Shen Zhou, Solitary Angler on an Autumn River, 1492

1 2016-12-16T06:30:49-08:00 Nancy Um 4051576cc4fc4011fb0706d1c68e5004e7744d2d 13915 13 plain 2017-02-28T11:07:51-08:00 Seattle Art Museum 1492 Handscroll Ink on paper Ming dynasty (1368-1644) China 97.80 97.80_01cc.jpg Gift of Karen Wang Shen Zhou Overall: 13 9/16 x 411 7/16in. (34.4 x 1045 cm) Image: (1) Frontispiece: 30 cm (h) x 83.8 cm (w) (2) Title label: 23.5 cm (h) x 1.7 cm (w) (3) Painting proper: 28.9 cm (h) x 60.4 cm (w) (4) Colophon paper (w/ calligraphy): 29.1 cm (h) x 760.8 cm (w) (5) Colophon paper (blank): 30.1 cm (h) x 26.5 cm (w) Seattle Art Museum Digital Imaging Dept. Image Copyrighted © Seattle Art Museum, 2008 Marcia Focht 4935999cee56888348b83668dd2c85f8c1267824This page has paths:

- 1 2017-02-07T10:04:22-08:00 Lauren Cesiro f37e4e52c3d9a4ff08b7937020ee9048f11c6739 Shen Zhou, Solitary Angler on an Autumn River, 1492 (Media Gallery) Nancy Um 9 Image, details, and screenshot gallery 2017-02-24T13:13:46-08:00 Nancy Um 4051576cc4fc4011fb0706d1c68e5004e7744d2d

This page is referenced by:

-

1

media/ZhouDetail2.jpg

media/97.81_01cc.jpg

2016-12-16T05:04:14-08:00

Presentation and Interface

183

plain

2017-06-20T18:54:36-07:00

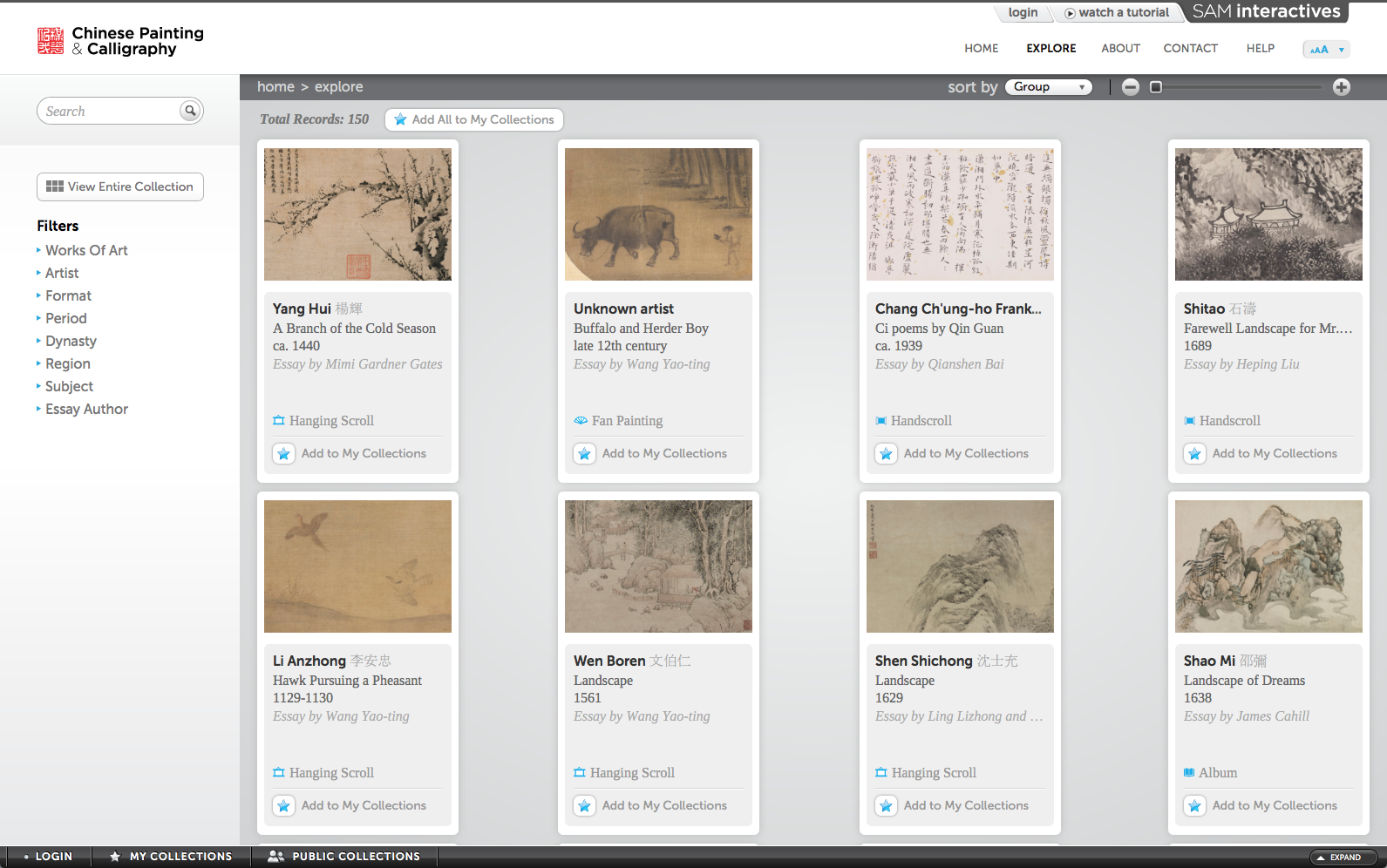

Landing on the home page, the visitor is invited directly into the collection, which is displayed in a slide-table format. ♦Thumbnail images preview the works, which can be filtered through a ♦sidebar on the left according to a number of criteria: group, date, region, artist, and essay author, among others. Along the bottom of the window is a ♦hidden menu through which visitors may create an account, curate their own collections of images, and share these collections publicly if they so choose. This is also where one registers as a "scholar," the initial stage of approval by SAM curators that eventually makes it possible to submit an essay for review.

Selecting an individual work takes the visitor into a viewer interface that enables close examination of the image and its accreted elements—inscriptions, seals, and colophons, particularly, but in many cases, mountings as well. A large, open palette displaying the image in its entirety extends across the browser window, while to the right, a sidebar, hidden by default, contains the catalog information, scholarly essays, and other curatorial data. One can zoom in on the chosen image through a variety of means; an inset navigator window helps keep track of where you are in the original composition. Depending on the quality of the digitization, the level of available detail is remarkable, in the best cases providing a clear understanding of the brushwork, subtleties of ink washes, and texture of the paper or silk support—even a sense of the restorations and repairs to the artwork.

Clicking on the sidebar from its default hidden position causes it to extend out into or, more precisely, over the main viewing window. Among the sidebar options are tombstone data; inscriptions and seals; a scholarly essay, if one exists for the selected artwork; a list of related works in SAM’s collection; publication and exhibition histories; a bibliography; and two unusual categories for a scholarly catalog: “questions for thought,” generally posed by the curator of Chinese Art at SAM then, Josh Yiu, and a public comments section.

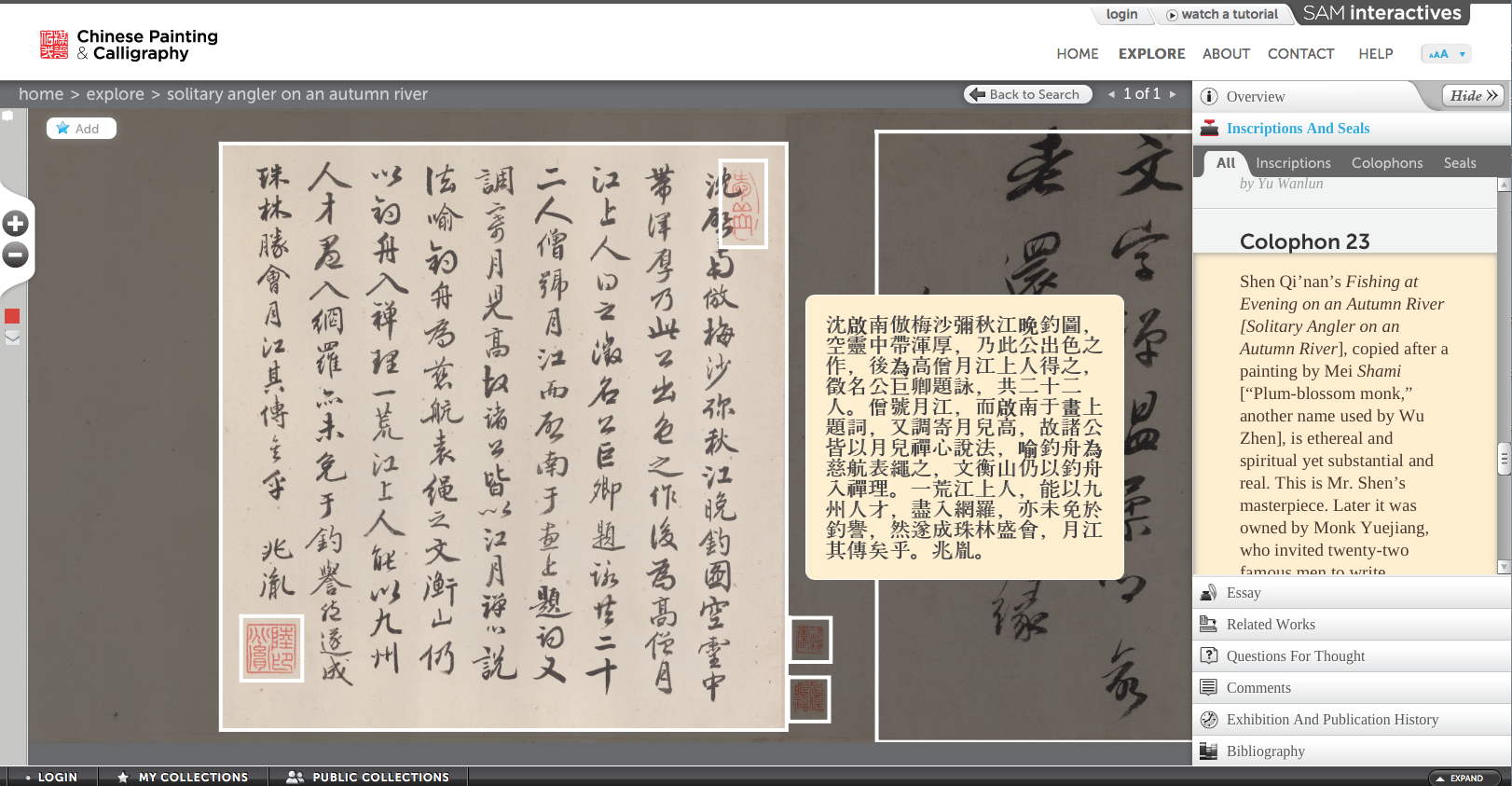

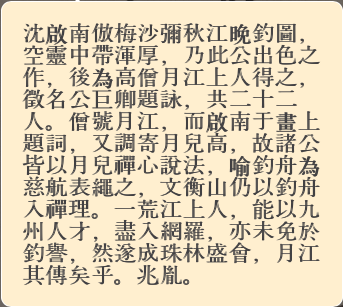

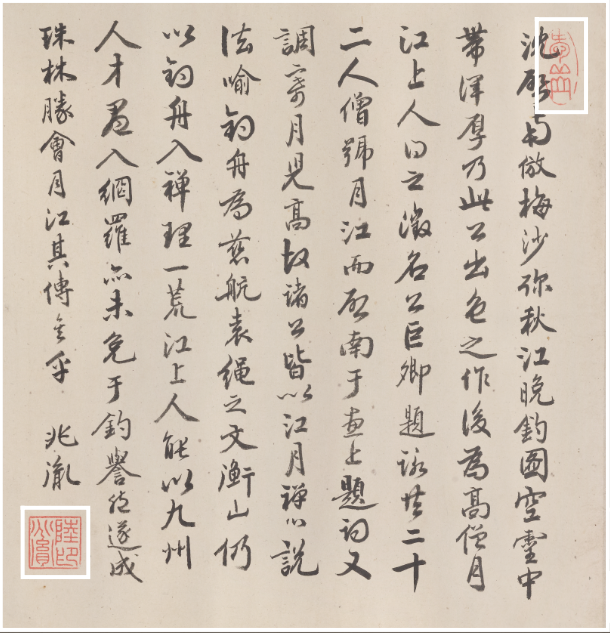

Perhaps the most useful section for researchers, and the one of greatest interest for demonstrating aspects of the site’s interactivity, contains a list of translations and transliterations of each work’s various inscriptions and impressed seals. When opened in the sidebar, the targeted elements become highlighted in the image itself by a series of white boxes. Selecting an ♦inscription or seal in either place takes you to the corresponding item in the other. A floating window in the main viewing panel provides a ♦transcription of the Chinese text, a highly useful feature even for fluent readers of Chinese, as different calligraphic forms are often difficult to decipher, especially when stamped from a carved seal; ♦translations of inscriptions and transcriptions of seals then appear in the sidebar.

The potential utility of this section remains somewhat unfulfilled by incomplete data, however, even for objects in Groups 1 and 2. While a transcription of the seal is of great help, it is equally important to know who the seal belonged to, as owners often employed obscure alternative names in their seals. This information is supplied in some cases, but it is not in many others, even when the accompanying essay or general knowledge makes it clear that the seal owner’s identity is known. For both seals and inscriptions, references to standard seal dictionaries, which were likely consulted during the course of research, would be a great boon, as would citations to major biographical dictionaries; equally important, cases in which the seal owner cannot be identified or such references are unavailable could likewise be noted.[3]

The presentation of the works is thus decidedly object-centric and strongly reflects the visuality and materiality of Chinese painting. This is perhaps most evident when comparing the SAM site to other OSCI interfaces. Most online scholarly catalogs are essentially text-centric, imitating to a greater or lesser degree the format of a printed page. The National Gallery of Art’s seventeenth-century Dutch paintings site might be the most explicit in this regard. As the latest, updated edition of an established print catalog, the layout of the individual digital entries, which features the focus image at the top of a text page, closely imitates that of its analog predecessor.[4] The Art Institute of Chicago, by contrast, strikes something of a balance between text and image while retaining the essential appearance of a print publication. In its catalog of paintings and drawings by Gustave Caillebotte, for instance, which is oriented largely around the artist’s 1877 Paris Street; Rainy Day, the layout remains essentially that of an exhibition catalog, with images set into text.[5] All the artworks discussed in the essay are constantly available through a sidebar, however, while the key image sits in the upper-right corner for quick reference. Furthermore, readers can click directly into an image set within the text at any time, as well as utilize a variety of interactive viewers, such as access to ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray photographs taken during conservation.

SAM’s design places the object literally front and center; the default portal is an object/image viewer whose primary functionality involves navigating and interacting with the image. Text of all types is initially hidden, and even when opened, it remains simply formatted. Thus, the user gains direct access to the work of art in a manner that is ultimately sensitive to the ways in which a viewer of the actual painting or piece of calligraphy would interact with it. Beginning with an overall perspective, one is then able to examine the surface of the image in extraordinary detail. It is not the same as seeing the actual work, to be sure, but it also has its advantages, offering hypernatural levels of visibility that can reveal subtleties in individual strokes that are all but impossible to perceive with the naked eye. For a field of art historical study that still relies heavily on the connoisseurship of brushwork and materials, this is an especially welcome capacity. Indeed, in light of these strengths, I wished for a full-screen mode in order to explore the image without the distraction of other aspects of the navigational interface, a feature that would be of particular benefit when teaching with the site.

The cleanly designed sidebar balances accessibility of information with the primacy of the object. When open, it is narrow enough to create a side-by-side viewing experience. As one reads the catalog essays, this makes it easy to compare details of visual description and argument with the image directly, moving around and zooming in as needed. Although not every essay relies equally on visual argumentation, for those that do—such as Wang Yao-ting’s discussion of Buffalo and Herder Boy, a small fan painting that, based on compositional and stylistic elements, he attributes to the late twelfth century—the capacity to view both the text and an image detail simultaneously is a distinct advantage. It is unfortunate, therefore, that the open sidebar extends over the image, rather than adaptively resizing the viewer window to accommodate both text and the full image on the screen. While this did not pose a problem on a larger desktop screen, on a smaller screen, such as a laptop, certain portions of the image became inaccessible, obscured by the sidebar. Several other technical problems also crop up: surprisingly, the online catalog does not function properly on tablets, which seems a major limitation as such touch-screen devices become more prevalent;[6] URLs for individual works are extraordinarily long and do not always redirect properly when pasted into hyperlinks; and movement back and forth between the slide-table view and specific works eventually leads to problems with navigation, forcing the user back out to the home page.

Throughout the entire catalog, the design also encourages the exploration of text-image relations. The presence of often extensive writing, both directly on the surface of the work of art in the forms of inscriptions and seals and appended to it by way of a frontispiece and/or colophons, is a distinctive element of East Asian painting. These texts may date to the time of the object’s creation or to its later reception and are essential not only to understanding the work itself but also to the process of viewing and experiencing it. Despite the importance of these textual mediations, Chinese paintings are generally cropped for reproduction to present only the image, omitting the often numerous accompanying colophons that evidence its many lives. Inscriptions found directly on the painting are frequently left untranslated and unanalyzed, although they are literally integral to the image field. Seals are rarely reproduced in detail, rendering them entirely illegible. By transcribing and translating all the inscriptions found on works of art in Groups 1 and 2, SAM’s publication allows the contemporary viewer to engage with this information in much the same manner that a viewer of the actual work would have—piece by piece, while looking at it as a whole. Moreover, the importance of these complex intertextual and transtemporal relations is reinforced and expanded on in many of the essays, whether focused on the primary inscription(s), as in Richard Barnhart’s consideration of a short handscroll by Shen Zhou, Solitary Angler on an Autumn River (1492), or on the colophons, as in Zaixin Hong’s treatment of River Landscape after Four Masters (1624), by the late Ming painter Lan Ying. The care and attention given to inscriptions constitute a distinct boon not only to researchers but also to more casual viewers, for whom the textual aspects of Chinese painting are too often inaccessible.

Background image:

Shen Zhou, Solitary Angler on an Autumn River, 1492 (detail of inkwash)

Source: Seattle Art Museum -

1

media/97.81_01cc.jpg

media/56.50.1_01cc.jpg

2016-12-16T05:05:04-08:00

Essays and content

61

plain

2017-06-21T08:09:02-07:00

Of perhaps broader interest to many visitors are the scholarly essays that accompany the objects in Groups 1 and 2, as well as those SAM invites for works in Group 3. Formatted for the sidebar, they appear as long, narrow documents when opened. Footnotes are viewed in a floating window by hovering over the highlighted superscript number, while comparative images are embedded as thumbnails within the text that can be opened in a separate window; unfortunately, when clicked on during preparation of this review, the larger versions of these images returned error messages saying they were unavailable.

The essays examining the eighteen works in Group 1 are by well-established scholars of Chinese art who take a range of approaches, from the connoisseurial to the sociohistorical. The catalog opens with Gates’s engaging essay on Yang Hui’s delicate depiction of flowering plum, A Branch of the Cold Season (ca. 1440). It serves as an excellent introductory text, as Gates considers the significance of the painting as a gift and effectively interprets the way in which the inscribed poem and image act together to create the meaning of the painting. She concludes her essay with a technical discussion of connoisseurship and dating, working in detail with the many seals that are impressed on the handscroll.

Similarly, Qianshen Bai takes up a long calligraphic handscroll by Chang Ch’ung-ho Frankel, an important but little-studied female calligrapher and painter of the twentieth century, several of whose works are in SAM’s collection. As is his hallmark, Bai makes calligraphy accessible to the lay reader, clearly describing its forms and techniques as he interweaves biography and style. Of special interest is his insight that there is something “musical” in Frankel’s small, neat “standard script.” Bai’s beautiful development of this idea through his discussion of character form is let down only by the reader’s inability to readily identify the specific characters to which he is referring; one wishes that the same white boxes used to highlight inscriptions and seals might also have been employed to tag the details mentioned in this and other essays.[7]

Less connoisseurially-based essays are equally satisfying. Michele Alberto Matteini’s study of an eighteenth-century album by the artists Luo Ping and Xiang Jun offers a wonderful meditation on collaboration and the master-pupil relationship in Chinese painting. Heping Liu identifies a short handscroll by Shitao, Farewell Landscape for Mr. Wuweng (1689), as the second of a trio recording the seventeenth-century master’s later-life trip to Beijing, and thus part of a key moment in the painter’s personal journey in a period of political and social tumult. Breathing new life into the familiar subject of painting in the style of old masters, Barnhart explores significations of copying in Zhou’s Solitary Angler on an Autumn River, whose pictorial reflection on the “inkplay” of the Yuan master Wu Zhen served as a vehicle for self-discovery and expression.

Together, the essays in Groups 1 and 2 present rich, varied perspectives on the collection that are generally well pitched to both specialist researchers and general readers. For the latter, this range has the advantage of demonstrating the different methodologies and approaches engaged by scholars of Chinese painting and calligraphy, including some that are quite specific to East Asian art. At the same time, those with more targeted interests may find this diffuseness distracting, as there is no standard selection of data that all the essays seek to provide; they are in this sense more truly individual essays than scholarly catalog entries. This concern could be symptomatic of a broader issue: the publication as a whole, and several of the essays in particular, would have benefited from more rigorous editing. In some cases, this is reflected in stylistic or structural issues—certain essays need further refinement of argument and expression. In other cases, however, it is simply a matter of copyediting, with persistent errors as basic as repeated sentences, misnumbered footnotes, and inconsistent or missing information. For example, the biographical data surrounding seals, mentioned above, ranges from fairly robust to entirely missing, while something as straightforward as artists’ life dates, which oddly are omitted from the tombstone information, are only occasionally found in the essay itself.

Beyond these top works, the majority of the collection—one hundred pieces, encompassing some of great potential interest—are categorized in Groups 3 and 4. Photographs of these objects, though displayed as in Groups 1 and 2, are not always of the same quality in terms of resolution, the inclusion of additional inscriptions, or the mounting. Group 3 comprises paintings and calligraphy that SAM judges to be worthy of further research. Although the museum claims that the works in Group 4 are of lesser importance and are included only for the sake of comprehensiveness, they, too, represent an important contribution: here are the lower-market productions and outright fakes of the collection, objects that ought to be of significant interest in the connoisseurially oriented discipline of Chinese art history. Their publication as part of the online scholarly catalog runs counter to generations of museological practice that has tended to bury copies, forgeries, and more pedestrian compositions as unworthy of art historical study, rather than as integral parts of the visual past.

Group 3 highlights the inherent potential of the digital scholarly catalog for progressive publication and public participation in scholarship. SAM explicitly invites contributions to this group from users, in the form of short essays, though presumably transcriptions of seals and inscriptions, biographical information on artists, and other incremental pieces of research would also be welcomed. This group provides an extraordinary opportunity, especially for young researchers, as it contains a number of works that are every bit as interesting and important as those in Groups 1 and 2: for instance, three works from the Qing court, including a collaboratively produced mid-eighteenth-century history painting, an imperial patent from the last years of the dynasty, and a fan by the court artist Shen Zhenlin that was probably intended as an imperial gift;[8] landscapes in a variety of formats attributed to a number of important late Ming and Qing artists, among them Hongren’s Plum Blossom and Rocks from the seventeenth century, a small untitled fan by Sung Maojin (1619), and an eighteenth-century album of paintings after past masters by Huang Ding; and a rich selection of modern works spanning the twentieth century, such as Lan Yinding’s fascinating 1955 album Sketches of Life in Formosa and a monumental scene of riverine industry from 1971 by Zong Qixiang. Even brief examinations reveal compelling art historical questions in each of these works, and in many others, and they offer significant opportunities not only to researchers but also to instructors interested in problem-based approaches to teaching.

Background image:

Shitao, Farewell Landscape for Mr. Wuweng, 1689 (detail of brushwork)

Source: Seattle Art Museum