Introduction, Page 9

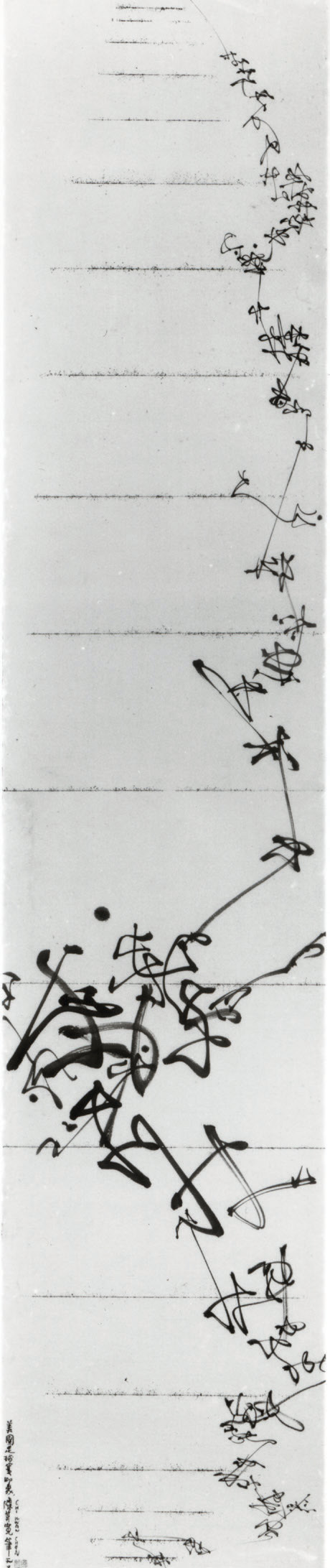

Chen Chi-kwan moved to the United States in the late 1940s to study architecture and soon found himself in Boston working for Walter Gropius (1883–1969), and later in New York City working for I. M. Pei (b. 1917). During this period, “C. K. Chen” lived alone in the downtown Manhattan YMCA, where he created and exhibited a series of highly original ink paintings that were exquisitely and sharply drawn, bristling with the simple vitality of artists like Qi Baishi. Among his most abstract and famous paintings are a series entitled Ball Game (Fig. 7), which recalls the mapping of a football down the field. Although Chen moved to Taiwan in the 1960s to work as an architect, he maintained an important American presence until his death in 2007.

Chen Chi-kwan moved to the United States in the late 1940s to study architecture and soon found himself in Boston working for Walter Gropius (1883–1969), and later in New York City working for I. M. Pei (b. 1917). During this period, “C. K. Chen” lived alone in the downtown Manhattan YMCA, where he created and exhibited a series of highly original ink paintings that were exquisitely and sharply drawn, bristling with the simple vitality of artists like Qi Baishi. Among his most abstract and famous paintings are a series entitled Ball Game (Fig. 7), which recalls the mapping of a football down the field. Although Chen moved to Taiwan in the 1960s to work as an architect, he maintained an important American presence until his death in 2007.Beijing-trained Tseng Yuho (b. 1925) married art historian Gustav Ecke and moved with him to Honolulu in 1949, where they both taught art history at the University of Hawaii for decades. In America, Tseng developed a unique and innovative collage technique she called dsui hua (assembled painting), which incorporated metallic paper and sometimes seaweed to create works that seemed to glow with the spirit of Chinese painting even though they were in fact devoid of actual ink.

C. C. Wang (1907–2003) moved to New York in 1949 and became an esteemed teacher and connoisseur of Chinese painting. In the 1950s, his garden apartment on Riverside Drive in Manhattan became the original venue for Mi Chou, the first Asian American art gallery in America. There, artists like Chen Chi-kwan first exhibited their work. Beginning in the late 1960s, Wang found his voice as a painter, using crinkled paper blotted with ink to create abstract patterns from which he would develop monumental landscapes. Watercolor artists in New York like Frederick Wong had earlier used crinkled paper for dramatic effect in the late 1950s in works that were exhibited at Mi Chou, but C. C. Wang applied the technique to painting with ink. Late in his life, C. C. Wang developed another powerful body of work that incorporated an abstract web of arcing, intersecting linear elements that appear to reference archaic Chinese characters (Fig. 28).

Several scholars are also important to name in this history. Wang Fangyu (1913–1997) moved to New York in 1945 and earned a master’s degree from Columbia in 1946. He taught Chinese language literature at Yale University from 1945 to 1965 before moving to Seton Hall University in New Jersey. At Seton Hall, he helped support Chinese cultural programming and exhibited his innovative works of calligraphy along with scholar/artists including Kai-yu Hsu, noting, “I belong to a very small group of Chinese artists, painters, and calligraphers of the second half of the twentieth century who have succeeded in revitalizing an art form without turning our backs on tradition.”4 Kai-yu Hsu was similarly a scholar of Chinese language and literature and was very influential at San Francisco State University after his 1959 hire, and he grew passionate about painting in his later career. Charles Chi-jung Chu (1918–2008) arrived in the United States in 1945 to study first at U. C. Berkeley and later at Harvard, then teaching Chinese language at Yale for fifteen years and then at nearby Connecticut College, where he directed the Chinese program. There, he was a lifelong advocate of Chinese culture and established a study collection.

Chen Chi-kwan. Ball Game

(c. 1952). Ink on paper, approx. 47.25 x 9.75 in. Courtesy of

the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, New York.

| Previous page on path | Introduction Path, page 9 of 10 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Introduction, Page 9"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...