Tsui Asakawa

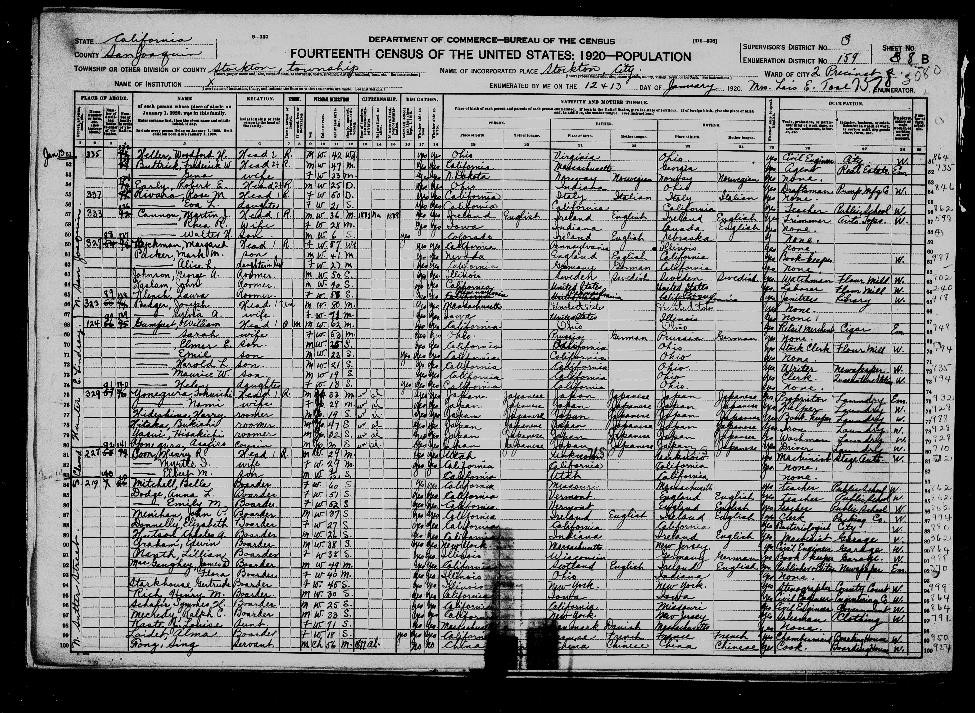

I was surprised to see Asian immigrants holding humanities jobs at this particular point in time. I feel as though it has always been stressed to me how immigrants tried to fill the most vital, unwanted jobs that they could because they needed to make money in anyway. But the Asakawas lived with an artist, a photographer, and a journalist. That’s very unique and got me a bit off track in my original focus of laundry and cooking as popular jobs for Asian immigrants. But, thinking more about it, that makes perfect sense. Japanese food was becoming fashionable and trendy, and so was Japanese culture, at least before the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924. That’s why Japanese food was so desired; it seemed foreign, but not so foreign that the general American populous couldn’t relate to it. It seems that the logical next step for a fascination with their food would be a fascination with their culture. Japanese art was very much in style, so having a successful Japanese visual artist makes sense. It doesn’t specify what medium the artist used most. It also doesn’t specify what type of photography is done by the photographer, so I don’t know if it’s commercial or for artistic purposes as well. The most surprising to me, though, is that a Japanese man was a journalist for a newspaper in 1920. Goichi Yamane was 52 at the time of the census, and I’m just very surprised that people accepted the idea of a Japanese reporter. Perhaps it wasn’t well-known that this was his profession, or maybe he never had to sign his name. Either way, it seems odd that this man could have been reporting on the very news that was preventing the rest of his country from entering the United States (Year: 1920).

That is really all of the information I could find about Tsui. The documents were few and far between, which leads me to believe that she may not have lived long. I also couldn’t find anything further about her daughter or husband, or the people that she lived with. In terms of telling her story, I didn’t get a lot of information, but I learned a lot about the restaurant industry and how Japanese and Chinese food became so popular in the United States.