Title Guarantee and Trust Building - The Spanish Period, 1769-1846

- In Ballin's Words

- Allegory and History

- Monumental Men

- Source/Citations

Ballin described his murals at the Title Guarantee and Trust Building in a pamphlet published in 1931:

“The second panel concerns itself with the rancho life manifesting itself in the Spanish and Mexican period – a period stretching indolently from 1769 to 1846. About midway therein life flowered at its best on the great ranches of Southern California.

“The second panel concerns itself with the rancho life manifesting itself in the Spanish and Mexican period – a period stretching indolently from 1769 to 1846. About midway therein life flowered at its best on the great ranches of Southern California.

A few favored holders of land grants from governors of Alta California then controlled, each of them, thousands of acres of land. This acreage was devoted primarily to cattle raising. Most of these fortunate individuals owned town houses in addition to their ranch houses. About the latter life proceeded in simple fashion. The establishments were large, the men giving themselves to their cattle interests, the women to the household. Indians acted as servants. Rodeos and balls gave flavor to living.

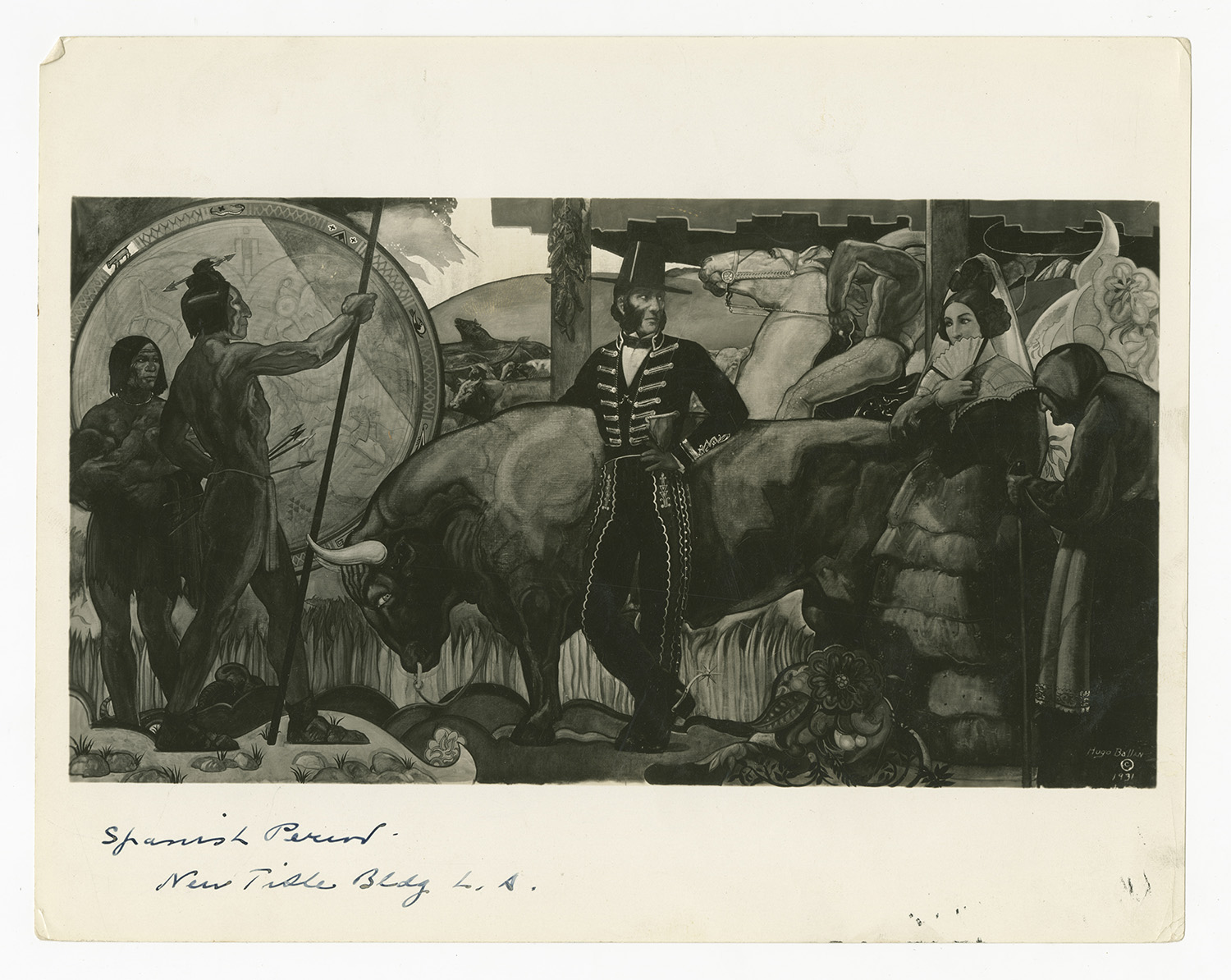

Ballin has caught the full spirit of this pastoral period. In the center there is shown such a man as the celebrated Antonio Maria Lugo might have been. He of the renowned horsemanship and princely estates, in his own vivid setting. The bull is symbolic of the ranchos. To the right, women of the period, dressed after the manner of early Los Angeles. On the left, Indians, the man ready for the hunt, the woman carrying her child. Behind the latter a large disk containing characteristic Indian symbols. In the background a vaquero and his herds. Beyond the hill, the peril of the land: fire.”

In this panel, Ballin offers a romantic portrait of Los Angeles' Spanish and Mexican past, a period in which Southern California's indigenous communities were gradually displaced from their native lands. Although he depicts a scene of the peaceful co-mingling of cultures, the imposition of Spanish authority on the region and development of the ranchos, where "life flowered best" according to Ballin, was often violent, repressive and hotly contested by indigenous peoples. The two native American figures that appear in the panel are strong and noble, but Ballin chooses a wealthy land owner, Antonio Maria Lugo, to be the central character in the spotlight of the piece. He stands confidently to suggest his inherent superiority, and it seems inevitable that he should lead the Indians nearby and the placid scene suggests their willing deference to his authority. A even more pronounced contrast in refinement can be seen between the two female characters in the panel. The woman with the fan is beautiful, light skinned, and virginal, hiding her face behind her fan. She is dressed in elaborate costume that evokes the romance of the Spanish period and illustrate her femininity and class. The servant woman, by contrast, is, hunched and dark skinned, her face hidden, making her almost unrecognizable as a woman.

Ballin thereby represents in this panel what Carey McWilliams described as "the Spanish fantasy past" - a romantic version of the region's history that idealized its Spanish colonial heritage for having brought European civilization to the savage Indians and lamented the state's decline under Mexican rule, thereby positioning the United States as redeemers of Southern California's former glory. In advertisements, tourism campaigns, novels like Helen Hunt Jackson's seminal work Ramona (1884), mission plays, historical pageants and festivals, Anglo residents of Los Angeles reified this "Spanish Fantasy Past," forever changing how Americans understood Los Angeles. Here, Ballin adds his own representation that of that history that is undeniably romantic and fantastic to please his corporate patrons from the Title Guarantee and Trust Company.

One interesting feature of this panel is the vaquero figure Ballin includes in the background of the piece. In skin tone and costuming, Ballin separates this vaquero figure from the Indian characters on the left and the Spanish characters he rises behind, casting him as the only identifiably Mexican figure in the piece. Ballin paints him with physicality and strength that contrasts the elderly servant woman, suggesting that his inclusion was Ballin's way of honoring the contributions of Mexican labor to the region's economy and the city's explosive economic growth at the time. As recent historians have shown, however, Indians performed much of the horse riding and rearing on the ranchos of Southern California and the realities of life in the borderlands often blurred the distinctions between the Indian and Mexican residents. That Ballin chose to construct such a clear racial hierarchy in his representation of "The Spanish Period" - reifying the status quo rather than challenging it - suggests that Ballin may have shared the racial attitudes of his corporate patrons and other Anglo elites in Los Angeles at the time.

Image courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Charles Young Library, University of California Los Angeles.

Appears in the Hugo Ballin Papers, collection number 407, Box 17, Folder 1.

Ballin's quotation appears in his pamphlet, "Murals in the Title Guarantee Building," (Los Angeles: Title Guarantee and Trust Company, 1931).

| Previous page on path | Title Guarantee and Trust Building - Gallery, page 2 of 6 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Title Guarantee and Trust Building - The Spanish Period, 1769-1846"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...