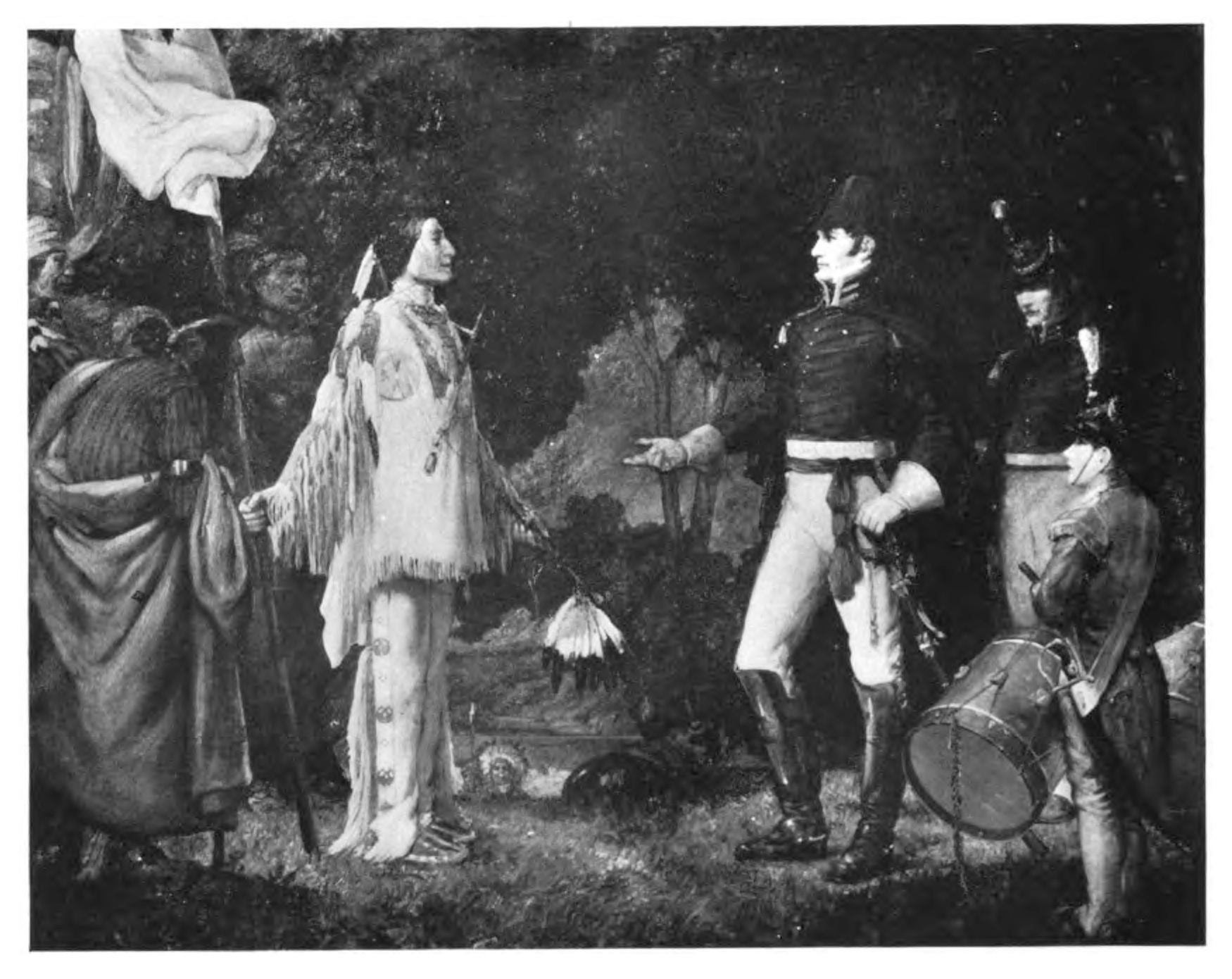

Executive Chamber - Major Whistler Conferring with Red Bird

- In Ballin's Words

- Allegory and History

- Source/Citations

Ballin described his murals in a pamphlet published in 1913:

"Major Whistler accepting a peace calumet from Red. Bird. In 1822 white men first occupied Wisconsin lead mines. About twenty persons spent the ensuing winter at Galena. The Indians had made an agreement with Colonel Johnson, permitting the whites to occupy this region. The news of the riches of the upper Mississippi lead mines soon spread, and by 1825, the spirit of migration had taken possession of the inhabitants of Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

The redman realized that his sway was ebbing, but it was too late to repulse the emigration. For three years these settlements of the lead mines were in constant apprehension, fearing the resentment of the Winnebagos. The Indians regarded it an unwarranted invasion, for which they determined to be revenged. In 1825 there was a grand council for the purpose of making a treaty for general and lasting peace between Indian and white.

In 1826 serious fear was expressed by Michael Brisbois, who believed that the Indians were ready to go on the warpath.

In 1827, the Methode family was found shockingly mangled. A Winnebago named Wa-man-does-ga-ra-ka confessed and implicated others. Red Bird was the chief of the Winnebagoes. He had confidence of all, and was known as a protector. At about this time two Indians imprisoned at Fort Crawford, and who had been confined in the guardhouse for some trivial offense, were reported killed, and this story was believed by the leading Winnebago chiefs. They resolved upon retaliation. Red Bird was called upon to 'take meat.' We-kau, said to be deformed and ugly, and Chic-hon-sic joined him. They proceeded to Prairie du Chien and went to the house of James H. Lockwood, who had left the previous day. It was their intention to kill. Red Bird then went to the home of Rijeste Gagnier. As Mrs. Gagnier was about to give the Indians something to eat Red Bird fired and killed her husband. An old soldier, Solomon Lipcap, was killed by Chic-hon-sic. Mrs. Gagnier struggled with We-kau, capturing his rifle, but was unable to use it. She ran to the village with her elder child and gave the alarm. We-kau had scalped the younger child, but she survived.

Several other demonstrations had been made by the Dakotas, the most important of which was the attack on the keel-boat Perry, on which several whites were wounded, twelve Indians killed and many injured. Red Bird and the other Winnebagos having, it was believed, fled up the Wisconsin river, General Atkinson and Colonel Dodge decided to follow. Major Whistler, in command at Fort Howard, proceeded up the Fox River. He drove them out of every hiding place, and when he reached where Portage now stands it was found that the Winnebagoes, led by Red Bird, were encamped a little more than a mile distant. A few days after they discovered the proximity of the Whistler forces Red Bird decided to give himself up.

The Indians approached, bearing three flags - two were American and the one borne by Red Bird was white. They carried no arms. Singing was heard, and those familiar with it said: 'It is Red Bird, singing his death song.' Captain Childs met them at the edge of the Fox River to ascertain their mission. An Indian, Carimaunee, answered. 'They are here. Like braves they have come in. Treat them as braves; do not but them in irons.'

In the painting Red Bird is about to hand a pipe of peace to Major Whistler. Behind are his two accomplices.

Red Bird was considered the handsomest brave of his tribe. In height about six feet, 'straight without restraint. It was impossible to conceive that such a face concealed the heart of a murderer. There he stood. Not a muscle moved nor was the expression of his face changed a particle. He appeared conscious that, according to the Indian law, he had done no wrong. His conscience was at repose. Death had no terrors for him. He was there prepared to receive the blow that should send him to the happy hunting ground to meet his fathers and brothers who had gone before him.'

Approaching Major Whistler he said: 'I am ready. I do not wish to be put in irons. Let me be free. I have given away my life.' Stooping and taking some dust in his hand he blew it away, adding: 'I would not take it back - it is gone.'"

"Major Whistler accepting a peace calumet from Red. Bird. In 1822 white men first occupied Wisconsin lead mines. About twenty persons spent the ensuing winter at Galena. The Indians had made an agreement with Colonel Johnson, permitting the whites to occupy this region. The news of the riches of the upper Mississippi lead mines soon spread, and by 1825, the spirit of migration had taken possession of the inhabitants of Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

The redman realized that his sway was ebbing, but it was too late to repulse the emigration. For three years these settlements of the lead mines were in constant apprehension, fearing the resentment of the Winnebagos. The Indians regarded it an unwarranted invasion, for which they determined to be revenged. In 1825 there was a grand council for the purpose of making a treaty for general and lasting peace between Indian and white.

In 1826 serious fear was expressed by Michael Brisbois, who believed that the Indians were ready to go on the warpath.

In 1827, the Methode family was found shockingly mangled. A Winnebago named Wa-man-does-ga-ra-ka confessed and implicated others. Red Bird was the chief of the Winnebagoes. He had confidence of all, and was known as a protector. At about this time two Indians imprisoned at Fort Crawford, and who had been confined in the guardhouse for some trivial offense, were reported killed, and this story was believed by the leading Winnebago chiefs. They resolved upon retaliation. Red Bird was called upon to 'take meat.' We-kau, said to be deformed and ugly, and Chic-hon-sic joined him. They proceeded to Prairie du Chien and went to the house of James H. Lockwood, who had left the previous day. It was their intention to kill. Red Bird then went to the home of Rijeste Gagnier. As Mrs. Gagnier was about to give the Indians something to eat Red Bird fired and killed her husband. An old soldier, Solomon Lipcap, was killed by Chic-hon-sic. Mrs. Gagnier struggled with We-kau, capturing his rifle, but was unable to use it. She ran to the village with her elder child and gave the alarm. We-kau had scalped the younger child, but she survived.

Several other demonstrations had been made by the Dakotas, the most important of which was the attack on the keel-boat Perry, on which several whites were wounded, twelve Indians killed and many injured. Red Bird and the other Winnebagos having, it was believed, fled up the Wisconsin river, General Atkinson and Colonel Dodge decided to follow. Major Whistler, in command at Fort Howard, proceeded up the Fox River. He drove them out of every hiding place, and when he reached where Portage now stands it was found that the Winnebagoes, led by Red Bird, were encamped a little more than a mile distant. A few days after they discovered the proximity of the Whistler forces Red Bird decided to give himself up.

The Indians approached, bearing three flags - two were American and the one borne by Red Bird was white. They carried no arms. Singing was heard, and those familiar with it said: 'It is Red Bird, singing his death song.' Captain Childs met them at the edge of the Fox River to ascertain their mission. An Indian, Carimaunee, answered. 'They are here. Like braves they have come in. Treat them as braves; do not but them in irons.'

In the painting Red Bird is about to hand a pipe of peace to Major Whistler. Behind are his two accomplices.

Red Bird was considered the handsomest brave of his tribe. In height about six feet, 'straight without restraint. It was impossible to conceive that such a face concealed the heart of a murderer. There he stood. Not a muscle moved nor was the expression of his face changed a particle. He appeared conscious that, according to the Indian law, he had done no wrong. His conscience was at repose. Death had no terrors for him. He was there prepared to receive the blow that should send him to the happy hunting ground to meet his fathers and brothers who had gone before him.'

Approaching Major Whistler he said: 'I am ready. I do not wish to be put in irons. Let me be free. I have given away my life.' Stooping and taking some dust in his hand he blew it away, adding: 'I would not take it back - it is gone.'"

On the walls of the Executive Chamber, Ballin chose to depict historical rather than allegorical figures from Wisconsin's history. He had done significant research on Wisconsin's history to create the historical paintings, as captured in the lengthy description he wrote for "Major Whitley Conferring with Red Bird."

On the West Wall to the right of the entrance, Ballin placed "Major Whitley Conferring with Red Bird," a meeting based on the so-called Winnebago War of 1827. The placid scene offered a triumphalist version of the encounters between Wisconsin's American settlers and its indigenous peoples that affirmed the legitimacy of American rule. Presaging his career as a novelist and filmmaker, Ballin described the encounter in heroic terms, commending both the honor of Red Bird and the righteousness of the American authorities. His account and depiction glossed over what was a very complicated and violent history.

The native peoples of Wisconsin, known as the Winnebago or Ho-Chunk, had been gradually forced off their land by Anglo settlers and in 1825, under pressure from the American military, signed a multi-tribe treaty that divided the territory that would become Wisconsin into tribal settlements. The treaty allowed the Ho-Chunk to retain control of the rich lead deposits of the region that had been their source of livelihood for generations, but Anglo America settlers ignored the treaty and continued to trespass into Ho-Chunk territory to reach the mines. Frustrated after years of having their territorial rights ignored, the Ho-Chunk launched a series of vicious attacks on settlers, with Red Bird himself responsible for murdering and scalping a family of three. Red Bird's encounter with Major Whitley was not a peaceful conference. After he turned himself over to American authorities, he was thrown in jail and died of dysentery while in custody.

Several months after Ballin completed the murals, the commissioners decided to withhold their final payment because the paintings were “not entirely satisfactory.” The daughter of one of the historical characters portrayed in the murals, General Starkweather, criticized the likeness of her father, and similar critiques of historical inaccuracies were made of other historical figures represented, including Red Bird. They asked Ballin to return and work with the room’s interior decorator, Elmer Garnsey, to make alterations. When he did, Ballin chose to redo the entire painting of the Red Bird episode (above is the updated version) and remounted it on the wall. He also redid his portrait of Colonel Joseph Bailey, a Civil War hero, and his two paintings of the former state capitols buildings in Madison. Although Ballin refused the commissioners’ requests to alter other panels in a series of feisty exchanges, they were pleased with the revisions to the Red Bird panel. As was reviewer Ada Rainey, who commented that the “historical accuracy [of the murals] is excellent, and there is an impression of reality that the scenes depicted actually took place in the early life of Wisconsin.” The mural, and others like it in the State Capitol, used historical motifs to foster civic and national pride among viewers and in doing so, helped to codify a version of Wisconsin’s history that overlooked the complexities of its past.1

Several months after Ballin completed the murals, the commissioners decided to withhold their final payment because the paintings were “not entirely satisfactory.” The daughter of one of the historical characters portrayed in the murals, General Starkweather, criticized the likeness of her father, and similar critiques of historical inaccuracies were made of other historical figures represented, including Red Bird. They asked Ballin to return and work with the room’s interior decorator, Elmer Garnsey, to make alterations. When he did, Ballin chose to redo the entire painting of the Red Bird episode (above is the updated version) and remounted it on the wall. He also redid his portrait of Colonel Joseph Bailey, a Civil War hero, and his two paintings of the former state capitols buildings in Madison. Although Ballin refused the commissioners’ requests to alter other panels in a series of feisty exchanges, they were pleased with the revisions to the Red Bird panel. As was reviewer Ada Rainey, who commented that the “historical accuracy [of the murals] is excellent, and there is an impression of reality that the scenes depicted actually took place in the early life of Wisconsin.” The mural, and others like it in the State Capitol, used historical motifs to foster civic and national pride among viewers and in doing so, helped to codify a version of Wisconsin’s history that overlooked the complexities of its past.1

Image and Ballin's quotation from his pamphlet, "Mural Paintings in the Executive Chamber, State Capitol Building Madison, Wisconsin," (New York: 1913).

Details on the commissioner's response and Ballin's alterations from “Historic Structure Report” issued by the State of Wisconsin’s Department of Administration, Division of Facilities Development in 2004.

Rainey's quotation in The International Studio vol. 51, no. 204 (Feb., 1914).

| Previous page on path | Wisconsin State Capitol - Gallery, page 6 of 8 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Executive Chamber - Major Whistler Conferring with Red Bird"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...