Hollywood Scene Master: Silent Film, Set Design, and Hugo Ballin Productions, Inc. ALTERNATE

by Caroline Luce, PhD

When the Wisconsin State Capitol opened to the public in 1917, Hugo Ballin had ascended to the heights of the Beaux Arts movement in America. He had mounted several small exhibitions, received commissions to paint portraits of wealthy patrons, earned the respect of critics and become the type of American “Master” he hoped to be. But outside of elite art circles, the classical paintings, architecture and sculpture of the Beaux Arts movement was quickly falling out of fashion. A new medium was quickly becoming the most popular form of American culture: film.

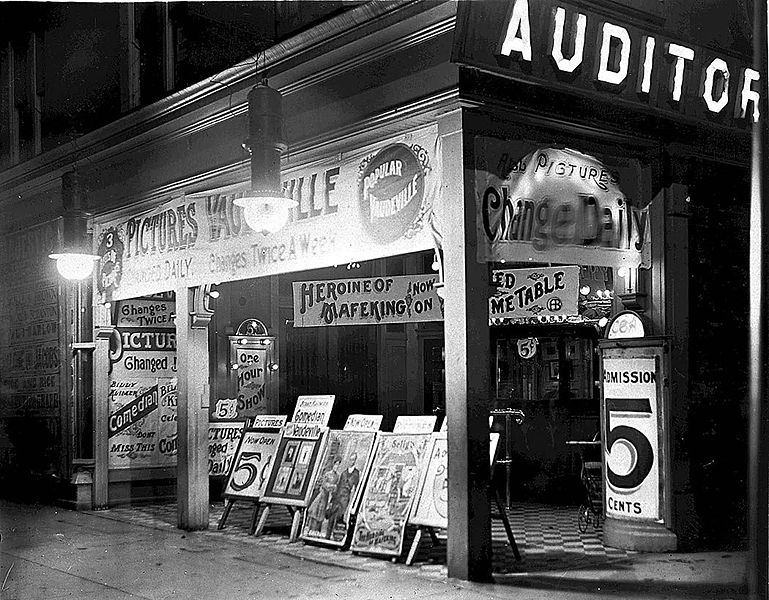

Decades of development in camera technology, recording speed, editing techniques and projection technology reduced the cost of making films and gave rise to a movie boom in the first decade of the 20th century. At first, theater owner projected films alongside burlesque shows, plays and vaudeville acts, but soon theaters devoted solely to showing motion pictures, or “nickelodeons,” began appearing in cities across the country where, for a nickel, viewers could watch multiple short, silent films, usually shown in combination with a live band. The films were ten to fifteen minutes long and included “scenics” (landscapes shot from moving trains), “actualities” (documentary-type shorts often featuring exotic animals), and performances of dances and comedy routines. The low cost of admission made going to the movies a popular form of recreation for working-class and middle-class Americans alike and by 1910, an estimated 26 million Americans visited some 9,000 “nickelodeons” per week. As the audience expanded, production companies soon began making longer, more elaborate, multi-reel motion pictures and theater owners built larger, more opulent venues with more comfortable seating. By the end of the 1910s, the modern film industry was born.1

Soon theater owners began producing films themselves and formed their own filmmaking companies. Many of the nation’s most successful and enduring film studios were established in the 1910s, including Carl Laemmle’s Universal Studios in 1912, Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players Film Company in 1912, which later became Paramount Pictures, William Fox’s Fox Film Corporation in 1915, and both Louis B. Mayer’s Metro Pictures Company and Sam Goldfish’s Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, which would later merge to form MGM. But these new independent producers quickly butted heads with the Edison Trust who asserted its control over the distribution of films by claiming patent rights on all celluloid film and forcing theater owners to pay licensing fees. In 1915, after years of legal wrangling, Federal courts ruled that the Trust was a monopoly and the independent film studios took control of the American film industry. And, by the end of the decade, an increasing number of these emergent studios relocated their production facilities to Los Angeles, shifting the epicenter of the film industry from New York to Hollywood.

As Neal Gabler noted in his seminal book An Empire of Their Own, the studio executives were, “a remarkably homogenous group with similar childhood experiences.” Most had been born to Jewish families in Eastern Europe and raised in poverty before coming to America as young men. Ambitious and entrepreneurial, they sought fortune in sectors of the economy where Jewish immigrants had gained a foothold, some working as salesmen in the garment industry and others finding work in the world of Yiddish theater before breaking into film. Gabler argued their choices to venture into film were motivated by their shared immigrant experiences: although they rejected the language, customs, and religion of their European pasts, they also felt like outsiders, excluded from the traditional elite circles of power in New York and New England. The film industry offered these immigrant entrepreneurs a new business, free of the deeply entrenched hierarchies and social barriers in finance and other professions, where they could escape their pasts and remake themselves as American captains of industry. So too did Los Angeles offer the studio executives a new social, cultural and physical terrain on which they could realize new possibilities for filmmaking, profit making and self-reinvention. In Hollywood, they created “an empire of their own,” both remaking themselves as patriotic and prosperous Americans and remaking America in their mythic, idealized image of it in the process.2

Although the studio executives shared similar life stories, their ideas about film and its role in the American culture varied. Some, like Carl Laemmle and the Warner Brothers, recognized the power of film in working-class, immigrant communities and its potential as a socializing, democratizing force in American society. Laemmle believed film could be a new form of culture, an accessible alternative to the inaccessible “high art” of wealthy elites, or as he put it, “universal entertainment for the universe.” Zukor, Mayer and others, by contrast, believed that films should be a more sophisticated, “higher-class amusement” that would uplift and elevate the public taste. Rather than attempt to capture the gritty realities of modern life, they offered American audiences opulent fantasies - rugged tales of the Western frontier, romantic melodramas, and slapstick comedies – in which beauty and style trumped authenticity. All of the studio executives in Hollywood sought to make movies that would be commercially successful and prioritized profits over artistic innovation. But like their counterparts in the visual arts, they took seriously the impact their films could have in improving American society and, even though they disagreed about how best to do so, sought to contribute to American culture by making art.3

Recognizing film’s potential, Hugo Ballin decided in 1917 that he would stop painting portraits and murals and begin his own foray into the film industry. He was hired by Goldwyn Studios, formed by Broadway producers Edgar and Archibald Selwyn and Sam Goldwyn (nee Goldfish), who had previously partnered with Jesse L. Lasky at Paramount. Although Goldwyn left Paramount because of his dislike for Adolph Zukor, he shared many of Zukor’s attitudes about film and hired Ballin and two other rising stars of the Beaux Arts scene, Arthur Hopkins and Everett Shinn, to elevate and refine the art direction of his films. The position allowed Ballin to apply his classical training and storytelling techniques in new ways.

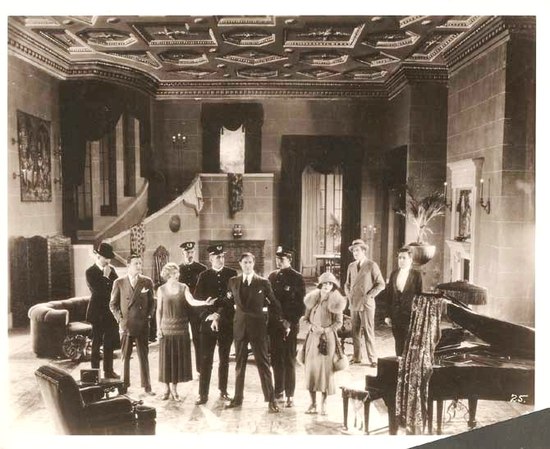

Because of the technical limitations of filmmaking in the silent film era, Ballin and other art directors had a significant role to play in adding complexity to the films they worked on. Cameras were fixed in the early days, offering viewers static shots in a single frame and art directors like Ballin needed to create sets that remedied the flattening effect by adding depth and texture to the scenes. Since Ballin could not rely on using color as he had in his paintings, he added otherwise unnecessary objects and furnishings to his sets and exaggerated decorative features like door moldings and columns, using the adornments to create contrasts of dark and light. Like his peers, Ballin also designed sets with multiple volumes to create “broken planes, with receding and advancing surfaces, each receiving a different amount of light” that would give the shots dimension. In his set for “Money Mad” (1918), for example, Ballin added oversized drapes to the windows, an embellished ceiling, and a winding staircase lined by columns leading to a small porch. As historian Merry Ovnick has shown, set like those designed by Ballin and other art directors of the silent film era created a new “visual code” that helped to convey the drama and meaning of films, and in doing so, advanced a new set of decorative motifs recognizable to American film audiences.4

Ballin’s approach to filmmaking mirrored his ideals about visual art. He argued that the set designer’s function was “to erect beauty and reality in our settings” that would elevate the quality of the film as a whole. But in describing his work as an art director, Ballin also expressed a new, populist attitude about who art should be made for:

Ballin, who had once dismissed the idea that artists should attempt to reach broad audience and believed he and other “Master” artists to be the arbiters of taste, now sought to bring that art to “the great masses of people.” His comments suggest that his embrace of film as a medium for art was part of an evolution in his ideals as an artist.

Ballin worked on over two dozen films as an Art Director for Goldwyn Studios and another dozen as a Production Designer and Director before he, like so many others, left New York and relocated to Los Angeles. Shortly after his arrival, he parted ways with Goldwyn Pictures and formed his own company, Hugo Ballin Productions Inc. He described his decision to leave as part of his desire to make a “more subtle and refined” style of film. The problem with American filmmakers, he argued, was their preoccupation with “the mere novelty of motion,” which left American audiences thirsting for films with a “more spiritual kind of acting…more innuendo and intimation.” The filmmaker, like the painter, should instead create more refined pictures that offered “pure decorative beauty” that would “fall upon the hearts [of the audience] like ‘a gentle rain from heaven.’” By forming his own production company, Ballin could capitalize on the populist potential of film and bring the refined, classicism he so admired to an expanded audience, allowing him reach new heights of personal success while enriching and improving American society in the process.6

Like his paintings, Ballin’s films often retold timeless stories and featured beautiful, virginal female leads, played almost exclusively by his wife, Mabel. He based his first film as an independent producer, Pagan Love (1920), on the popular novel The Honorable Gentleman by Achmed Abdullah in which an Irish-Jewish immigrant girl falls in love with a Chinese student, using sets of “uncommon beauty and simplicity” to offer his audience a “fragment, delicate fantasy.” His second film, East Lynne (1920), was also “a modernized version of a classic story” featuring his wife Mabel as a woman who leaves her husband and young children after being seduced by a wealthy cad only to return penniless, forced to work in her former husband’s home in disguise. Ballin was so confident in his storytelling ability that he made East Lynne without including written captions to advance the plot, using only his vivid visuals to tell the allegorical tale of a woman’s fall from grace.7Ballin also avoided using subtitles and intertitle captions in his film The Journey’s End (1921) the following year.

For a full list of Ballin’s films… http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0050846/

Unfortunately for Ballin, none of his movies achieved the critical acclaim or commercial success of those of other studio owners and his production company folded in 1925. He had, however, made a place for himself in the social milieu of Jewish filmmakers in Hollywood during his film career and through their patronage, returned to painting after his production company failed. As part of their quest to assimilate and ascend into the American elite, the foreign-born Jewish film executives used their tremendous earnings to reinvent themselves as men of refinement and culture.8 They spent lavishly on palatial mansions complete with stables and tennis courts, built country clubs and beach cabanas, and hosted spectacular parties with the finest spirits and cuisine. Ballin’s extensive training and bona fides as a set designer made him a preferred choice to decorate the homes of Hollywood’s moguls, and in the late 1920s, he had secured his first mural commissions in Los Angeles. In 1926, he was hired to decorate the home of Milton Getz, president of Union Bank and Trust, and, in 1929, the Warner Brothers hired him to create murals in the interior of the new Wilshire Boulevard Temple. The Temple was erected by the city’s oldest Jewish congregation, Cong. B’nai B’rith, to house their ever-growing membership, which included the Warner family and dozens of other prominent Hollywood players. Ballin’s murals at Wilshire Boulevard Temple thereby secured his place within the Jewish milieu in Hollywood and helped to kick start his mural painting career in Los Angeles.

UCLA Special Collections |

Nickelodeon c. 1910, WikiMedia Commons |

Goldwyn's Mascot, Leo the Lion (1917-1924), WikiMedia Commons |

Sam Goldwyn (Goldfish), WikiMedia Commons |

Although the studio executives shared similar life stories, their ideas about film and its role in the American culture varied. Some, like Carl Laemmle and the Warner Brothers, recognized the power of film in working-class, immigrant communities and its potential as a socializing, democratizing force in American society. Laemmle believed film could be a new form of culture, an accessible alternative to the inaccessible “high art” of wealthy elites, or as he put it, “universal entertainment for the universe.” Zukor, Mayer and others, by contrast, believed that films should be a more sophisticated, “higher-class amusement” that would uplift and elevate the public taste. Rather than attempt to capture the gritty realities of modern life, they offered American audiences opulent fantasies - rugged tales of the Western frontier, romantic melodramas, and slapstick comedies – in which beauty and style trumped authenticity. All of the studio executives in Hollywood sought to make movies that would be commercially successful and prioritized profits over artistic innovation. But like their counterparts in the visual arts, they took seriously the impact their films could have in improving American society and, even though they disagreed about how best to do so, sought to contribute to American culture by making art.3

Mad Money (1918), Goldwyn Studios, LA Weekly |

Recognizing film’s potential, Hugo Ballin decided in 1917 that he would stop painting portraits and murals and begin his own foray into the film industry. He was hired by Goldwyn Studios, formed by Broadway producers Edgar and Archibald Selwyn and Sam Goldwyn (nee Goldfish), who had previously partnered with Jesse L. Lasky at Paramount. Although Goldwyn left Paramount because of his dislike for Adolph Zukor, he shared many of Zukor’s attitudes about film and hired Ballin and two other rising stars of the Beaux Arts scene, Arthur Hopkins and Everett Shinn, to elevate and refine the art direction of his films. The position allowed Ballin to apply his classical training and storytelling techniques in new ways.

The World and Its Woman (1919), Goldwyn, WikiMedia Commons |

Because of the technical limitations of filmmaking in the silent film era, Ballin and other art directors had a significant role to play in adding complexity to the films they worked on. Cameras were fixed in the early days, offering viewers static shots in a single frame and art directors like Ballin needed to create sets that remedied the flattening effect by adding depth and texture to the scenes. Since Ballin could not rely on using color as he had in his paintings, he added otherwise unnecessary objects and furnishings to his sets and exaggerated decorative features like door moldings and columns, using the adornments to create contrasts of dark and light. Like his peers, Ballin also designed sets with multiple volumes to create “broken planes, with receding and advancing surfaces, each receiving a different amount of light” that would give the shots dimension. In his set for “Money Mad” (1918), for example, Ballin added oversized drapes to the windows, an embellished ceiling, and a winding staircase lined by columns leading to a small porch. As historian Merry Ovnick has shown, set like those designed by Ballin and other art directors of the silent film era created a new “visual code” that helped to convey the drama and meaning of films, and in doing so, advanced a new set of decorative motifs recognizable to American film audiences.4

Help Yourself (1920) Goldwyn, WikiMedia Commons |

Pagan Love (1920) Hugo Ballin productions, UCLA Special Collections |

Ballin’s approach to filmmaking mirrored his ideals about visual art. He argued that the set designer’s function was “to erect beauty and reality in our settings” that would elevate the quality of the film as a whole. But in describing his work as an art director, Ballin also expressed a new, populist attitude about who art should be made for:

“I have from the beginning taken the motion picture as a serious medium for artistic expression. Since the days of the minstrels who went about in ancient lands chanting the glories of bygone days and heroic exploits, there has been no medium to which the great masses of people have had an opportunity to respond. This new thing, this original medium, is not limited as the ‘legitimate’ theatre is.”5

Ballin, who had once dismissed the idea that artists should attempt to reach broad audience and believed he and other “Master” artists to be the arbiters of taste, now sought to bring that art to “the great masses of people.” His comments suggest that his embrace of film as a medium for art was part of an evolution in his ideals as an artist.

Ballin worked on over two dozen films as an Art Director for Goldwyn Studios and another dozen as a Production Designer and Director before he, like so many others, left New York and relocated to Los Angeles. Shortly after his arrival, he parted ways with Goldwyn Pictures and formed his own company, Hugo Ballin Productions Inc. He described his decision to leave as part of his desire to make a “more subtle and refined” style of film. The problem with American filmmakers, he argued, was their preoccupation with “the mere novelty of motion,” which left American audiences thirsting for films with a “more spiritual kind of acting…more innuendo and intimation.” The filmmaker, like the painter, should instead create more refined pictures that offered “pure decorative beauty” that would “fall upon the hearts [of the audience] like ‘a gentle rain from heaven.’” By forming his own production company, Ballin could capitalize on the populist potential of film and bring the refined, classicism he so admired to an expanded audience, allowing him reach new heights of personal success while enriching and improving American society in the process.6

East Lynne (1920), Hugo Ballin Productions, UCLA Special Collections |

Like his paintings, Ballin’s films often retold timeless stories and featured beautiful, virginal female leads, played almost exclusively by his wife, Mabel. He based his first film as an independent producer, Pagan Love (1920), on the popular novel The Honorable Gentleman by Achmed Abdullah in which an Irish-Jewish immigrant girl falls in love with a Chinese student, using sets of “uncommon beauty and simplicity” to offer his audience a “fragment, delicate fantasy.” His second film, East Lynne (1920), was also “a modernized version of a classic story” featuring his wife Mabel as a woman who leaves her husband and young children after being seduced by a wealthy cad only to return penniless, forced to work in her former husband’s home in disguise. Ballin was so confident in his storytelling ability that he made East Lynne without including written captions to advance the plot, using only his vivid visuals to tell the allegorical tale of a woman’s fall from grace.7Ballin also avoided using subtitles and intertitle captions in his film The Journey’s End (1921) the following year.

The Journeys End (1920), UCLA Special Collections |

For a full list of Ballin’s films… http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0050846/

Unfortunately for Ballin, none of his movies achieved the critical acclaim or commercial success of those of other studio owners and his production company folded in 1925. He had, however, made a place for himself in the social milieu of Jewish filmmakers in Hollywood during his film career and through their patronage, returned to painting after his production company failed. As part of their quest to assimilate and ascend into the American elite, the foreign-born Jewish film executives used their tremendous earnings to reinvent themselves as men of refinement and culture.8 They spent lavishly on palatial mansions complete with stables and tennis courts, built country clubs and beach cabanas, and hosted spectacular parties with the finest spirits and cuisine. Ballin’s extensive training and bona fides as a set designer made him a preferred choice to decorate the homes of Hollywood’s moguls, and in the late 1920s, he had secured his first mural commissions in Los Angeles. In 1926, he was hired to decorate the home of Milton Getz, president of Union Bank and Trust, and, in 1929, the Warner Brothers hired him to create murals in the interior of the new Wilshire Boulevard Temple. The Temple was erected by the city’s oldest Jewish congregation, Cong. B’nai B’rith, to house their ever-growing membership, which included the Warner family and dozens of other prominent Hollywood players. Ballin’s murals at Wilshire Boulevard Temple thereby secured his place within the Jewish milieu in Hollywood and helped to kick start his mural painting career in Los Angeles.

Discussion of "Hollywood Scene Master: Silent Film, Set Design, and Hugo Ballin Productions, Inc. ALTERNATE"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...