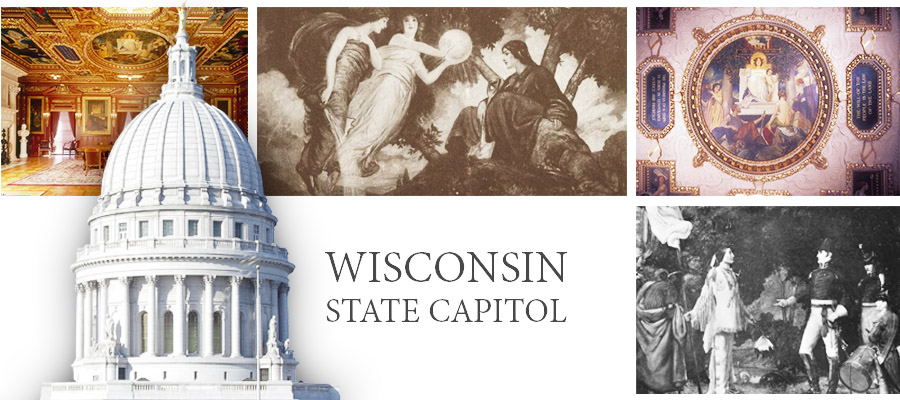

Wisconsin State Capitol 2.0

- Beaux Arts Prodigy

- About this Commission

- Gallery

- Sources/Citations

Beaux Arts Prodigy: Arts Education and Early Career

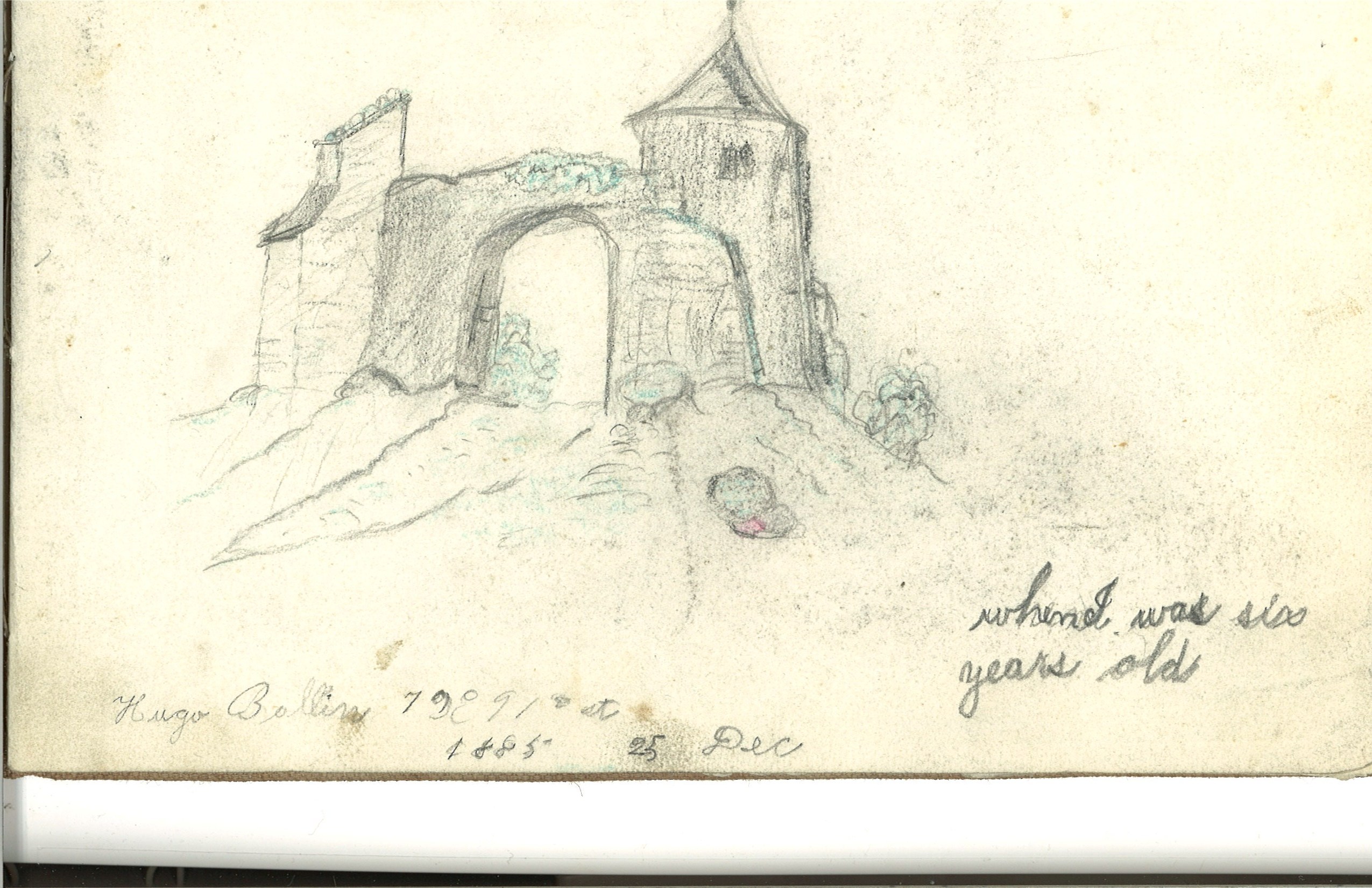

Ballin's Childhood Sketchbook c. 1885, UCLA Special Collections |

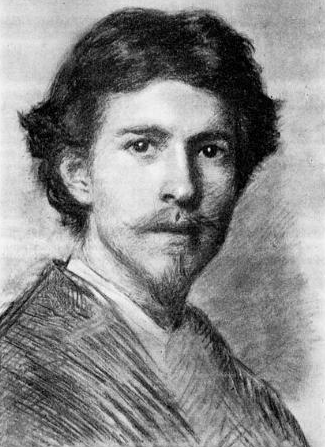

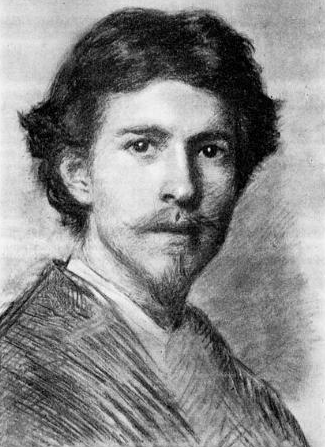

Wyatt Eaton, Self Portrait, 1879, National Gallery of Canada |

Murals, Mendelssohn Music Hall, Brooklyn Museum |

FROM UCLA |

Sibylla Europa (1906), Smithsonian American Art Museum |

The Lesson (1907), Smithsonian American Art Museum |

Mabel Ballin, Photoplay, 1921. WikiMedia Commons. |

FROM UCLA |

The decorative art included in Capitol in Madison reflected a stylistic shift among American artists of the Beaux-Arts school, described by art historian Bailey Van Hook in her book, The Virgin and the Dynamo. Although European-educated artists of Wyatt Eaton’s generation worked to foster an "American Renaissance," they didn't always agree about how exactly to forge a distinctly American style. Ballin, like his mentors Eaton and Blum, believed in emulating and preserving the traditional forms and techniques of the European masters. But replicating these strategies was also limiting and an increasing number of younger American artists who were closer in age to Ballin opted to experiment with new forms and techniques. These artists, also educated in Europe, sought to capture the dynamic changes occurring in American society in the age industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. To establish a more “modern” American style in mural painting, they replaced allegory with history: instead of using idealized, female figures to serve as symbols in their paintings, they opted for more realistic, masculine figures to represent characters from American history. They featured “real” events, rather than ancient legends, relating stories that would educate the American public about the country's history, cultivate patriotism and assert a proud, American nationalism. As Bailey Van Hook argued, replacing idealized female figures (virgins) with modern, dynamic masculine ones (dynamos) reflected a shift from idealism to modernism emerging among American artists that was part of their efforts to forge a uniquely American national style.8

Ballin's murals at the Wisconsin State Capitol captured his personal quest to reconcile his love for classicism with this emerging trend in American mural art. In the fifty-two figures that appear in the pieces he designed for the Executive Chamber, he incorporated both allegorical symbols and real, historical figures to tell his version of Wisconsin's history. The duality of the murals was captured in the space: the allegorical paintings were placed on the ceiling of the room, while the historical paintings lined the walls. The largest painting in the room, “Unity after the Civil War making Peace,” blended the two styles together, embodying Ballin's efforts to position himself as a leader of his generation of American artists.

The Wisconsin State Capitol (1906-1917)

Court of Honor and Grand Basin, 1893, WikiMedia Commons |

Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, 1893, WikiMedia Commons |

Wisconsin’s former State Capitol was built during the Civil War, but had burned to the ground after a gas leak during the winter of 1904. Two years later, the State hired architect George B. Post, a veteran of the Columbia Exposition, to design a replacement. Post had a degree in civil engineering from New York University and studied architecture in the studio of Richard Morris Hunt, the first American architect to attend L’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. After working on several buildings in New York in the 1880s, including the New York Stock Exchange Building and the New York Cotton Exchange Building, Post was recruited to design the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building at the Columbia Exposition. He designed a massive structure that was over 230 feet tall and 1,600 feet long and housed over 40 acres of exhibition space, making it the largest enclosed space ever built. Post also commissioned several muralists to decorate the domes of the building, helping to making mural decoration a popular feature of Beaux Arts architecture in its “golden age.”

Wisconsin State Capitol, 2004, Wisconsin State Journal |

The Capitol Building in Madison that Post designed was equally ornate and grandiose. Echoing the nation’s capitol, Post’s structure featured a large central dome positioned at the intersection of four building wings extending to the north, south, east and west, with entrances at both the southeast and northwest axes. Like his building in the White City, the structure was massive: it rose almost three hundred feet tall, just three feet shorter than the nation’s capitol, and contained over 400,000 square feet of space. It was assembled out of forty-three types of stone from six countries and eight states, including white granite from Vermont on the exterior of the building and the dome and granites from Wisconsin in the hallways of lower three floors. It took more than a decade to complete the Capitol and cost the state $7.25 million total, but it continues to serve as monument to the virtues of democracy and the strength and power of the State.

Daniel Chester French “Wisconsin” (1914), WikiMedia Commons |

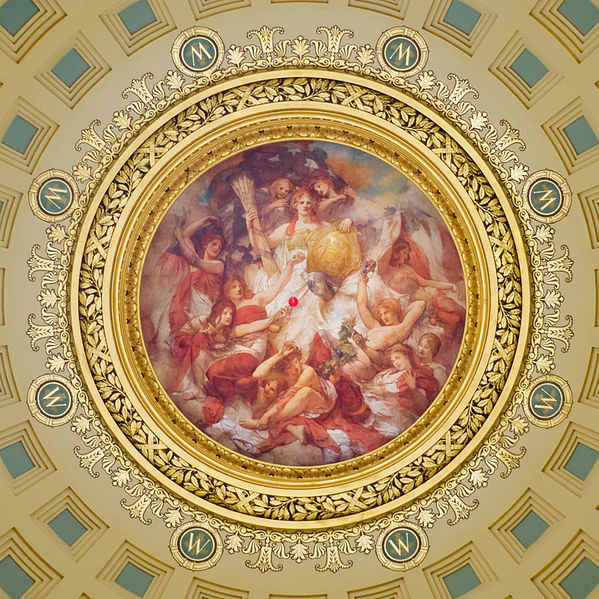

Post recruited colleagues he had worked with on the Columbian Exposition to design decorations for the building to complement its mission, including Daniel Chester French, Kenyon Cox, and Edwin Howland Blashfield. Jean Francois Millet, a longtime instructor at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts, was to serve as the director of decoration and contribute works of his own, but died on the Titanic en route. But despite his absence, all of the artists stayed true to Beaux Arts ideals: each artist created individual works that beautified the space and utilized Renaissance-inspired imagery to engender the ideals of civic responsibility, good government and State pride, complementing the mission of Post’s design. On the pediment of the west wing of the building, for example, Viennese-educated sculptor Karl Bitter created a piece entitled “Unveiling the Resources of the State” which featured a large Romanesque female figure to represent the State surrounded by figures symbolizing the state’s natural resources. In his sculpture for the top of the dome, Daniel Chester French similarly represented the state as an enrobed female figure, pointing off into the distance in reference to the state’s motto, “Forward.” Edwin Blashfield’s tondo, “The Resources of Wisconsin,” which decorated the top of the rotunda, took the imagery even further by featuring a woman wrapped in weathered American flag surrounded by diaphanous female figures holding the state’s biggest exports. All three works used allegorical, female figures to represent the values the artists believed to be fundamental to Wisconsin’s success and democratic society more broadly.

Blashfield, “The Resources of Wisconsin” (1914), WikiMedia Commons |

Other murals in the Capitol Building, by contrast, employed historical motifs and included real characters and events from American history rather than symbolic female ones. Albert Herter painted a series of murals for the Supreme Court Hearing Room that offered a history of the evolution of the law, including scenes from the Roman courts, the signing of the Constitution and disputes over sovereignty in the earliest days of American settlement in Wisconsin. Charles Yardley Turner’s murals in a hearing room on the North wing similarly featured pastoral scenes of Native Americans and colonists from Wisconsin’s past as well as “A Modern Transportation Scene” showcasing a vibrant harbor, railroad lines and automobiles. As art historian Bailey Van Hook described, these historical motifs reflected a desire among some American artists to move away from the classical, Beaux Arts style and forge a distinct, national American style in mural art that would capture the dynamic changes occurring in American society at the time.10

Albert Herter, Supreme Court Hearing Room Murals (1915), wisconsin.gov |

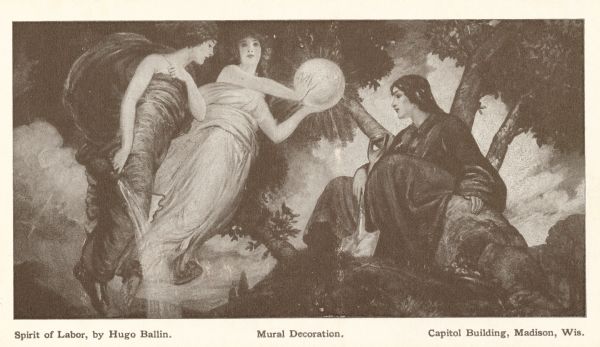

Executive Chamber, 1915, Wisconsin Historical Society |

Hugo Ballin received the commission to design the murals in the Executive Chamber after the artists originally chosen to paint them, Jean Francois Millet, died on the Titanic. The commission came after much of the building and its art had already been completed, allowing Ballin to model his designs off of those of the other, older and more experienced artists. In doing so, he fused the two styles that prevailed, combining allegorical and historical motifs in his works. On the ceiling, he echoed the works of Bitter, French and Blashfield by portraying “The Spirit of Wisconsin” as an enrobed, female figure and using other symbolic, mostly female, figures to represent the “Virtues” of the state: agriculture, mining and lumber, commerce, the arts, wisdom, labor, charity, justice and religious tolerance. On the walls of the Chamber, he featured famous characters and episodes in Wisconsin’s history painted in a more realistic style, including Jean Nicolet’s arrival at Green Bay in 1634, Major Whistler accepting peace from Red Bird after the so-called “Winnebago War” of 1827, and a portrait of Joseph Bailey, Colonel of the Wisconsin Cavalry Regiment in the Civil War. In the largest panel on the South wall of the room titled “Unity Making Peace After The Civil War,” Ballin incorporated both motifs, representing “Unity” as an angelic female figure standing between famous characters from Wisconsin’s history. By blending history and allegory, Ballin's murals at the Wisconsin State Capitol captured his personal quest to reconcile his love for classicism with the emerging American style of mural painting.

Executive Chamber, North and West Walls, Wisconsin Historical Society |

Unfortunately for Ballin, his fusion was not well received by the murals’ commissioners. Their critiques were described in a letter to Ballin from the projects’ leaders:

“The universal opinion among those who have expressed themselves is that your work on the ceiling is unsurpassed, that your paintings on either side of the mantel are most beautiful and that the pictures of the Surrender of Redbird and Lapham are all that they should be. The rest are regarded as unfortunate. Whether or not this is because of the choice of subject, in the execution, or in the conception of what the pictures should portray, I am not able to state.”

Ballin did not take the criticism lightly and returned to Madison a few months later to make the desired repairs and corrections. But he also defended his choices and refused to change some elements of his work and, by doing so, revealed his attitudes about art, history and representation in the early days of his career.

TITLE HERE

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Early Career

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Early Career

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Early Career

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Early Career

Executive Chamber, "Labor and the Spirits of Rain and Sunshine"

Executive Chamber, North and East Wall

Executive Chamber, North and West Wall

Executive Chamber, South and West Wall

Executive Chamber, West Wall

Citations and Additional Resources

For additional information on the art and architecture of the Wisconsin State Capitol Building, click here to view the “Historic Structure Report” issued by the State of Wisconsin’s Department of Administration, Division of Facilities Development in 2004. Additional information for this page provided by Bailey Van Hook, The Virgin and the Dynamo: Public Murals in American Architecture, 1893-1917, (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2003). 1. Kramer, William M., “Hugo Ballin, Artist and Director,” in ed. Shalom Saber, Steven Fine and William M. Kramer, A Crown for a King: Studies in Jewish Art, History and Archaeology (Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House Ltd., 2000), p. 161. 2. Van Hook, Bailey, The Virgin and the Dynamo: Public Murals in American Architecture, 1893-1917 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2003), p. xvii. Details on Eaton’s life come from “Dictionary of Canadian Biography – Wyatt Eaton –accessed at http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eaton_wyatt_12E.html. 3. Details from an untitled, undated clipping that appears in a scrapbook, Hugo Ballin Papers, Department of Special Collections, Charles Young Library, UCLA, Box 29, Folder 2. 4. Quote “pre-Raphaelite” from an untitled, undated clipping that appears in a scrapbook, Hugo Ballin Papers, UCLA, Box 29, folder 2; Quotation from coverage of Ballin’s exhibition in Buffalo (c. 1909), scrapbook, Hugo Ballin Papers, UCLA, Box 29, Folder 2. 5. Quotation from “Hugo Ballin” by H. St. G. unknown date, scrapbook, Hugo Ballin Papers, UCLA, Box 29, Folder 2. According to the painting’s current owners, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, its full title is “Sibylla Europa Prophesying the Massacre of the Innocents” (1909). 6. Ballin articulated these ideals in response to statements made by sculptor Gutzon Borglum who claimed U.S. Sculptors were “devoid of high creative ideas.” His response was recounted in a forum called “American Art -- From Different Points of View” that appeared in the New York Times Oct. 11th, 1908 and a clipping of an article entitled “Borglum Charges Divide Art Circles” by an unknown author on the same page of a scrapbook housed in the Hugo Ballin papers, UCLA Box 29, Folder 2. Ballin’s “determination to get some element of pure decorative beauty into every picture that he paints…” was noted in another review that appears in the scrapbook from an unknown author written Feb. 28th, 1911. 7. "Wife’s Beauty Adds Charm to Artist’s Pictures” New York Herald (c. 1910), scrapbook, Hugo Ballin Papers, UCLA, Box 29, Folder 2 8. Van Hook, The Virgin and the Dynamo, p. xx. 9. Van Hook, The Virgin and the Dynamo, p. 44. 10. Van Hook, The Virgin and the Dynamo, p. xx. |

Discussion of "Wisconsin State Capitol 2.0"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...