Wards Comprised of Blocks

The wards were essentially self-sufficient, each including “a communal mess hall, recreation building, latrines, and laundry” (Ibid). Each block also had “recreation buildings used for offices, stores, canteens, a beauty parlor, [and] a barber shop" (AJA WWII Memorial Alliance). Effectively separated, the individual wards had limited communication, and therefore abilities to organize.

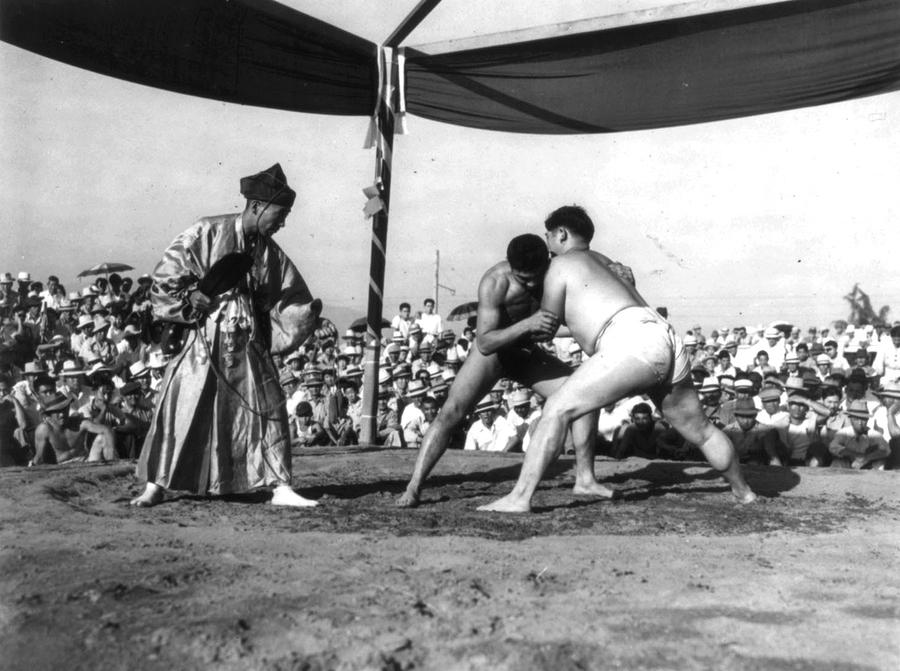

Additionally, the wards competed against each other in a “Talent Show,” where prizes were handed out to the most talented wards as decided by an all-white panel (Roxworthy, The Spectacle of Japanese American Trauma: Racial Performativity and World War II) . These talent shows not only quelled community between the wards, but served in oppressing the Japanese-Americans, further labeling them as racial aliens, though most of the detainees were second generation Nisei disconnected from their supposed Japanese heritage. Adhering to new modern ideas of criminals as capable of reform, inmates were mandated to perform with “numbers [that] must be Occidental,” and in many ways were also being mandated to “rehear[se] for American re-entry” (Ibid). These performances often were used to show an integration of cultures which “asserted the transnational community of [the] Japanese Americans” (Ibid). For example, a sumo wrestling match would be held and then subsequently an American softball game. However, these activities were less celebratory of Japanese Americans as seeking to degrade and antiquate Japanese cultures and “showcas[e] Americanized Cultural Performance” for photographers and journalists that visited the camp (Ibid). The performances ultimately emphasized the “foreignness of Japanese theatricality and its supposed permeation of everyday Japanese behavior” (Ibid).