Chvonne's Reading and Thinking Notes 10/14

Ball, Cheryl E. “Designerly ≠ Readerly: Re-assessing Multimodal and New Media Rubrics for Use in Writing Studies.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 12.4 (2006): 393-412. Print.

In this article, Ball argues that the rubrics from Kress and Leeuwen’s multimodal discourse and Manovich’s Language of New Media, respectively, allow for an analysis in designedly ways but not readerly ways. Students in writing studies cannot “sufficiently analyze new media texts.” The rubrics of the aforementioned authors “have not yet addressed rhetorical situations of design.” Ball presents that Kress and Leeuwen’s four strata aid in discussing “design process of a text.” She goes on to say that Manovich’s five principles of new media are “a technological checklist for whether a text is new media or not” (394). Ball argues that what is really needed is “a middle ground: a way for writing teachers to help students interpret all the modes of communication (as well as the designedly process) in a new media text” (394). To argue for readerly ways of analysis, Ball presents the connections between multimodal theory and designedly strategy and new media theory and designedly strategy. She analyzes a multimodal text using both rubrics. The analysis shows how each rubric helps with identifying modes and technologies, but not rhetorical aspects of the text. Ball identifies the New London Group as providing a foundation for multimodal theory. New London Group’s work on multiliteracies argued for the integration of multimodal text analysis and production in writing. The New London Group identified six modes of communication: linguistic, audio, spatial, gestural, visual, and multimodal (qtd in Ball 395). The New London Group introduced the language of design to writing studies teachers. This was a familiar area because the designing process is very similar to the revision process in writing.

Kress and Leeuwen’s work continued this work by providing a way to teach students how to read and analyze multimodal texts. Kress and Leeuwen provided four strata—discourse, design, production, and distraction—to help readers under the design process. Discourse refers to the idea that designers “start from what they know,” design is the strata where “a designer fulfills rhetorical or aesthetic situation by choosing appropriate and available modes and media to sue in a multimodal text.” Production strata refers to the “choice of modes that can be accommodated in a particular medium, and distribution refers too “how to get the text to readers” (396). Ball argues that these strata can help readers identify the materials of design but “do not address how or why a designer chooses specific modes or elements when creating that text” (396).

Manovich’s five principles of new media—numerical representation, modularity, automation, variability, and transcoding—provide a way for readers to identify that texts meet the requirements to be considered new media objects. Ball argues that these principles help a reader identify “the technical and technological aspects of digital new media, they do not offer a language with which a reader can rhetorically interpret that text.” (402). Ball captures my greatest concern after reading Manovich’s Language of New Media. I am relatively new to new media. Manovich presented these principles as inherent to new media, which made me feel that I should be able to quickly identify them because they are obvious elements of new media. However, as Ball presents, “If a reader is not familiar with the technological conventions used in a text, Manovich’s principles have little relevant for that person” (402). Without some knowledge the technological aspects a “reader my not even be able to apply Manovich’s five principles, to determine whether a text is new media or not..”( 402).

Ball goes on to present her readerly approach, which utilizes a “generative-analysis model.” Ball uses familiar literary and rhetorical strategies to examine the multimodal text. This approach is more useful to writing studies because it address rhetorical (readerly ways) and technological and designedly ways. Ball analyzes the text in sequence pointing out the rhetorical moves and the connections between the technological and design elements and how these work together to make meaning. The key take-away is that the multimodal rubric and the new media rubric are not useful for readers who are new to new media or reads “who struggle with interpreting a new media text in relation to that text’s purpose” (410). A “generative, multi-angled reading” is needed to aid these beginning and inexperienced readers. It is also useful for helping teachers connecting “the meaning of multiple modes in a new media text to its purpose.” Ball’s article is a call for writing studies teachers to work on making connections between new media theories and writing theories that will work for writing teachers and students.

New Learning Chapter 7: Knowledge and Learning

This chapter of New Learning focused on the nature of knowledge and the connections between knowledge and learning. The chapter broke down the different ways of knowing and the connecting learning and education strategies. Knowledge is a combination of what’s inside and what’s outside. These areas are interconnected to the point that “knowledge is everywhere, always and at once inside and outside an individuals mental an corporeal space” (219). Learning is “the process of coming to know” (219). The chapter presents three ways of knowing: committed knowledge, knowledge relativism, and knowledge repertoires.

The Committed knowledge group focuses on one way of making knowledge. Examples of committed knowledge are religious truths, empirical truths, rationalist truths, and canonical truths. This way of knowing centers on the belief in the “superiority of their methods and the truthfulness of their representations” (222). The ways of knowing in this area focused on following particular methods or inherited truths. I was particularly interested in how committed ways of knowing are more exclusionary and that they all rely deeply on canonical knowledge. This way of knowing is definitely connected to social and class issues. This can also be seen in the sites of learning where special groups have authority. Knowledge moves from the “institutions of knowledge creation, via a knowledge transmission system that includes education, to a broader society that absorbs that knowledge.” (230). This works for those who are given access to the knowledge transmission systems.

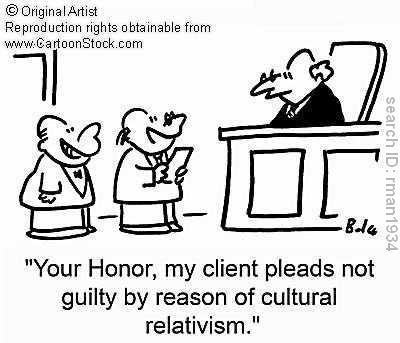

A key part of knowledge relativism is skepticism. This group of ways of knowing “are less certain about their own rightness” (230). Examples of this type of knowing are epistemological relativism, cultural relativism, and postmodernism. Epistemological relativism has less certainty, meaning “whatever you think you know is only every relative to your experiences, your interests, and your perspectives” (231). Everything known is relative to the individual and their perspective. Cultural relativism takes the position that “everything is relative to a cultural context at a historical moment” (233). For cultural relativist, what is known comes from experiences and feelings. There is a lot of weight placed on being authentic and true to one’s self. Postmodernism is in opposition to modernism. This way of knowing “incorporates elements of epistemological relativism and cultural relativism” (235). There is no single worldview or way of knowing. There are “lots of shreds and patches that happen to fall together as knowledge” (236).

Knowledge repertoires are about creating a repertoire of different “knowledge processes” (238). This is a process wherein you “select, mix, match, and test different knowledge-making approaches developed by various kinds of committed knowledge.” Balance is found by questioning and challenging the absolute truths of committed knowledge with “a measure of knowledge relativism” (238). The ways of engagement with knowing are: experiencing, conceptualizing, analyzing, and applying. These four ways of engagement each have to processes or “kinds of things you can do to know” (241). Experience is broken into experiencing the known and experiencing the new. Conceptualizing consist of conceptualizing by naming and conceptualizing with theory. Analysis consists of analyzing functionally and analyzing critically. Applying knowledge consists of applying appropriately and applying creatively. The ways of knowing in this knowledge repertoire focuses on collaborative learning. The sites of learning are more varied because there are “more people as active knowledge makers” (254).

Keywords (pages 254-255)

Experiencing the known: “reflecting on one’s own experiences, interests and perspectives”

Experiencing the new: “observing the unfamiliar, immersing oneself in new situations, reading and recording new facts and data”

Conceptualizing by naming: “developing categories and defining terms”

Conceptualizing with theory: “putting the key terms together into theirs and making generalizations”

Analyzing functionally: “analyzing logical connections, cause and effect, structure and function”

Analyzing critically: “evaluating critically your own and other people’s perspectives, interests, and motives”

Applying appropriately: “applying insights to real-world situations and testing their validity”

Applying creatively: “making an intervention in the world that is innovative and creative”

Reflection:

This weeks readings made me think of the dissertation process, especially the section on knowledge processes. The processes outlined in New Learning are very similar to the process of dissertating from the experiencing the known to applying creatively. I enjoyed this chapter because it forced me to think about the ways of knowing that I value. I realized as I often do that my ways of knowing are often at odds with the status quo. I am, and always have been, against the idea of a canon. I disliked most of the books I was required to read in High School. I understand the concept or the need for a canon, but I think it reinforces ideologies that we need to move past and beyond.

In regards to Ball's article, I was able to breathe a sigh of relief. I had Manovich's text for the canonical text project. I disliked the text immensely because I did not think it was for those interested in new media beyond techies and designers. I did not understand or connect with many of the concepts/ideas presented in the text. I did not see how the five principles were useful beyond helping one debate whether or not something is new media. After that, then what? I like the idea that design and reading are not equal. They are two different things, but they both need to be addressed. I think writing studies has a long way to go in addressing texts in designerly and readerly ways because we are still debating about what is "new" in new media and deciding on multiliteracies, mutliple rhetorics, and the place of writing studies in academia in general. It would be great to tackle one problem at a time, but we must work on ALL the things.

In this article, Ball argues that the rubrics from Kress and Leeuwen’s multimodal discourse and Manovich’s Language of New Media, respectively, allow for an analysis in designedly ways but not readerly ways. Students in writing studies cannot “sufficiently analyze new media texts.” The rubrics of the aforementioned authors “have not yet addressed rhetorical situations of design.” Ball presents that Kress and Leeuwen’s four strata aid in discussing “design process of a text.” She goes on to say that Manovich’s five principles of new media are “a technological checklist for whether a text is new media or not” (394). Ball argues that what is really needed is “a middle ground: a way for writing teachers to help students interpret all the modes of communication (as well as the designedly process) in a new media text” (394). To argue for readerly ways of analysis, Ball presents the connections between multimodal theory and designedly strategy and new media theory and designedly strategy. She analyzes a multimodal text using both rubrics. The analysis shows how each rubric helps with identifying modes and technologies, but not rhetorical aspects of the text. Ball identifies the New London Group as providing a foundation for multimodal theory. New London Group’s work on multiliteracies argued for the integration of multimodal text analysis and production in writing. The New London Group identified six modes of communication: linguistic, audio, spatial, gestural, visual, and multimodal (qtd in Ball 395). The New London Group introduced the language of design to writing studies teachers. This was a familiar area because the designing process is very similar to the revision process in writing.

Kress and Leeuwen’s work continued this work by providing a way to teach students how to read and analyze multimodal texts. Kress and Leeuwen provided four strata—discourse, design, production, and distraction—to help readers under the design process. Discourse refers to the idea that designers “start from what they know,” design is the strata where “a designer fulfills rhetorical or aesthetic situation by choosing appropriate and available modes and media to sue in a multimodal text.” Production strata refers to the “choice of modes that can be accommodated in a particular medium, and distribution refers too “how to get the text to readers” (396). Ball argues that these strata can help readers identify the materials of design but “do not address how or why a designer chooses specific modes or elements when creating that text” (396).

Manovich’s five principles of new media—numerical representation, modularity, automation, variability, and transcoding—provide a way for readers to identify that texts meet the requirements to be considered new media objects. Ball argues that these principles help a reader identify “the technical and technological aspects of digital new media, they do not offer a language with which a reader can rhetorically interpret that text.” (402). Ball captures my greatest concern after reading Manovich’s Language of New Media. I am relatively new to new media. Manovich presented these principles as inherent to new media, which made me feel that I should be able to quickly identify them because they are obvious elements of new media. However, as Ball presents, “If a reader is not familiar with the technological conventions used in a text, Manovich’s principles have little relevant for that person” (402). Without some knowledge the technological aspects a “reader my not even be able to apply Manovich’s five principles, to determine whether a text is new media or not..”( 402).

Ball goes on to present her readerly approach, which utilizes a “generative-analysis model.” Ball uses familiar literary and rhetorical strategies to examine the multimodal text. This approach is more useful to writing studies because it address rhetorical (readerly ways) and technological and designedly ways. Ball analyzes the text in sequence pointing out the rhetorical moves and the connections between the technological and design elements and how these work together to make meaning. The key take-away is that the multimodal rubric and the new media rubric are not useful for readers who are new to new media or reads “who struggle with interpreting a new media text in relation to that text’s purpose” (410). A “generative, multi-angled reading” is needed to aid these beginning and inexperienced readers. It is also useful for helping teachers connecting “the meaning of multiple modes in a new media text to its purpose.” Ball’s article is a call for writing studies teachers to work on making connections between new media theories and writing theories that will work for writing teachers and students.

New Learning Chapter 7: Knowledge and Learning

This chapter of New Learning focused on the nature of knowledge and the connections between knowledge and learning. The chapter broke down the different ways of knowing and the connecting learning and education strategies. Knowledge is a combination of what’s inside and what’s outside. These areas are interconnected to the point that “knowledge is everywhere, always and at once inside and outside an individuals mental an corporeal space” (219). Learning is “the process of coming to know” (219). The chapter presents three ways of knowing: committed knowledge, knowledge relativism, and knowledge repertoires.

The Committed knowledge group focuses on one way of making knowledge. Examples of committed knowledge are religious truths, empirical truths, rationalist truths, and canonical truths. This way of knowing centers on the belief in the “superiority of their methods and the truthfulness of their representations” (222). The ways of knowing in this area focused on following particular methods or inherited truths. I was particularly interested in how committed ways of knowing are more exclusionary and that they all rely deeply on canonical knowledge. This way of knowing is definitely connected to social and class issues. This can also be seen in the sites of learning where special groups have authority. Knowledge moves from the “institutions of knowledge creation, via a knowledge transmission system that includes education, to a broader society that absorbs that knowledge.” (230). This works for those who are given access to the knowledge transmission systems.

A key part of knowledge relativism is skepticism. This group of ways of knowing “are less certain about their own rightness” (230). Examples of this type of knowing are epistemological relativism, cultural relativism, and postmodernism. Epistemological relativism has less certainty, meaning “whatever you think you know is only every relative to your experiences, your interests, and your perspectives” (231). Everything known is relative to the individual and their perspective. Cultural relativism takes the position that “everything is relative to a cultural context at a historical moment” (233). For cultural relativist, what is known comes from experiences and feelings. There is a lot of weight placed on being authentic and true to one’s self. Postmodernism is in opposition to modernism. This way of knowing “incorporates elements of epistemological relativism and cultural relativism” (235). There is no single worldview or way of knowing. There are “lots of shreds and patches that happen to fall together as knowledge” (236).

Knowledge repertoires are about creating a repertoire of different “knowledge processes” (238). This is a process wherein you “select, mix, match, and test different knowledge-making approaches developed by various kinds of committed knowledge.” Balance is found by questioning and challenging the absolute truths of committed knowledge with “a measure of knowledge relativism” (238). The ways of engagement with knowing are: experiencing, conceptualizing, analyzing, and applying. These four ways of engagement each have to processes or “kinds of things you can do to know” (241). Experience is broken into experiencing the known and experiencing the new. Conceptualizing consist of conceptualizing by naming and conceptualizing with theory. Analysis consists of analyzing functionally and analyzing critically. Applying knowledge consists of applying appropriately and applying creatively. The ways of knowing in this knowledge repertoire focuses on collaborative learning. The sites of learning are more varied because there are “more people as active knowledge makers” (254).

Keywords (pages 254-255)

Experiencing the known: “reflecting on one’s own experiences, interests and perspectives”

Experiencing the new: “observing the unfamiliar, immersing oneself in new situations, reading and recording new facts and data”

Conceptualizing by naming: “developing categories and defining terms”

Conceptualizing with theory: “putting the key terms together into theirs and making generalizations”

Analyzing functionally: “analyzing logical connections, cause and effect, structure and function”

Analyzing critically: “evaluating critically your own and other people’s perspectives, interests, and motives”

Applying appropriately: “applying insights to real-world situations and testing their validity”

Applying creatively: “making an intervention in the world that is innovative and creative”

Reflection:

This weeks readings made me think of the dissertation process, especially the section on knowledge processes. The processes outlined in New Learning are very similar to the process of dissertating from the experiencing the known to applying creatively. I enjoyed this chapter because it forced me to think about the ways of knowing that I value. I realized as I often do that my ways of knowing are often at odds with the status quo. I am, and always have been, against the idea of a canon. I disliked most of the books I was required to read in High School. I understand the concept or the need for a canon, but I think it reinforces ideologies that we need to move past and beyond.

In regards to Ball's article, I was able to breathe a sigh of relief. I had Manovich's text for the canonical text project. I disliked the text immensely because I did not think it was for those interested in new media beyond techies and designers. I did not understand or connect with many of the concepts/ideas presented in the text. I did not see how the five principles were useful beyond helping one debate whether or not something is new media. After that, then what? I like the idea that design and reading are not equal. They are two different things, but they both need to be addressed. I think writing studies has a long way to go in addressing texts in designerly and readerly ways because we are still debating about what is "new" in new media and deciding on multiliteracies, mutliple rhetorics, and the place of writing studies in academia in general. It would be great to tackle one problem at a time, but we must work on ALL the things.

| Previous page on path | Chvonne Parker Bio, page 14 of 24 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Chvonne's Reading and Thinking Notes 10/14"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...