The Death of a Political "I:" the Subcomandante is Dead, Long Live the Subcomandante!

Diana Taylor

In a final coup d’theater during a memorial for a fallen colleague known as Galeano, Subcomandante Marcos declared himself dead. Shortly after two in the morning on 24 May 2014, he addressed the thousand or so people who accompanied him, including journalists from the alternative, noncommercial media. The anticipation of those waiting in the rain must have been palpable—Marcos had not appeared in public since 2009. Rumor had it he was dying. Marcos had absented himself as the face of the Zapatista movement long before he publicly disappeared himself that pre-dawn morning in May. Only a few emails authenticated by his signature savvy good humor and multiple post-scripts had sustained belief in his continued existence. In his address that early morning, “Between Light and Shadow,” he asked for patience, “because these will be the final words that I speak in public before I cease to exist” ("Between Light and Shadow"). He went on to recount how “Marcos” as charismatic leader came into existence in the first place, right after the 1994 rebellion. Although the uprising had taken Mexico and the world by surprise, the Zapatista leadership recognized that they still “couldn’t see us.” Indigenous peoples remained invisible to their oppressors, who saw only the mestizo in the ski mask. The media anointed Marcos the spokesperson for the Zapatistas, although that position had in fact been assigned to an indigenous Zapatista killed in the uprising. In an act of surrogation, “Marcos” came into being, taking the place of the dead colleague.[1] “And so,” he says in his final address as Marcos, "began a complex maneuver of distraction, a terrible and marvelous magic trick, a malicious move from the indigenous heart that we are, with indigenous wisdom challenging one of the bastions of modernity: the media" ("Between Light and Shadow").

“These will be the final words that I speak in public before I cease to exist...”

There are so many ways to think about this auto-coup, this declaration of an "I" (Marcos) who ceases to exist spoken by an "I" who is not Marcos.

Marcos, not Marcos, not not Marcos.[2] "Marcos," the invention, will now live in quotation marks.

This was not Marcos’ first act of surrogation. Rafael Guillen Vicente, (supposedly Marcos’s "real" name, although he disputes that, too, in this last speech) had joined the military arm of the Zapatistas more than ten years before the 1994 uprising. Back then, he called himself “Zacarias” and took the name of Marcos in honor of his friend Mario Marcos, a fellow Zapatista who had been killed in 1983 (Oikonomakis 2014). As Leonidas Oikonomakis reminds us,

adopting the nom de guerre of a fallen comrade is nothing new in Mexico’s revolutionary history, or in the history of the EZLN [Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, or Zapatista Army of National Liberation] itself. It’s actually a tradition, for the fallen comrade not to be forgotten but rather to “live on” through the adopted nom de guerre. Let’s not forget, for example, that Pancho Villa—to talk about the Mexican Revolution of 1910—was born Doroteo Arango. Pancho Villa was a fallen comrade of his, killed by the village guards, and Doroteo adopted his friend’s name for him to continue to live in death. (2014)

"Marcos," like the mask, was a "colorful ruse," a "hologram" born of the uprising that reflected the aspirations of those who longed to challenge the regimes of domination. But in opposition to the negative spin Marcos puts on the hoax in 2014, "masquerading" (if we can even call it that) was enormously productive and generative. "Marcos" signaled the powerful potential of indeterminacy—the capacity for invention and reinvention, the willing into being, into the light of a power that was always there, potent, but in the shadows. "El México profundo," as Bonafil calls it (1987). "Marcos"was always collective—never a singular "I." As Paul Preciado writes, Subcomandante Marcos is like a drag-king:

the intentional fiction of masculinity (the hero and the voice of rebellion) based on performatic techniques. A revolutionary symbol without face or ego, made up of words and collective dreams. [...] [His queer/ trans act] de-privatizes the face, the name, in order to transform the body of the multitude into the collective agent of revolution. (2014)

Now, in 2014, “Marcos” had become redundant, unnecessary, a "distraction." "This figure," as el Sup (Marcos is sometimes informally referred to as “el Sup”) put it, "was created and now its creators, the Zapatistas, are destroying it” ("Between Light and Shadow"). While pronouncing “Marcos” dead, the Sup allows himself to be surrogated, publicly acknowledging and acquiescing to "chief and spokesperson of the EZLN, Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés."

Why was "Marcos" no longer necessary? The man formerly known as Marcos gave a few indications. Various shifts had tilted the center of the movement in a different direction. Some were generational: “The little girls and boys who used to crowd around to hear his stories will not miss him; they are grown up now” ("Between Light and Shadow"). The younger generation, born into Zapatismo, was taking the lead. Moreover, the movement was re-indigenizing itself—shifting decision making to its indigenous leaders and developing other, more horizontal, leadership strategies (“rule by obeying”). Other shifts reflected the growing involvement of civil (over military) leadership as the Junta del Buen Gobierno (Council of Good Government) took root as a governing structure in the five caracoles, or autonomous Zapatista communities. As recently as 2013-14, the escuelita, or Zapatista "little school," had accepted thousands of participants from throughout the world to learn the ways of collective struggle. The support from civil society bolstered their fight for life and dignity. In short, the heroic figure of a mestizo man in military attire had begun to undercut the ethos of a broad, collective, life-affirming movement that was far more powerful and impressive than any one leader. Charismatic leaders, the younger generations throughout the world are learning, make a movement vulnerable. The loss of the leader through death or co-optation could entail the loss of recognition or direction of the movement itself. The end of “Marcos” foreshadowed another end as well—the end of the EZLN as an armed force: “this is the way that we [as an army] could ultimately disappear” ("Between Light and Shadow"). The style of political performance was undergoing change, not just in Mexico but throughout the world—from what “Marcos” calls “revolutionary vanguardism” that includes the recognizable leader (Che, Marcos) to the collective, be it the indigenous communities or the 99%.

But how could the Zapatistas kill Marcos? For years they leaked rumors of his terminal illness to their confidants in the press, knowing they were using the press as a weapon much as the press had used them. “Time and time again we planned this, and time and time again we waited for the right moment” ("Between Light and Shadow")

The assassination of compañero “Galeano” on 2 May 2014 provided the occasion for the death of Marcos. Mexican paramilitary forces entered La Realidad, one of the Zapatista caracoles, and murdered Jose Luis Solis López, a teacher at the escuelita, and injured 15 others. They destroyed the school, the clinic, and other structures. Solis López had named himself “Galeano” after Eduardo Galeano, author of the 1971 text The Open Veins of Latin America (Preciado 2014). Open Veins, a major contribution to anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist thought in Latin America, situated Eduardo Galeano as an icon of the left. But an article published the same day of the compañero Galeano’s murder reported Eduardo Galeano’s statement at an event celebrating the 43rd anniversary of the book: “I wouldn’t be capable of reading the book again” (Rohter 2014). He did not have the “necessary education” in economics and politics at the time he composed it, he said, and “that traditional leftist-style prose is awful:” another act of self-disappearance among the many in this performance (Iaconenangelo 2014).

In the last act of surrogation carried out in the early morning hours of 24 May, Subcomandante Marcos bids farewell to his audience. “And in the end, those who have understood will know that he who never was here does not leave; that he who never lived does not die.” After his speech and post-scripts ("P.S. 1: Game over? P.S. 2: Check mate? P.S: 3. Touché?[...] P.S. 6: Great, now that the colorful ruse has ended, I can walk around here naked, right? P.S. 7: Hey, it’s really dark here." Marcos, like Goethe, needs a little more light), he leaves the stage. There is a shocked silence and then prolonged applause. Subcomandante Moisés announces that another compañero will address the crowd. The Sup comes back: “My name is Galeano, Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano... Ah, that’s why they told me that when I was reborn, it would be as a collective.[3]

There is something wonderfully theatrical about this switch, but also something profound. It draws from an ancient Mayan repertoire. In Popul Vuh, one of the founding recountings of the Maya, the Hero Twins, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, are killed and dismembered after losing a ball game in the underworld only to be reborn. Challenged again to a ball game in the underworld, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué accept and triumph. But the death and rebirth also speaks to the history of perseverance, loss, and renewal in the face of the over five hundred years of colonization, not to mention the current political crisis. "Marcos" dies so that "Galeano" might live, but the speech makes it clear that this is not just about the murdered teacher. The man who was Marcos recites a list of names of the dead, just a few of the many thousands of dead from Mexico’s civil strife, internal battles, and violence against migrants. Dead. More dead. Over 80,000 dead and 30,000 disappeared since 2006. And yet, the non-violent resistance and active struggle for justice and dignity continue. Many die, and many others take up their cause and continue the struggle. Life needs to affirm itself in the face of this humanitarian crisis. Instead of Galeano, who did “not deserve to die, not like this,” they offer up “he who does not exist and has never existed, except in the fleeting interest of the paid media” ("Between Light and Shadow").

I find Marcos’ act brilliant, but something bothers me about his speech, for all its humor and wisdom. There’s the disparaging tone of Marcos’ treatment of “Marcos:” “Those who loved and hated Sup Marcos now know that they have loved and hated a hologram. Their love and hate have been useless, sterile, hollow, empty.” No. Not useless. Loving (and perhaps hating) Marcos has been an important part of the history of the left in Latin America, just as admiring (or critiquing) Eduardo Galeano has been. “Marcos” reactivated the trickster’s potential of enormous trans-possibility: trans-race, trans-gender, trans-personal, trans-national, trans-historical. Narrative, like Open Veins, outlives its author. People can decide for themselves if they agree with the Eduardo Galeano of the 1970s or of the 2010s. Performance works differently, through reiterated repertoires and memes. The figure of “Marcos” pulls, as I suggest, from a repertoire of earlier acts of surrogation—from the Popul Vuh to Pancho Villa and beyond. But “Marcos” as a meme has the force of an idea—resistance, rebellion, trans-boundaries. It doesn’t matter if he exists (Santa), or if he’s alive (Che), or if he (dis)identifies with his image. Memes catch on; they go viral (online and off); they appear in various parts of the world in differing contexts. Memes are not true or false. They’re contagious or they’re nothing. Everyone knew that “Marcos” was a role, just as every political figure is, but the memetic (as opposed to mimetic) force of his performance was that he was able to personify the thoughts and priorities of a movement far older and greater than he was. Now, in this last speech, he again brings us face to face with the brutality of contemporary Mexican politics through his words. We hear the names of the dead as he pronounces them. Time for “Marcos” to exit, to morph into something else again, maybe. But it is unnecessary, I believe, to disparage what “Marcos” accomplished. Sup "Galeano" may do differently, but he can never do better.

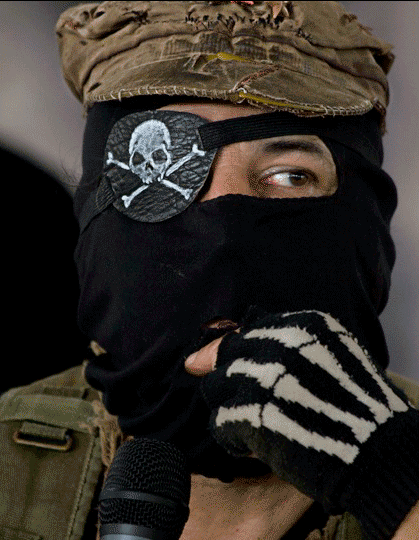

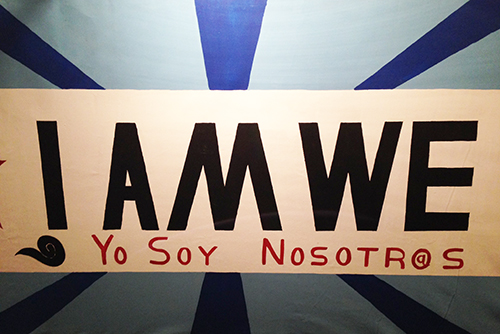

Sup Galeano reappears with a skull and crossbones patch over his right eye and a glove with skeletal fingers painted on them. This image of death also activates a rich repertoire. Maybe the act of self-annihilation will draw fresh attention to the Zapatistas via the media that Marcos disparages. But that media barely took up the news of Marcos’ "death." Political reporter Chris Hedges calls on us to “become Zapatistas.” (2014) But what would that mean? Marcos already answered that: “It is one thing to say, ‘We Are All Marcos’ or ‘We Are Not All Marcos,’ depending on the situation, and quite another to endure persecution with all of the machinery of war.” How can "we" who attend this performance online or in the flesh be the interlocutors that the Zapatistas need us to be? The ones who can understand the stakes of ongoing struggles and align ourselves with the Zapatistas’ call for freedom and justice? What’s to be done, by "him," by them, and by us? “Maybe later—days, weeks, months, years or decades later—what we are about to say will be understood” ("Between Light and Shadow").

“Marcos'” final speech is a puzzle: “he who has never lived does not die” undoes “he who does not exist and never existed.” Dead, not dead, not not dead. But how, he asks, “do you kill what was never alive?” How, in other words, can you kill the Marcos meme? You can’t. The man who was Marcos may die, but “Marcos” will live as long as he fulfills a symbolic function. Much like Che, he may come to epitomize the idea of the heroic figure of anti-imperialist armed struggle from the periphery of the mountains and the jungles that has now given way to collective protest on the streets of major cities around the world. The struggles may have shifted, but they have not died. You can kill individuals, Marcos recognizes in his final speech, but you can’t kill an idea. How did he ever imagine he could kill “Marcos”? The Subcomandante Marcos is dead! Long live the Subcomandante!

NOTES

>[1]“The EZLN did not intend the world to see a mestizo, a Mexican of mixed blood, at the head of an indigenous army. For that, an indigenous Zapatista had been selected to be spokesperson. Unfortunately, he died shortly after the attack and Marcos took over the role of spokesperson, with huge success. Seeing the fascination of the Mexican and international media with the mysterious persona of Marcos, the EZLN decided to take advantage and “use” this allure in order to attract more and more attention and stay in the spotlight” (Oikonomakis 2014).

[2]I am indebted to Richard Schechner for the not/not not frame (Schechner 1985).

[3]To hear the speech, visit http://komanilel.org/AUDIO/EZLN/entreLaLuzyLaSombra.mp3.

“Between Light and Shadow.” 2014. Enlace Zapatista. Accessed 27 May 2014.

http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2014/05/27/between-light-and-shadow/.

Bonafil-Batalla, Guillermo. 1987. México Profundo: Una civilización negada. Ciudad de México: CIESAS.

Hedges, Chris. 2014. “We All Must Become Zapatistas.” Truthdig, 1 June. Accessed 8 June 2014.

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/we_all_must_become_zapatistas_20140601.

Iaconangelo, David. 2014. “Eduardo Galeano Will No Longer Read His ‘Awful’ Book ‘The Open-Veins of Latin America’ At Public Appearances.” Latin Times, 2 May. Accessed 2 May 2014.

http://www.latintimes.com/eduardo-galeano-will-no-longer-read-his-awful-book-open-veins-latin-america-public-170492/.

Oikonomakis, Leonidas. 2014. “Farewell Marcos, long live Subcomandante Galeano!” Roarmag, 26 May. Accessed 26 May 2014.

http://roarmag.org/2014/05/subcomandante-marcos-steps-down-galeano/.

Preciado, Paul B. 2014. “Marcos for ever.”Libération, 6 June. Accessed 15 June 2014.

http://www.liberation.fr/chroniques/2014/06/06/marcos-for-ever_1035394.

Rohter, Larry. 2014. “Author Changes His Mind on ‘70s Manifesto” The New York Times, 23 May. Accessed 8 June 2014.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/24/books/eduardo-galeano-disavows-his-book-the-open-veins.html.

Bonafil-Batalla, Guillermo. 1987. México Profundo: Una civilización negada. Ciudad de México: CIESAS.

Hedges, Chris. 2014. “We All Must Become Zapatistas.” Truthdig, 1 June. Accessed 8 June 2014.

Iaconangelo, David. 2014. “Eduardo Galeano Will No Longer Read His ‘Awful’ Book ‘The Open-Veins of Latin America’ At Public Appearances.” Latin Times, 2 May. Accessed 2 May 2014.

http://www.latintimes.com/eduardo-galeano-will-no-longer-read-his-awful-book-open-veins-latin-america-public-170492/.

Oikonomakis, Leonidas. 2014. “Farewell Marcos, long live Subcomandante Galeano!” Roarmag, 26 May. Accessed 26 May 2014.

http://roarmag.org/2014/05/subcomandante-marcos-steps-down-galeano/.

Preciado, Paul B. 2014. “Marcos for ever.”Libération, 6 June. Accessed 15 June 2014.

http://www.liberation.fr/chroniques/2014/06/06/marcos-for-ever_1035394.

Rohter, Larry. 2014. “Author Changes His Mind on ‘70s Manifesto” The New York Times, 23 May. Accessed 8 June 2014.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/24/books/eduardo-galeano-disavows-his-book-the-open-veins.html.

Schechner, Richard. 1985. Between Theatre and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

| Previous page on path | Essays, page 13 of 17 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "The Death of a Political 'I:' the Subcomandante is Dead, Long Live the Subcomandante!"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...