The Murals at Oventik: A Photo Essay

by Lorie Novak

Back

Entering Oventik the first time in 2009 and seeing the road going down the hill, lined with painted houses, is a visually overwhelming experience. The first building as we pass through the gates is the Sociedad Cooperative Arte de Mujers por La Dignidad (Arts Cooperative of the Women of Dignity) with murals on either side of the door. On the right there is a mural with a man and women holding guns with a child in between them holding the Mexican Flag. The woman is surrounded by calla lilies like those painted by the great Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. They form an aura around her much like the one around the Virgen of Guadalupe, which we see depicted on the walls of the medical center in the center of the caracol. To left of the door a group of women stand together – a few of the women gaze at the viewer, but most look to the right and seem to be on the move. Some have guns; one has a guitar. The woman on the far left looks like the artist Frida Kahlo. A jaguar and a young boy holding a gun complete the group. Between my trips in 2010 and 2013, a masked snail has been added to the group. I don’t notice this until my return to New York. I am taken aback by the originality of the murals but surprised by the art historical references to Diego and Frida. Later on I see the Zapatista version of Matisse’s famous dancers.

The next building has Oficina de Mujeres por la Dignidad painted in huge letters on it. A masked woman with a baby on her back is painted to the right of the door. I take a photograph to put on my office door at NYU. When I return in 2013, she has been repainted—her left arm is raised in the air holding a flower and a gun is slung over her right shoulder. The baby is still on her back.

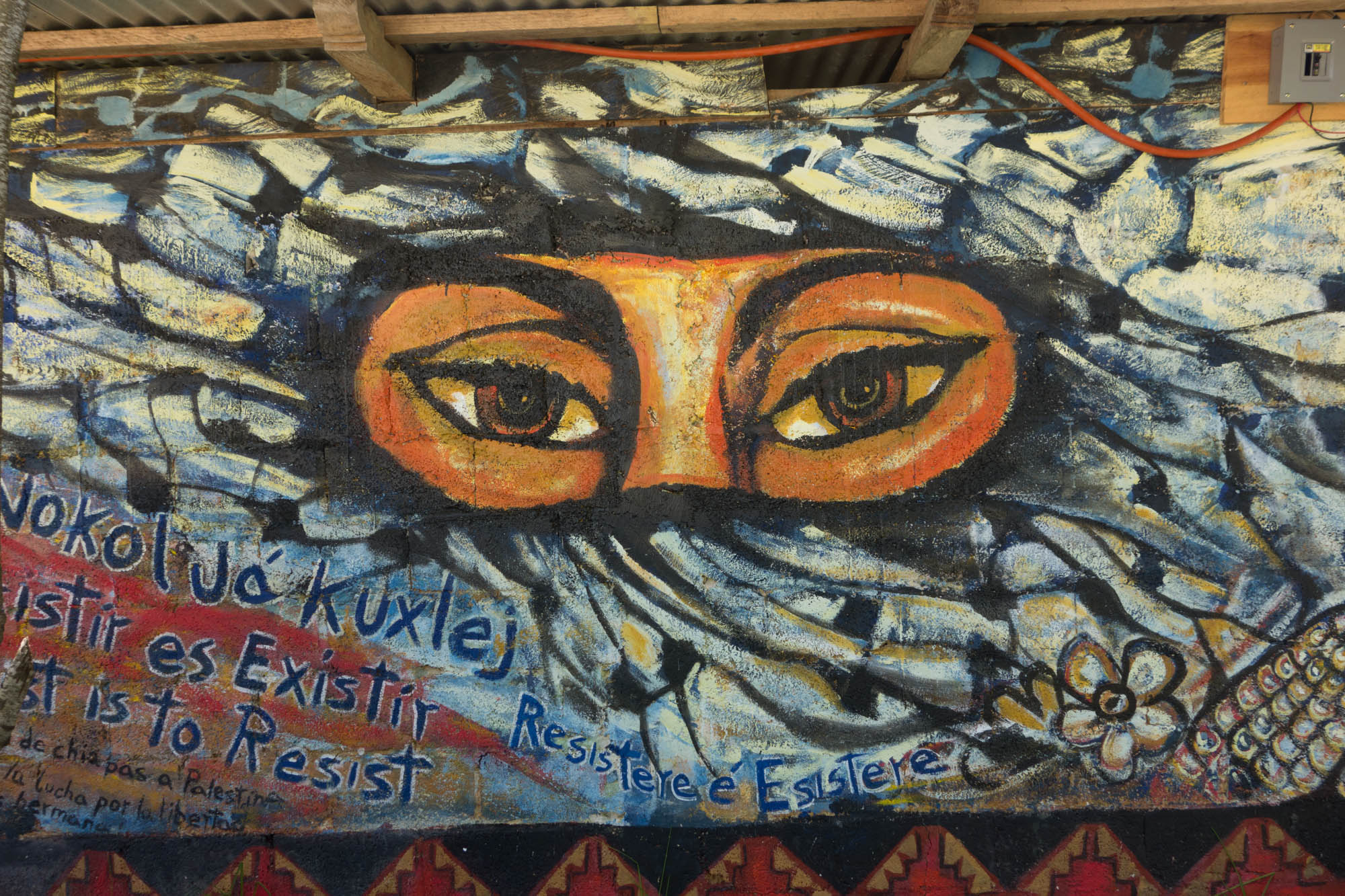

Walking through Oventik, the murals are my guides. It is hard to resist frantically photographing every one. I wander away from the group so I can slow down and take them in. It is the images of women I notice most. They are looking at me, standing guard with guns, reading, weaving, dancing, singing, flying, and holding up the sky. It wasn’t until my third trip that I became cognizant that the murals were in Spanish with only a minority also written in Tsotzal or Tsotzil, the first languages of the Zaptistas.

Seeing my favorite murals again on my second and third trips was like seeing old friends. I visited them all, re-photographing some. I could tell they are well cared for—my favorite one of the women with the red bandana clearly had been repainted and restored – she was glowing in 2013. Some seemed to have been painted over, and new ones added. It wasn't until I got home and looked through my photographs from previous years that I saw how many had changed over the years. When getting face-lifts, they are also transformed. [see Luis Vargas-Santiago essay for a thorough analysis of the murals]. This pastiche effect is ideological, aesthetic, and political as murals are constantly updated to respond to current conditions (not least of all the weather).

Even viewing the photographs on my computer, I can still hear the walls speak to me about hope, patience, love of the land, love of books and education, the importance of community, safe sex, and that corn is life, freedom lives, and how the struggle continues.

Discussion of "The Murals at Oventik: A Photo Essay"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...