Introduction

This Module:

Mi Chou Gallery Catalog at Freeman's Auctioneers and Appraisers, September 14, 2013Remapping Ink Painting: A Contemporary Evolution, Public Conversation with Wucius Wong, Lam Tung-pang, Mayching Kao and Pauline Yao, moderated by Mark Dean Johnson, July 13, 2013

Conversation with Paul Hao, 97 year old artist, at San Francisco State University, February 2013 (forthcoming)

Interview with Lucy Arai, 57 year old artist, at San Francisco State University, January 2013

Contributors

VAAAMP

Curated Paths

Artists

Tags

Art Educators

Documenting the History of Ink Painting in America

Toshio Aoki. Shõki and Demons (1870s). Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 49.055 x 20.12 in. Clark Family Collection, on long-term loan to the Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture.

About ten years ago, the preeminent twentieth-century Chinese art historian Michael Sullivan made an offhand comment that stunned me. We were discussing the work of Chinese artists he had known when Professor Sullivan said, matter-of-factly, “Many of the most important Chinese painters during the second half of the twentieth century lived in the United States.”

This exhibition and catalog together examine the work of some of the Chinese artists to which Sullivan was referring, featuring them alongside their Japanese and non-Asian counterparts who were concurrently working in the medium of ink. Our principal goal is to reclaim this internationally important but mostly invisible history of Asian American ink painting.

This project also makes comment on the circumstances that may have contributed to the unexpected flowering of the genre in American art. It postulates the value of using a Sino-American perspective to explore the contributions of important but largely “under-recognized” twentieth-century American artists who as a group forged an aesthetic reflecting Asian/American international influences and who in fact helped set the stage for a twenty-first-century generation of artists who have captured the attention of the world.

Before considering these artists and their work, it is important to reflect on the historical circumstances that contributed to the cultural period out of which they emerged. Within the canon of American art history, it is widely recognized that many European intellectuals and artists relocated to the United States as a direct result of the political turmoil beginning in the 1930s in Europe that eventually led to World War II. Among these figures are Josef Albers, Willem de Kooning, and Hans Hofmann,who, together with their contemporaries, are today widely recognized as energizing what would come to be known as the New York School. But wars, revolutions, and political instability were similarly disruptive in Asia during this period, and the unrest precipitated the parallel emigra- tion of many Asia-born artists. Sometimes these artists moved to New York, but often they dispersed to geographical regions throughout the Americas, with a significant number concentrating in the state of California. These artists have been much less recognized than their European peers.

The reasons for this relative invisibility are multiple. American art, like American history, is traditionally mapped from its beginning in European colonialism. Our English language is the strongest marker of this legacy. Connected to this is the centrality afforded to artistic developments centered in New York. But with the ensuing waves of postcolonial immigration, and especially from the current project’s perspective from the American West Coast, America’s art and cultural history looks altogether different. Among the starkest contrasts is the wealth of Asian American culture that is integral in this region.

Of course, many ideas and practices drawn from Asia are acknowledged as common- place in the United States, including the impact of religious philosophies and literature, martial arts and alternative medicine, and cuisines. But visual art is inherently a more esoteric subject. Most people are aware that the great painting traditions of East Asia are often grounded in painting with ink on paper or silk, with a bamboo and soft-hair brush. Especially in the West, however, little is known of ink painting’s iconography, underlying philosophy and history, relationship to calligraphy, and aesthetics.

Because vocabulary including sumi-e (ink painting) and guohua (Chinese painting) have rich nationalist associations with the countries of Japan and China, respectively, this project instead intentionally uses the neutral English language terminology of “ink painting.” By doing so, we attempt to build a transnational dialog that reflects transcultural exchanges and expressions in a multiethnic American context. However, while we do not want to foreground any one of these national traditions to the exclusion of others, it is also important to study and reference the specificity of these great individual traditions from Asia. Only in that way might we develop a more global sophistication that does not chauvinistically privilege our ignorance and reduce multifaceted complexity to meaningless generalizations. A polycentric approach is important as many of the artists whose work is explored here relied on the iconographic and philosophical foundations of Asian ink painting even as they expanded into new stylistic territory inspired by their new geographies.

It is also important to note at the outset that by the early twentieth century there was not only widespread awareness and training in oil painting in most Asian countries but broad interest in Asian art in the West, so any discussion of an East/West cultural polarity needs to be carefully dissected to expose its nuance. In fact, such wide-ranging international exchange between the high cultures of Europe and Asia can be traced to the Renaissance.1 Japan incorporated the Western art education of perspective and modeling as early as the 1870s. Several influential teachers in China, including Xu Beihong (1895–1953) and Lin Fengmian (1900–1991) brought their direct experience of School of Paris color and spontaneity to their classrooms by the 1920s. Perhaps because of this influx of new attitudes and approaches, early-twentieth-century art in Asia is incredibly dynamic. The lush Meiji- and Taisho-period painting in Japan and the individual achievement of artists like Taikan Yokoyama (1868–1958), who spent time in Boston at the turn of the twentieth century and studied at Boston Museum of Fine Arts curator Okakura Tenshin’s (1862– 1913) Tokyo school, are highly appealing. Powerfully inventive works by artists like Qi Bai- shi (1864–1957) and Pan Tianshou (1897–1971) in China effectively reawakened the giant ink-painting legacy that had become staid and predictable by the late Qing Dynasty. Pan Tianshou’s brilliant, inventive, and varied late-oeuvre brushwork, created in the 1950s and 1960s, stands as the starkest reminder that great ink painters continued to work in China after the mid-century.2 But horrifically, it is important to remember that Pan was specifically targeted principally because of his brilliant aesthetics; his intellectual and physical persecution led to his early death during the Cultural Revolution. At the same time, we will see that the initial blossoming of ink expressions on American soil have continued to flower.

In this introduction, many artists will be only briefly mentioned and positioned within their historical context; more substantive discussion of their works appears in the individual captions accompanying reproductions in the catalog section of this publication.

Our American research project begins with the dramatic appearance in California of a distinctive style, influenced by Japanese Nihonga, by artists who had been trained in Japan. Nihonga refers to the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artistic movement characterized by a return to Japanese-style painting, including ink on paper and silk. The majority of early Japanese artists in the United States worked in oil on canvas, reflecting training still predominant in Japan as well as in America. During this time, artists like Toshio Aoki and Chiura Obata, from different generations (Obata was born more than thirty years after Aoki) and representing different artistic approaches, became among the most successful artists of their period working in a clearly non-Western style. Aoki signed most of his California-period paintings with an inscription in kanji that translates as “Great Japan.” But Japan’s political environment at that time was in fact categorized by a repressive agenda in which democratic political thought was not much tolerated.

Aoki, born in 1854 in Yokohama, relocated to California in 1880 when he was hired as a professional artist to create Japanese decorative objects for sale in a San Francisco department store. He brought with him a personal aesthetic of darkness and mystery that has been compared to the mood of his Japanese printmaking contemporary Tsukioka Yoshi- toshi.3 In one early painting dating roughly from the period of his relocation to the United States (and in the collection of the Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture in Hanford, California Fig. 1), Aoki painted an unusually dark vision of Zhong Kui, the Chinese King of the Ghosts. In that painting, Zhong Kui is shown unconventionally reclining in an underground lair overrun with scores of grotesque demons crawling on and around him. The scroll is itself mounted on unusual batik fabric. This engaging image and uniquely mounted scroll-format presentation suggests why Aoki became something of a sensation in his day. While he occasionally experimented with conventional modeling and the subjects of period oil painting in California, Aoki was most widely recognized for his newspaper and book illustrations, his wall decorations (sometimes on painted leather) for the interiors of lavish homes in Pasadena, and his ink and watercolor paintings of figures from Chinese and Japanese mythology, all in a distinctive style related to what is sometimes called Japonisme. Although we are only at the beginning of understanding Aoki’s oeuvre (only a relatively small percentage of his work has been recovered/documented to date, after a century of art historical disinterest), his artistic success during his lifetime put him in contact with the wealthiest elite of American society, and he was therefore well represented in period press. He exhibited widely across America during his lifetime, including at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, where influential Zen scholar D. T. Suzuki and Indian Buddhist intellectual Anagarika Dharma- pala participated as speakers.

Obata arrived in the United States more than twenty years later than Aoki, in 1903. In contrast to Aoki’s nostalgia for “Great Japan,” Obata professed a transcendental and environmentalist passion for “Great Nature.” Like Taikan before him, his work reflected his classical training in Tokyo with leading practitioners of Nihonga, including Gaho Hashimoto (1835–1908). Obata sometimes referenced Japanese classical art—for example, his 1927 sketchbook renderings of trees (Fig. 2) clearly evoke Tohaku Hasegawa’s revered Momoyama-period Pine Trees, from more than three centuries earlier (Fig. 3)—yet unlike Aoki, Obata’s paintings are more generally based in direct observation. His landscapes reference specific California locations, including views of Yosemite, the High Sierra, and Point Lobos on the Monterey Peninsula, and his synthesis of American landscape traditions with Japanese decorative aesthetics gives his work an accessible and appealing quality that has repeatedly reasserted itself since his initial renown during the 1920s.

Art historical recognition of artists like Aoki and Obata has been slow in coming. The reasons for this bear our consideration. For starters, most Asian-language calligraphy inscriptions are completely unintelligible. Further, Asian names are less familiar and as such are more forgettable. Even Americans with interest and training in the visual arts can usually name only a few Asian artists—generally contemporary figures like Takashi Murakami (b. 1962) and Ai Wei- wei (b. 1957), made famous by their pop cultural references and high-profile politics. American responses also equate excellence in visual art with modernist innovation and therefore harbor suspicions about art education in Asia, which is traditionally based in copying. American art education itself ignores most Asianist approaches to both iconography and philosophy, except in relation to Euro-American-centric ideas like postmodernism, an oversight that makes it more difficult to appreciate work based in that alternative achievement. But maybe more importantly, Japanese immigrant artists were ineligible for U.S. citizenship until 1952, nine years later than for immigrants from China. Today, we can embrace their achievements and recognize their complicated identities, which fell between the cracks of U.S. immigration laws. This early generation of artists also commonly suffered racist attacks, including being beaten and spat upon in public, even while they were celebrated for their refined artistry. This real inequity inherent in the American society of that period is important to keep in mind, as it renders the professional achievement of these individuals even more socially significant and noteworthy.

During the 1920s and 1930s, when experimentation with figuration was a hallmark of early American modernism and regionalism movements, a number of other artists of Asian ancestry developed innovative approaches to painting with ink. The most renowned of these was Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1893–1953), who was among the best-known American artists during the period between the First and Second World Wars, although his fame has faded considerably since his death. Although Kuniyoshi was primarily an oil painter, he also created many images using ink on paper that are too richly modeled to be described simply as “drawings.” Kuniyoshi said he was interested in creating an “East-West” stylistic fusion, balancing working with ink and copious white space in compositions that also reflected his quirky rendering style inspired by American folk art. His sensuous 1924 drawing Leaves in a Vase (Fig. 4), in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, is an example of his sophisticated synthesis. Noboru Foujioka was an artist closely associated with Kuniyoshi’s circle who lived in both New York and California during this period and was also primarily an oil painter. He created ink sketches that give his 1920s subjects, like the woman in one untitled work (Fig. 5), the immediacy of Zen painting’s fresh and uninhibited brushwork.

Some artists during these decades often looked to explore the legacy of ink painting as an Asian cultural signifier. Japanese American printmakers of the 1920s, like woodblock artist Teikichi Hikoyama (1884–1957) and etcher Kazuo Matsubara (1885–unknown; see Fig. 6), and scores of Japanese American modernist photographers borrowed tropes from Japanese classical art in their contemporary work. Long before the development of art derived from identity-based cultural politics, many Asian American artists were interested in expressing their engagement with the high culture of Asia, even if they were educated in— and sometimes even born in—the United States. Artists including Tyrus Wong (b. 1910), who was educated at the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, and Wing Kwong Tse (1902–1993), who was educated at the University of Southern California but worked in San Francisco, developed innovative ink paintings during the 1930s. Both Wong and Tse were born in China but moved to the United States as children. Similarly, some of the leading figures of the regionalist American watercolor movement of this period were also Chinese American, including Oakland-born Dong Kingman (1911–2000), who was celebrated on the West Coast in the 1930s, and Chen Chi (1912–2005), beginning in the 1940s in New York. Their art sometimes reflects the formats of scroll painting and compositional approaches learned from Chinese painting even though their use of watercolor pigments sets their work apart. The work of both was widely emulated.

Early proponents of a specifically Chinese-style ink painting in California included Yang Ling-fu, who first rose to prominence in China during the 1920s, becoming the first woman in China to be director of an art college. But because that school was located in Manchuria and in the path of the Japanese invading armies, she fled, relocating first to Europe and then, in 1936, to the United States. Shu-chi Chang and Wang Chi-yuan both moved to the United States in 1941. Initially, both arrived in California, but Wang soon moved to New York. Shu-chi Chang enjoyed a high profile after presenting to Franklin Delano Roosevelt a mural-scale ink and watercolor painting he had brought with him from China. Titled Messengers of Peace, the work included an inscription by Chiang Kai-shek. This painting also demonstrates Shu-chi Chang’s innovative blended brush technique, which incorporated thick white gouache with mineral pigment and ink in single strokes. Shu-chi Chang enjoyed a strong career of significant exhibitions in America’s most prestigious museums, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts during the years of World War II. He later had a successful business in art publishing. Meanwhile, Wang Chi-yuan was active in New York, where his work was collected and exhibited in homes as a proud marker of Chinese heritage.

All three of these artists had pursued an art education incorporating Western techniques as well as ink painting while still in China. Some aspects of their work reflect their efforts to create hybrid synthesis, sometimes including the depiction of specific American locations in their paintings. For Wang, this sometimes took the form of Hudson River scenes traversed by modern bridges; Chang occasionally painted scenes associated with Yosemite or the coast of Carmel-by-the-Sea. Nonetheless, these artists were principally recognized as ambassadors of Chinese art in the West, and as a result, their work functioned as a signifier of classical China, and their stylistic innovations were appreciated as more subtle than spectacular.

Within a decade, another dynamic generation of artists had arrived from Asia, also displaced by war and revolutions, and drawn to the United States by the relative peace and range of opportunities available during the same period. This cohort included Chinese artists such as Chen Chi-kwan, Tseng Yuho, and C. C. Wang, as well as the Japanese artist Saburo Hasegawa. Hasegawa had distinguished credentials as an early modernist: he had worked in Paris creating abstract oil paintings in the 1930s and was later a close friend of Isamu Noguchi. But after the war, he eschewed oil painting and returned to working in ink, albeit with an abstract orientation. Because of his return to ink media, Hasegawa’s work was criticized as conservative in Japan, but he continued to be very influential in the United States, both in New York and California. He was a friend to and influence on major American artists and writers including painter Franz Kline, poet Gary Snyder, and philosopher Alan Watts. Hasegawa was a proponent of tea ceremony and associated with the circle of Soto Zen Buddhist teachers like Hodo Tobase, who practiced and sometimes taught calligraphy in classes that were popular with diverse artists. Hasegawa created many innovative abstract works using unusual stamps and rubbings, and he became a prominent teacher in the mid-1950s at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland and at the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco. He died young, at the age of fifty in 1957.

Chen Chi-kwan moved to the United States in the late 1940s to study architecture and soon found himself in Boston working for Walter Gropius (1883–1969), and later in New York City working for I. M. Pei (b. 1917). During this period, “C. K. Chen” lived alone in the downtown Manhattan YMCA, where he created and exhibited a series of highly original ink paintings that were exquisitely and sharply drawn, bristling with the simple vitality of artists like Qi Baishi. Among his most abstract and famous paintings are a series entitled Ball Game (Fig. 7), which recalls the mapping of a football down the field. Although Chen moved to Taiwan in the 1960s to work as an architect, he maintained an important American presence until his death in 2007.

Chen Chi-kwan moved to the United States in the late 1940s to study architecture and soon found himself in Boston working for Walter Gropius (1883–1969), and later in New York City working for I. M. Pei (b. 1917). During this period, “C. K. Chen” lived alone in the downtown Manhattan YMCA, where he created and exhibited a series of highly original ink paintings that were exquisitely and sharply drawn, bristling with the simple vitality of artists like Qi Baishi. Among his most abstract and famous paintings are a series entitled Ball Game (Fig. 7), which recalls the mapping of a football down the field. Although Chen moved to Taiwan in the 1960s to work as an architect, he maintained an important American presence until his death in 2007.Beijing-trained Tseng Yuho (b. 1925) married art historian Gustav Ecke and moved with him to Honolulu in 1949, where they both taught art history at the University of Hawaii for decades. In America, Tseng developed a unique and innovative collage technique she called dsui hua (assembled painting), which incorporated metallic paper and sometimes seaweed to create works that seemed to glow with the spirit of Chinese painting even though they were in fact devoid of actual ink.

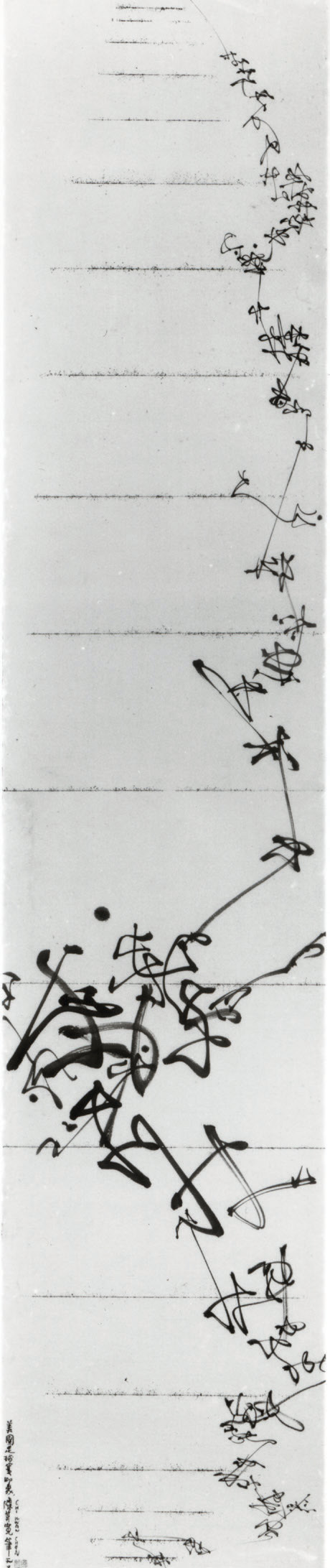

C. C. Wang (1907–2003) moved to New York in 1949 and became an esteemed teacher and connoisseur of Chinese painting. In the 1950s, his garden apartment on Riverside Drive in Manhattan became the original venue for Mi Chou, the first Asian American art gallery in America. There, artists like Chen Chi-kwan first exhibited their work. Beginning in the late 1960s, Wang found his voice as a painter, using crinkled paper blotted with ink to create abstract patterns from which he would develop monumental landscapes. Watercolor artists in New York like Frederick Wong had earlier used crinkled paper for dramatic effect in the late 1950s in works that were exhibited at Mi Chou, but C. C. Wang applied the technique to painting with ink. Late in his life, C. C. Wang developed another powerful body of work that incorporated an abstract web of arcing, intersecting linear elements that appear to reference archaic Chinese characters (Fig. 28).

Several scholars are also important to name in this history. Wang Fangyu (1913–1997) moved to New York in 1945 and earned a master’s degree from Columbia in 1946. He taught Chinese language literature at Yale University from 1945 to 1965 before moving to Seton Hall University in New Jersey. At Seton Hall, he helped support Chinese cultural programming and exhibited his innovative works of calligraphy along with scholar/artists including Kai-yu Hsu, noting, “I belong to a very small group of Chinese artists, painters, and calligraphers of the second half of the twentieth century who have succeeded in revitalizing an art form without turning our backs on tradition.”4 Kai-yu Hsu was similarly a scholar of Chinese language and literature and was very influential at San Francisco State University after his 1959 hire, and he grew passionate about painting in his later career. Charles Chi-jung Chu (1918–2008) arrived in the United States in 1945 to study first at U. C. Berkeley and later at Harvard, then teaching Chinese language at Yale for fifteen years and then at nearby Connecticut College, where he directed the Chinese program. There, he was a lifelong advocate of Chinese culture and established a study collection.

Chen Chi-kwan. Ball Game

(c. 1952). Ink on paper, approx. 47.25 x 9.75 in. Courtesy of

the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, New York.

View

| Previous page on path | The Moment For Ink, page 1 of 3 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Introduction"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...