Executive Chamber - Nicolet Meeting Wisconsin Indians in 1634

- In Ballin's Words

- Allegory and History

- Source/Citations

Ballin described his murals in a pamphlet published in 1913:

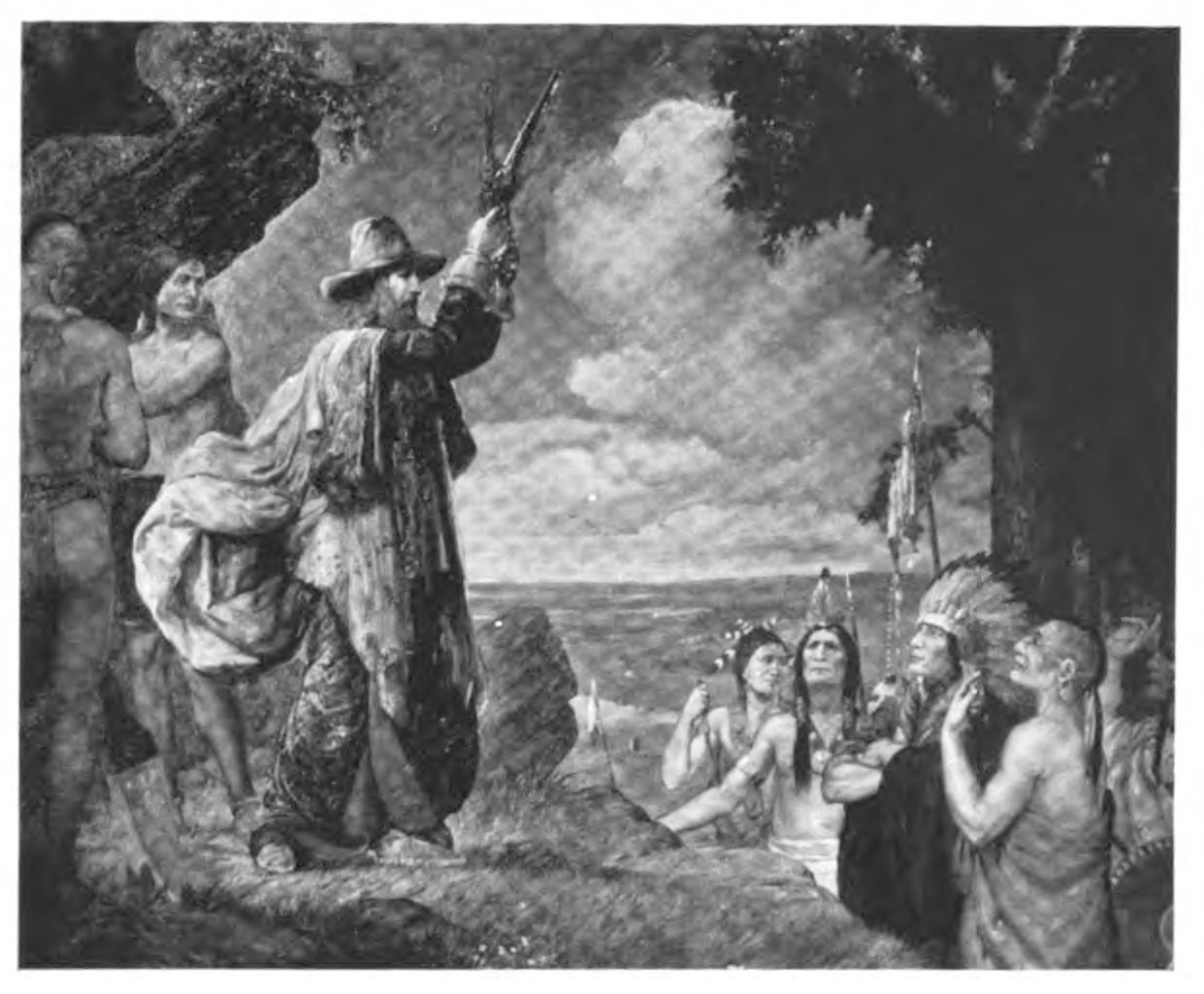

"Nicolet meeting Wisconsin Indians in 1634 and demonstrating the explosive property of powder. Jean Nicolet, son of a Parisian mail carrier, was the first white man to reach the western shore of Green Bay. little was known of the vast forests that lay west of Quebec, and for over 150 years after Columbus discovered the western hemisphere no white man ventured as far as Lake Michigan. The people who dwelt in the unexplored western land were known as the 'people of the sea.' These were the Wisconsin Winnebagoes. They had migrated to the lake country. Previous to reaching Green Bay, Nicolet was under the impression that these people were Chinese. During 1634 the Wisconsin tribes were in council. It is reported that Nicolet appeared before them in a mandarin's robe of state adorned with figures of flowers and birds. He approached with a pistol in each hand. The astonished natives styled him Thunder Beaver. He made friends with the Indians and encouraged them to visit Montreal."

"Nicolet meeting Wisconsin Indians in 1634 and demonstrating the explosive property of powder. Jean Nicolet, son of a Parisian mail carrier, was the first white man to reach the western shore of Green Bay. little was known of the vast forests that lay west of Quebec, and for over 150 years after Columbus discovered the western hemisphere no white man ventured as far as Lake Michigan. The people who dwelt in the unexplored western land were known as the 'people of the sea.' These were the Wisconsin Winnebagoes. They had migrated to the lake country. Previous to reaching Green Bay, Nicolet was under the impression that these people were Chinese. During 1634 the Wisconsin tribes were in council. It is reported that Nicolet appeared before them in a mandarin's robe of state adorned with figures of flowers and birds. He approached with a pistol in each hand. The astonished natives styled him Thunder Beaver. He made friends with the Indians and encouraged them to visit Montreal."

On the walls of the Executive Chamber, Ballin chose to depict historical rather than allegorical figures from Wisconsin's history. Positioned on the West Wall to the left of the entrance was a portrayal of Jean Nicolet, "the first white man to reach the western shore of Green Bay." Ballin had done extensive research for the piece and, after learning that Nicolet believed that by heading west he would eventually reach China, decided to depict him in an elaborate "yellow silk Chinese robe of state."1 The placid scene offered a triumphalist version of the encounters between Wisconsin's American settlers and its indigenous peoples that affirmed Anglo superiority and the legitimacy of Anglo American rule. The Indians here stand in shock fear of the awesome power of Nicolet's guns and their deference to him seems inevitable. In reality, Nicolet's arrival initiated almost two centuries of violent conflict as other European settlers slowly encroached into the Wisconsin territory and gradually displaced the indigenous population. The area was first colonized by the French and, after the War of 1812, the United States began to establish their control in the region, resulting in at least two wars with the native peoples of the region, the so-called Winnebago War of 1827 and the larger Black Hawk War of 1832, before Wisconsin became an American state in 1848. The episode had been depicted by Edwin Willard Deming in 1904, and by Franz Rohrbach in his mural in the Rotunda of the Brown County Courthouse in Green Bay in 1910, depicted below.

Franz Rohrback, "Jean Nicolet, landing at the Bay of Green Bay," 1910 |

Unfortunately for Ballin, in the eyes of some commissioners, the mural was "not entire satisfactory" in its representation of the Nicolet affair. When Ballin requested his final payment, the commissioners refused, citing specifically their displeasure with the Nicolet piece. Ballin insisted that it was “absolutely impossible to improve” the piece, telling the commissioners that he has consulted with “Indian expert” DeCost Smith who had affirmed the accuracy of the portrayal and found the painting “most convincing.” He even reached out to the Governor, Francis McGovern, who ignored his request for final payment. After months had passed and a new Governor was elected, Ballin contacted the commission again and in a defiant letter to the commission in 1915, Ballin defended his interpretation, reminding them that they had approved and accepted his original design and insisting that repainting the portrait of Nicolet would be costly. As he wrote:

“How are we to determine what Nicolet was like when he went into the then back-country, to show two pistols to a group of Indians who were not half surprised with Nicolet as was Nicolet with them. Any explorer confronted with a colossal miscalculation and receiving the impression of his fallacy through oriental needlework, would hardly care to meet a Winnebago face to face. I have gone into this very carefully and I feel that my interpretation is commendable, but if you desire to have Nicolet jumping out of a canoe, firing his two guns, which most likely did not explode the first time he tried, with a group of astonished Indians taking flight, it can be done. I do not believe it happened in this fashion. Each version is correct. Dramatically you are more so.”2

Ballin’s defiant tone only changed after he heard that Edwin Blashfield, one of the most famous artists of the Beaux Arts School who also contributed paintings to the Wisconsin State Capitol, had criticized his work. Almost two years after he had completed the original works, he offered to paint a more dramatic version of the encounter, but by that point, the commission had completed its charge and was disbanded.

The conflict over the mural of Nicolet revealed Ballin’s attitudes about art in the early years of his career. First, the episode showed that he, like other artists, had to reconcile his artistic visions with those of his patrons, often resulting in disagreements. Here the vision presented was of the state’s history, showing, that while they shared a concern for “accuracy,” Ballin and his commissioners had different ideas about how to represent the encounter between Nicolet and the Indians. Ballin’s stubborn defense of his historical accuracy and storytelling abilities suggests that he believed them to be defining characteristics of his work and, while he avoided any other similar conflicts in the years that followed, he continued to take pride in (and boast about) those qualities of his work. Second, that Ballin changed his mind about his work after hearing of Blashfield’s critique shows his admiration and respect for the leaders of the Beaux Arts movement, which seems to have been more important to him than pleasing the mural’s commissioners. Only the word of a true Master painter like himself could persuade him of the need to make alterations, reflecting Ballin’s elitist attitudes about art and culture in his early career.

Image and Ballin's quotation from his pamphlet, "Mural Paintings in the Executive Chamber, State Capitol Building Madison, Wisconsin," (New York: 1913).

1. Details on the commissioner's response and Ballin's alterations from “Historic Structure Report” issued by the State of Wisconsin’s Department of Administration, Division of Facilities Development in 2004, which can be viewed here.

2. ibid, p. 29.

| Previous page on path | Wisconsin State Capitol - Gallery, page 7 of 8 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Executive Chamber - Nicolet Meeting Wisconsin Indians in 1634"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...