entirely open, and breathed freely the lovely fresh air of Utah.

It was the first time in many years that I felt I had a nose...Ah, ah, ah, after so many years suffocating in my cobbler’s shop, here was such beauty...it was as if I had just begun to realize what America is...

* This translation, including the title, has been adapted from Henry Goodman's translation that appeared in Clinton Street and Other Stories (New York: YKUF Publishers, 1974): 125-128, in order to make the translation more complete and accurate.

| Previous page on path | Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder), page 1 of 13 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder): California, Here We Come! (Zalmen, Pt. 1)"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...