Floor Map

Public warm-up with Boris Charmatz

CloseA bras le corps

CloseLevee des conflits (solos, visitor’s version)

CloseAdrenaline: a dance floor for everyone and expo zero

Close

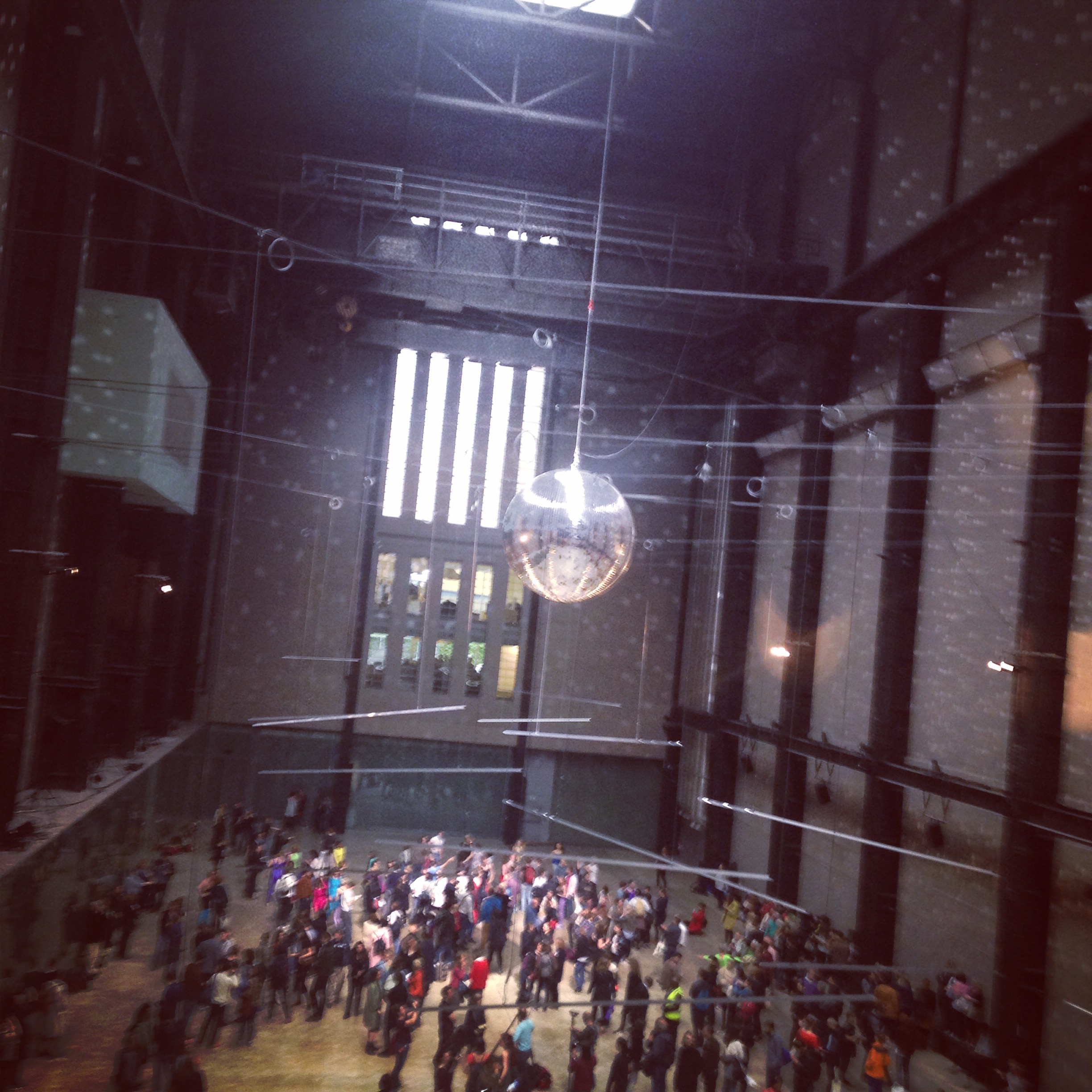

Adrénaline: A Dance Floor for Everyone and expo zero, an open disco hour reminiscent of a pop-up dance club, emerged twice a day at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, under a shimmering giant disco ball. Led by the enticing sets of DJ Oneman and DJ Jonjo Jury, respectively, this event was undoubtedly democratic and welcoming, fulfilling the premise of a communal celebration of the act of dancing. (I write about Saturday, May 16, 2015, which featured DJ Oneman during the first Adrénaline hour [5:15 pm–6:15 pm] and DJ Jonjo Jury [6:45 pm–8:15 pm] at the second, longer section of it. On May 15, the same timetable also featured DJ Oneman’s hour first, but the later slot was DJ Nathan G. Wilkins’s set.) As arguably the least structured part of the program, it also functioned as a moment of respite for all participants, and as a reset opportunity in the midst of a variety of choreographed inter/activities.

Having participated in one day-cycle of the weekend event, and having exchanged impressions with friends in attendance, I came to the conclusion that one’s perception of If Tate Modern Was Musée de la Danse? was contingent upon one’s participation in Adrénaline. Those who stayed felt more positively toward the entire event than those who did not. In some sense, then, Adrénaline was the glue that could amalgamate the heterogeneous events programmed by Boris Charmatz. Yet, the notion of Adrénaline as a coagulator seems inherently alien to the porous nature of this dancing interval. A dialectic emerged from the ambiguity of Adrénaline’s nature as a “non-event” relative to the choreographically induced act of dancing. ...Continue Reading

Roman Photo

Close

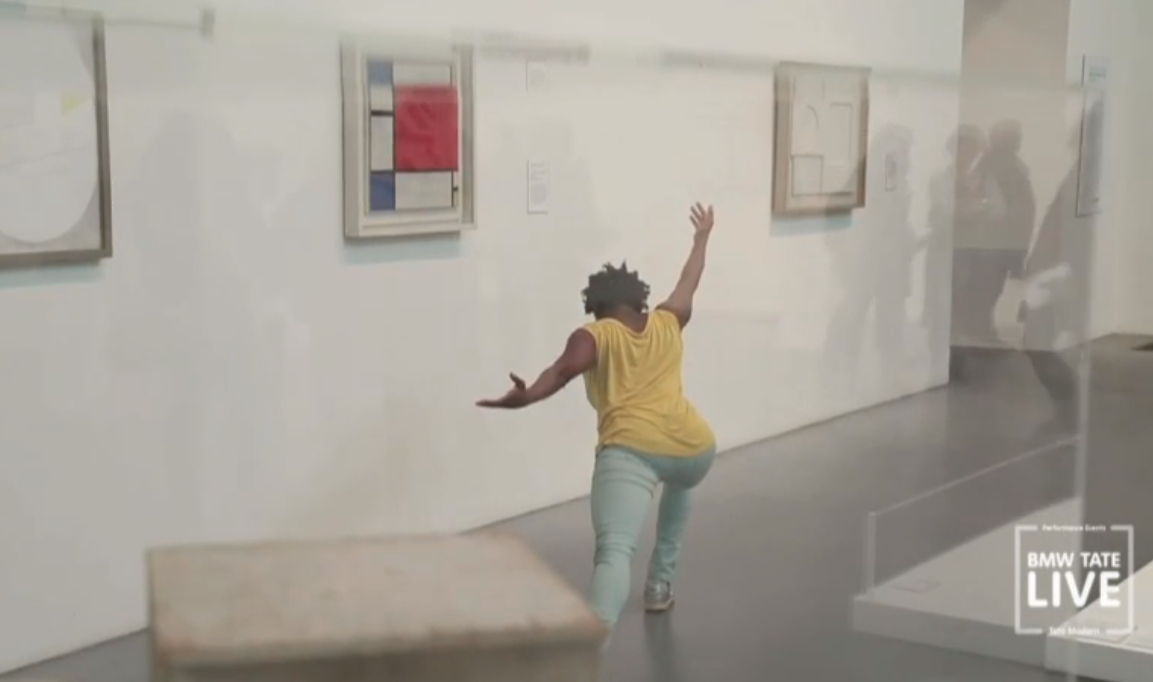

expo zéro

Closeexpo zéro was described on the online event page as “an exhibition project without any objects” and a meeting place for a diverse group of ten international performance and dance artists and scholars who were invited to “discuss, enact and perform” their proposals for a “museum of dance.” In this sense, the event was envisioned as a hub for the overarching concept of Charmatz’s museum of dance. The gathering was situated in a collection of unmarked white-box galleries. The dynamics of each meeting and room were distinctive. Popping into one would lead to an encounter with British performance artist Tim Etchells, who performed delicious walkabout soliloquies; contemporary Thai dance artist Pichet Klunchun, in another, was quiet and withdrawn into slow-motion movement introspections. Although discrete, because it was a bit tucked away from the other events, expo zéro functioned as a kind of viaduct that indirectly helped the visitor to transverse back and forth between the surrounding ideas on offer both in the Turbine Hall and by the dancers scattered in galleries throughout the building.

Like Adrénaline, expo zéro manifested a state of in-betweenness. In both, viewers and participants saw Charmatz giving up a certain degree of control, inviting chance and exploration into the project; both projects also relinquished the museum/dance binary in favor of hybrid forms. Given the vaguely anthropological tone of Charmatz’s experimentation with the museum, it is perhaps not surprising that the liminal spaces emerging in these two parts of his work might be theorized by the concepts proposed by anthropologist Victor Turner, who studied ritual structures in relation to individuals and communities: although in this case not people but places, the suspended states of both Adrénaline and expo zéro are “at once no longer classified and not yet classified” (Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols, Ithaca: Cornell University Press,1967, 96). This liminal dimension has ontological implications, as it equally negates “all positive structural assertions,” while it is “in some sense the source of them all” (97). Charmatz’s two events were also suspended realms of “possibility whence novel configurations of ideas and relations may arise” (ibid.).

Charmatz’s proposals crack open existing structures—the museum, the theater—that have traditionally hosted the relationships and encounters of these forms (art and dance, respectively). Particularly, perhaps, the thinking spaces of expo zéro help us to see that the answer might be in the very interrogation of the governing principles and conventions for museum and theaters. By keeping this process open, some new relational configurations between dance and the visual concept of art museum might be revealed.

Museum Metaphysics: 20 Dancers for the XX Century and Dance’s Ontology in the Museum

Close

The version of 20 Dancers for the XX Century in If Tate Modern Was Musée de la Danse? featured twenty dancers, each of whom represented different traditions, choreographers, and styles of dance, from the balletic tradition of George Balanchine to the contemporary street style of krumping. Dispersed throughout Tate Modern’s permanent collection galleries, the dancers, equipped with boomboxes, were free to choose the location, or “stage,” in which to perform their movement. Some, like Seguette, situated themselves in galleries, thus juxtaposing their piece of the twentieth century with the artistic styles surrounding them; others chose to perform in more apparently neutral or transitional spaces, such as hallways. ...Continue Reading

Title Here

CloseUnauthorized Performance in the Turbine Hall

CloseAs I watched this movement in the Turbine Hall from the perspective of Level Three above, I noticed that alongside the “authorized” or planned performances, people also danced uninvited. On the day I attended, to my observation, these uninvited dancers usually were children. Performing solos, duos, and in little ensembles, they danced in the open stretches and at the peripheries of the hall, creating spontaneous choreographies.

They ran, tumbled, and generally let loose through the expanse. Sometimes interested in the authorized dances, but often not, these unofficial performers made a place for their “work” in the Turbine Hall, enacting Tate’s institutional idea that this environment exists, according to its website, as a “place for people.” ...Continue Reading

Title Here

CloseTitle Here

CloseTitle Here

Closemanger (dispersed)

Close

This page has paths:

- Cover Francisco Millan