Scalar's 'additional metadata' features have been disabled on this install. Learn more.

Featured Books

Writing With Substance

Vimala C. Pasupathi

Entanglements

Diana Leong, Mark C. Marino, Jessica Pressman

Pathfinders

Dene Grigar, Stuart Moulthrop

FemTechNet Critical Race & Ethnic Studies Pedagogy Workbook

Anne Cong-Huyen, Christofer Rodelo, Erica Maria Cheung, alex cruse, Regina Yung Lee, Katie Huang, George Hoagland, Dana Simmons, Sharon Irish, Amanda Phillips, Veronica Paredes, Genevieve Carpio

Scalar 2 User's Guide

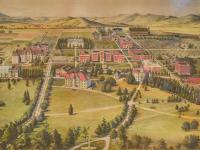

A Photographic History of Oregon State University

Larry Landis with OSU Digital Publishing

Complex TV

Jason Mittell

Growing Apart

Colin Gordon

Performing Archive

Jacqueline Wernimont, David J. Kim, Stephan Schonberg, Amy Borsuk, Beatrice Schuster, Heather Blackmore, Ulia Gosart (Popova)

Sound and Documentary in Cardiff and Miller's Pandemonium

Cecilia Wichmann

Unghosting Apparitional (Lesbian) History

Michelle Moravec