Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder): Zalmen the Cobbler’s Bank Book (Zalmen Pt. 12)

Zalmen the Cobbler’s Bank Book (On his 80th Birthday) - (Zalmen dem shusters bank-bikhl)

from Zalmen the Cobbler: Chapters about his 70 years of Life in America (Zalmen der shuster: kapitlen vegn zayne zibtsik yor lebn in Amerike) by Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder). Los Angeles: Chaver-Paver Book Committee, 1955: 242-246.

Translated by Caroline Luce, edited by Hershl Hartman.

“And here I come to the end of my stories,” Zalmen the Cobbler said to me. “It seems to me that I’ve already told you the most interesting happenings in my life. What I will now tell you is about my bank book. Since I am soon turning eighty years old, I’m taking stock of the sum of my estate."

“If I go where every man must eventually go, at one hundred and twenty,” Zalmen said to me with a smile that was both bashful and clownish, “I will take with me to the heavens my bank book and show them the fortune that I accumulated on this sinful earth.”

“A bank book?” I supposedly wondered to myself, knowing very well that he meant something else.

But it really was a bank book, a common bank book. He handed it to me with a mischievous look through his shiny bright eyeglasses. I opened the first page and there was written a number, his name, and various dates of deposits to the sum of two hundred dollars. On the second page there were no deposits noted, but withdrawals, totaling the amount that left nothing to be taken out — and that ended the “account.”

On the third notebook and on the fourth, right up to the last page, were jotted down, in Zalmen’s handwriting, various dates and various calculations.

“When they ask me in that other world: ‘Zalmen, what did you accomplish on that sinful earth?’ I will say to them: ‘here, just take a look for yourselves. It is noted here: so many and so many thousands of pairs of shoes made in my life for people to wear, protecting them from wet and cold. And still more thousands of pairs I mended for those too poor to buy themselves new ones. So many thousands and thousands of leaflets and pamphlets distributed against the injustices in life. So, so many hundreds of friends collected in the course of my years in America. And I’m not even talking about all of my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren: good, useful people.

“Then I would point out in my bank book all the thousands of dollars that I spent on my son Elik, so that he could become a violinist. I started at fifty cents an hour to pay a teacher, and ended at twenty-five dollars an hour. Yes, it cost me all of twenty-five dollars a lesson for the last teacher here in Los Angeles, a music professor.

“And if they say to me in heaven: ‘Zalmen, isn’t it a luxury for a poor shoemaker to spend so much money to teach your son to play the violin? And a luxury, as you know, we consider to be among the sins.’ I will answer: ‘how can you, in heaven, say such a thing? You ought to be ashamed! Because as I understand it, a luxury is a thing you can live without. But how can the world live without music? I and my Goldie felt that is was a necessity. Such a talented child, leave him to the grace of God? And besides, what worth were the many thousands of dollars that I spent compared with the marvelous music that he now draws from his violin? And do you think it was that easy for me? I mean not only the money; I mean the hardship that my son, poor soul, suffered through all those years, practicing so many hours a day, while his friends played outdoors. Later, when he grew older, other friends were already independent — and he was still so dependent on his father the cobbler. It bothered him very much and often he had complained to me about why I hadn’t taught him a trade. By day and by night — he needed only to practice, locking himself in the bathroom late at night to practice there, so as not to disturb our slumber. You know nothing of that hardship... But now as a result, since he’s reached mastery, all that former suffering seems like nothing.’

“And what a joy for me, my Goldie, and his brothers and sisters, that from us has arisen a great master-teacher violinist! He’s now devoted to teaching, not to become rich, because for years and years he has taught at no cost a couple of children whose music will in time resound around the world, like a Mischa Elman or a Jascha Heifetz...”

And so Zalmen turned the pages in his bank book for me, lingering on each page, explaining the meaning of the figures that he had jotted down, until we came to the last page on which there was only one figure: that was two thousand. And then Zalmen’s face beamed and his high forehead reddened.

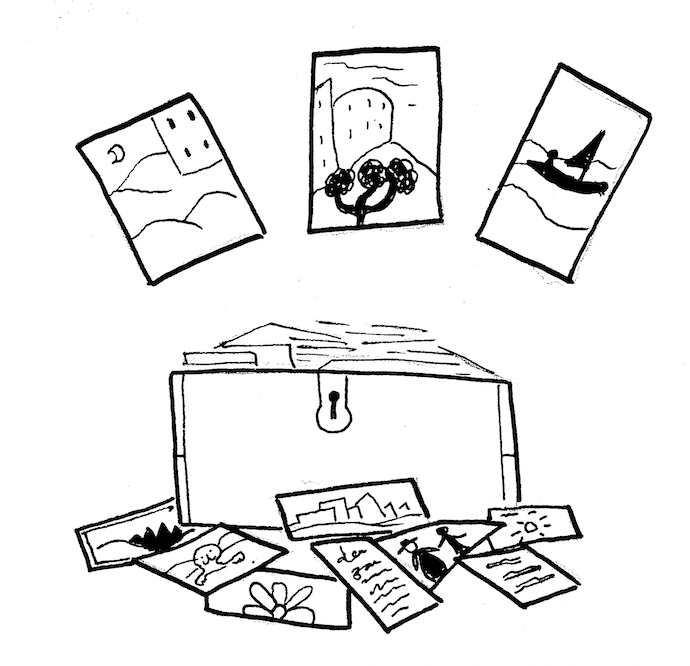

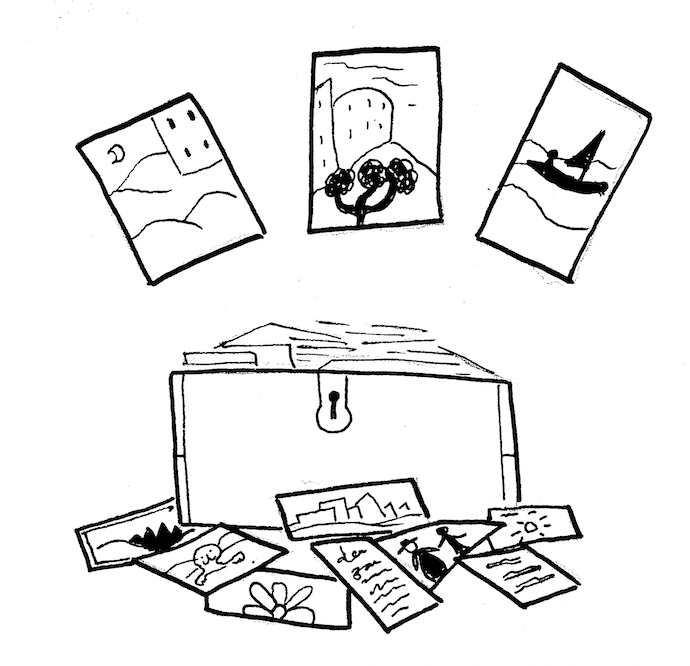

“That is the greatest capital that I saved up, real capital that can be touched.” And he went to a cabinet and took out a big box and handed it to me.

And in the box were two thousand little cards, picture postcards, that people send to to their families when they go on vacation to Niagara Falls, or the Grand Canyon, or to other famous notable places. And on those two thousand postcards, each of which bore a picture of a notable place, were messages on the reverse written not only by close friends, but also by his customers for whom he had mended or made shoes. He had collected the postcards over a period of forty years! There were some dated back to 1912. A customer of Zalmen’s, traveling on vacation, probably thought: “Let’s send a postcard to that interesting, friendly shoemaker, who is so pleasant to talk with.” There were even many postcards from Europe — from Paris, from Rome, from Switzerland, and Zalmen had preserved them all. And now he had all of two thousand of them.

And he also included the cards in his accounting of the good deeds in his bank book that he expects to take along to that other world.

“I will say to them there,” he said, half seriously, half mockingly, “other people accumulated houses, jewelry, and other material riches. I accumulated friends, all kinds of friends and among all kinds of peoples...and that means, to be sure, me and my Goldie. If they were to only permit me into heaven without my Goldie, I would say to them: ‘Thanks but no thanks! Without her, I won’t go!’”

I accumulated friends, all kinds of friends and among all kinds of peoples...and that means, to be sure, me and my Goldie. If they were to only permit me into heaven without my Goldie, I would say to them: ‘Thanks but no thanks! Without her, I won’t go!’”

And he really doesn’t go anywhere without her...everywhere, all smiles, people see them both. They enjoy their time with everyone until late into the night. And then on New Years people saw them both dancing. She, the seventy-eight year old and he, the eighty year old. And their dancing together inspired and uplifted people far more than if the greatest dance artists were to dance. It was a dance of a many years-old love between husband and wife. It was a dance of the joy and suffering of a sixty-year tightly bound married life...

Beautifully-rhythmic they danced. He, Zalmen with his straightly held back — or it seemed to him that his shoulders had straightened themselves and he was a young man of long ago — and she, a little heavy on her feet, a buxom woman, a blushing beauty, with a sort of hidden coquettishness, as in her young years...

from Zalmen the Cobbler: Chapters about his 70 years of Life in America (Zalmen der shuster: kapitlen vegn zayne zibtsik yor lebn in Amerike) by Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder). Los Angeles: Chaver-Paver Book Committee, 1955: 242-246.

Translated by Caroline Luce, edited by Hershl Hartman.

“And here I come to the end of my stories,” Zalmen the Cobbler said to me. “It seems to me that I’ve already told you the most interesting happenings in my life. What I will now tell you is about my bank book. Since I am soon turning eighty years old, I’m taking stock of the sum of my estate."

“If I go where every man must eventually go, at one hundred and twenty,” Zalmen said to me with a smile that was both bashful and clownish, “I will take with me to the heavens my bank book and show them the fortune that I accumulated on this sinful earth.”

“A bank book?” I supposedly wondered to myself, knowing very well that he meant something else.

But it really was a bank book, a common bank book. He handed it to me with a mischievous look through his shiny bright eyeglasses. I opened the first page and there was written a number, his name, and various dates of deposits to the sum of two hundred dollars. On the second page there were no deposits noted, but withdrawals, totaling the amount that left nothing to be taken out — and that ended the “account.”

On the third notebook and on the fourth, right up to the last page, were jotted down, in Zalmen’s handwriting, various dates and various calculations.

“When they ask me in that other world: ‘Zalmen, what did you accomplish on that sinful earth?’ I will say to them: ‘here, just take a look for yourselves. It is noted here: so many and so many thousands of pairs of shoes made in my life for people to wear, protecting them from wet and cold. And still more thousands of pairs I mended for those too poor to buy themselves new ones. So many thousands and thousands of leaflets and pamphlets distributed against the injustices in life. So, so many hundreds of friends collected in the course of my years in America. And I’m not even talking about all of my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren: good, useful people.

“Then I would point out in my bank book all the thousands of dollars that I spent on my son Elik, so that he could become a violinist. I started at fifty cents an hour to pay a teacher, and ended at twenty-five dollars an hour. Yes, it cost me all of twenty-five dollars a lesson for the last teacher here in Los Angeles, a music professor.

“And if they say to me in heaven: ‘Zalmen, isn’t it a luxury for a poor shoemaker to spend so much money to teach your son to play the violin? And a luxury, as you know, we consider to be among the sins.’ I will answer: ‘how can you, in heaven, say such a thing? You ought to be ashamed! Because as I understand it, a luxury is a thing you can live without. But how can the world live without music? I and my Goldie felt that is was a necessity. Such a talented child, leave him to the grace of God? And besides, what worth were the many thousands of dollars that I spent compared with the marvelous music that he now draws from his violin? And do you think it was that easy for me? I mean not only the money; I mean the hardship that my son, poor soul, suffered through all those years, practicing so many hours a day, while his friends played outdoors. Later, when he grew older, other friends were already independent — and he was still so dependent on his father the cobbler. It bothered him very much and often he had complained to me about why I hadn’t taught him a trade. By day and by night — he needed only to practice, locking himself in the bathroom late at night to practice there, so as not to disturb our slumber. You know nothing of that hardship... But now as a result, since he’s reached mastery, all that former suffering seems like nothing.’

“And what a joy for me, my Goldie, and his brothers and sisters, that from us has arisen a great master-teacher violinist! He’s now devoted to teaching, not to become rich, because for years and years he has taught at no cost a couple of children whose music will in time resound around the world, like a Mischa Elman or a Jascha Heifetz...”

And so Zalmen turned the pages in his bank book for me, lingering on each page, explaining the meaning of the figures that he had jotted down, until we came to the last page on which there was only one figure: that was two thousand. And then Zalmen’s face beamed and his high forehead reddened.

“That is the greatest capital that I saved up, real capital that can be touched.” And he went to a cabinet and took out a big box and handed it to me.

And in the box were two thousand little cards, picture postcards, that people send to to their families when they go on vacation to Niagara Falls, or the Grand Canyon, or to other famous notable places. And on those two thousand postcards, each of which bore a picture of a notable place, were messages on the reverse written not only by close friends, but also by his customers for whom he had mended or made shoes. He had collected the postcards over a period of forty years! There were some dated back to 1912. A customer of Zalmen’s, traveling on vacation, probably thought: “Let’s send a postcard to that interesting, friendly shoemaker, who is so pleasant to talk with.” There were even many postcards from Europe — from Paris, from Rome, from Switzerland, and Zalmen had preserved them all. And now he had all of two thousand of them.

And he also included the cards in his accounting of the good deeds in his bank book that he expects to take along to that other world.

“I will say to them there,” he said, half seriously, half mockingly, “other people accumulated houses, jewelry, and other material riches.

I accumulated friends, all kinds of friends and among all kinds of peoples...and that means, to be sure, me and my Goldie. If they were to only permit me into heaven without my Goldie, I would say to them: ‘Thanks but no thanks! Without her, I won’t go!’”

I accumulated friends, all kinds of friends and among all kinds of peoples...and that means, to be sure, me and my Goldie. If they were to only permit me into heaven without my Goldie, I would say to them: ‘Thanks but no thanks! Without her, I won’t go!’”And he really doesn’t go anywhere without her...everywhere, all smiles, people see them both. They enjoy their time with everyone until late into the night. And then on New Years people saw them both dancing. She, the seventy-eight year old and he, the eighty year old. And their dancing together inspired and uplifted people far more than if the greatest dance artists were to dance. It was a dance of a many years-old love between husband and wife. It was a dance of the joy and suffering of a sixty-year tightly bound married life...

Beautifully-rhythmic they danced. He, Zalmen with his straightly held back — or it seemed to him that his shoulders had straightened themselves and he was a young man of long ago — and she, a little heavy on her feet, a buxom woman, a blushing beauty, with a sort of hidden coquettishness, as in her young years...

| Previous page on path | Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder), page 12 of 13 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Chaver Paver (Gershon Einbinder): Zalmen the Cobbler’s Bank Book (Zalmen Pt. 12)"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...